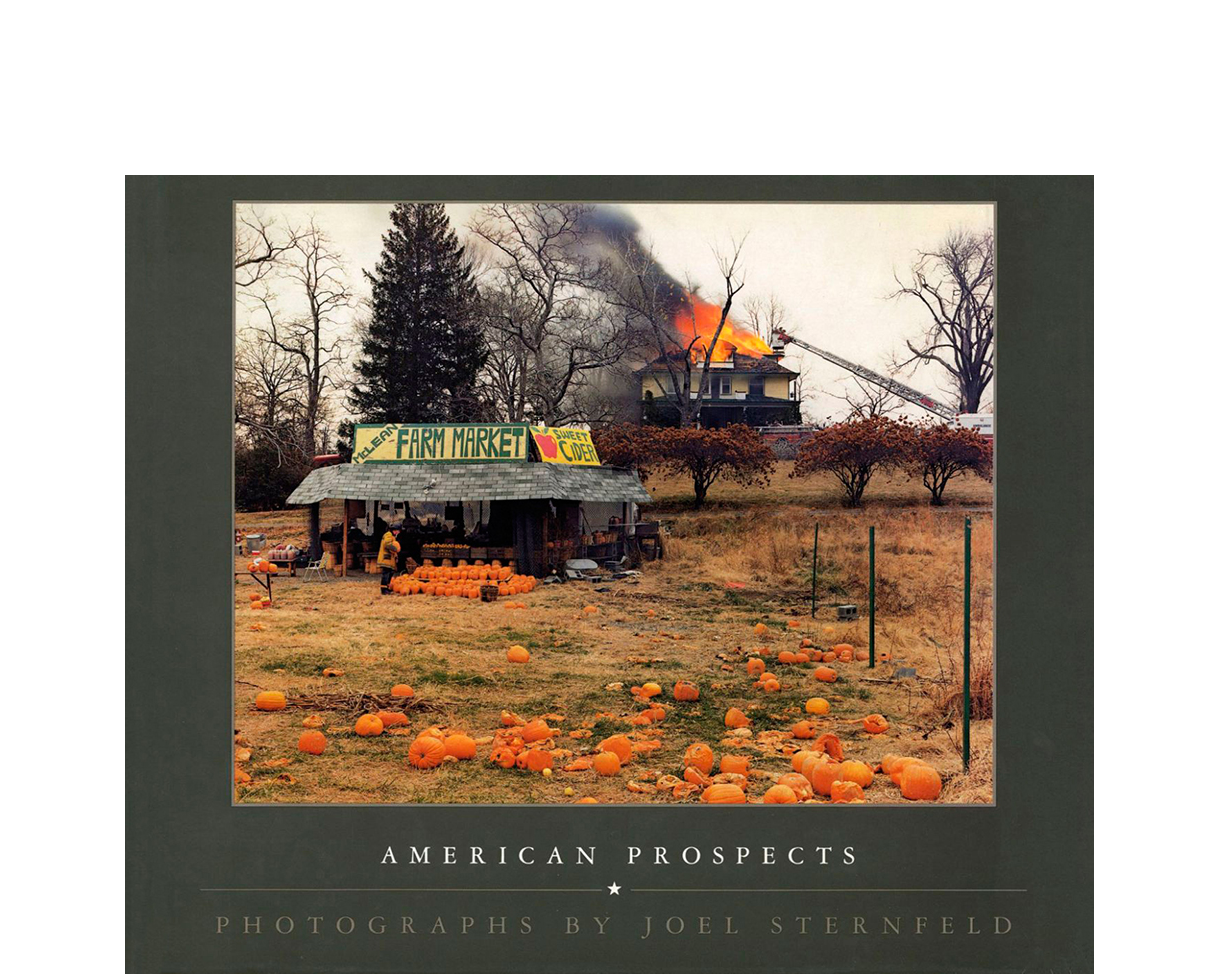

Joel Sternfeld on Robert Adams

Essay from Book Photographers Looking At Photographs - ISBN: 978-1-59711-006-8

Important bodies of work have come along in photography at times of great disruption in society. In moments of large-scale social transformation, an artist has arisen to record that which they held precious, that which would be no more. Photography’s essential ability—to catch time, to hold it in its place—is used to do exactly that.

Think of Atget going forth, lumbering with his heavy equipment on an early Sunday morning to record the small corners of “old Paris” that remained despite Haussmann’s campaign to build the militarily efficient wide boulevards of modern Paris.

Or consider Sander, who singlehandedly rebuilt German society with his archive of essential types following the ravages of the Great War.

With architectural and social perspicuity, Walker Evans recorded the eastern tier of the United States as the Great Depression brought its hardships. For William Eggleston, the impulse seems to have been to record the shards of an older attitude toward life in the South, just as the interstates, restaurant and motel chains spread across the region.

In Germany in the 1960s, Bernd and Hilla Becher catalogued utilitarian buildings of the early industrial age that were unlikely to be considered worthy of historic preservation, just as the technological revolution was beginning to overwhelm the world.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Nan Goldin created an album of friends and lovers, just as the AIDS crisis was ravaging her family.

The work of Robert Adams might fit within this thesis—and it might not. At a time when the Vietnam War was tearing apart the nation’s psyche, American cities were burning in racial strife, Nixon was being impeached, and the landscape everywhere was being covered in less than exalted development, a white house, on a sweet summer night, might have represented an effort to reference a mythologized American past.

Then again, the shadows on the house in this picture are quite dark and possibly ominous. Nor does Adams limit his vision to summer nights or small churches of the prairie. Imbued with a Whitmanesque consciousness, he opens his eyes to everything that is occurring—the poorly built homes, the strip malls that defy community, the littered embankments of the charmless interstates. His pictures remain beautiful and suddenly, shockingly, become more so. This is the pure mystery of Adam’s work: the visual embrace of all that he hates, the ineluctable beauty that he finds.

Some, including Adams, have speculated that it may be the light of the high plains infusing all that it touches with grace.

Others have wondered if it is the exquisite black-and-white graphical order of his pictures that accounts for their transcendent quality.

Or perhaps it’s something else entirely: Beauty, it has been said, walks along the edge of opposites. In the work of Robert Adams, we see the quietude of the plains and we see the exalted Rockies. In the same frame is all of the mundane stuff of our civilization, such as it is.

These elements co-exist in a kind of poetic equipoise, angry and full of love.