Sternfeld Captures Contemporary America’s Ambiguity

A review from the Chicago Tribune by Larry Thall

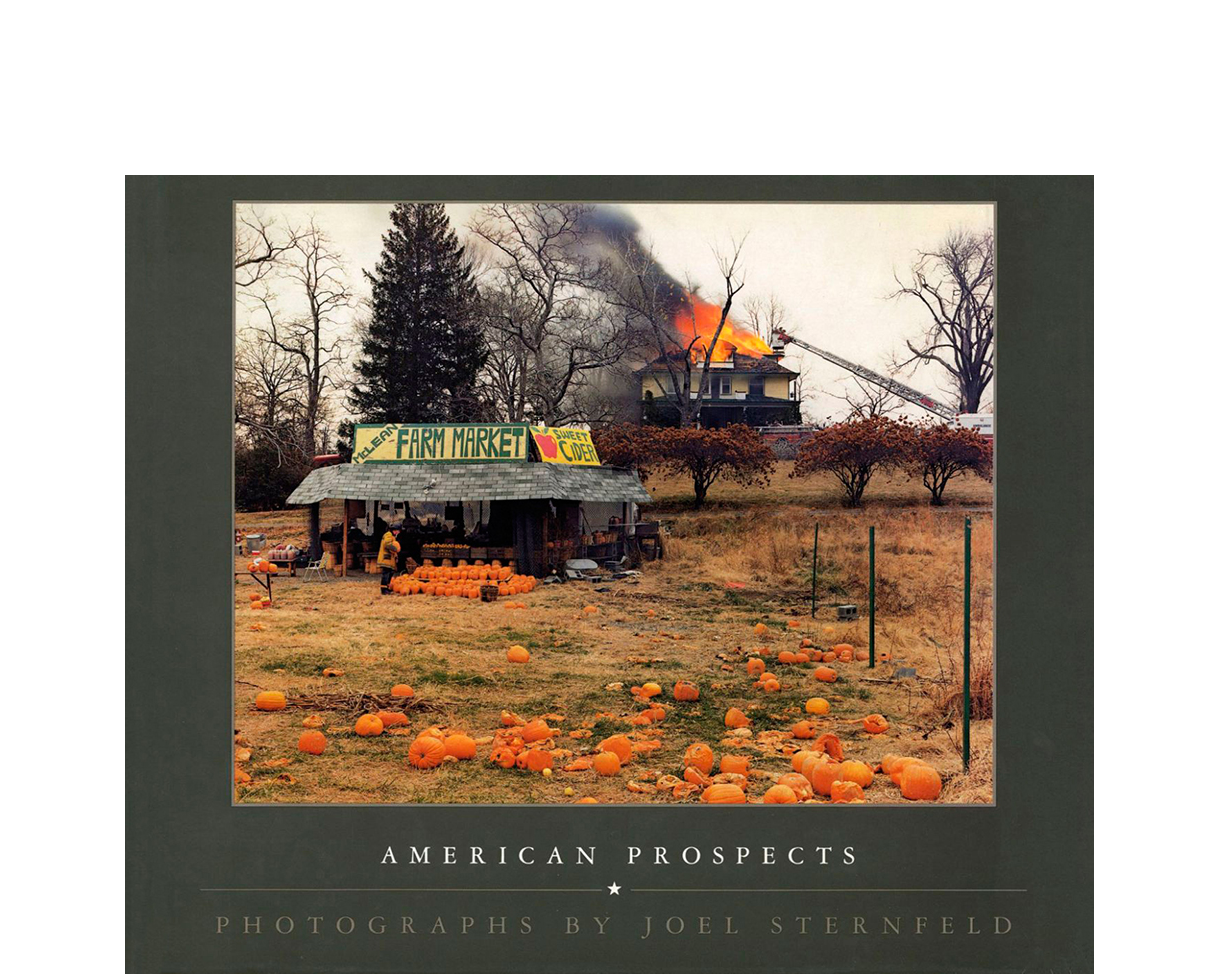

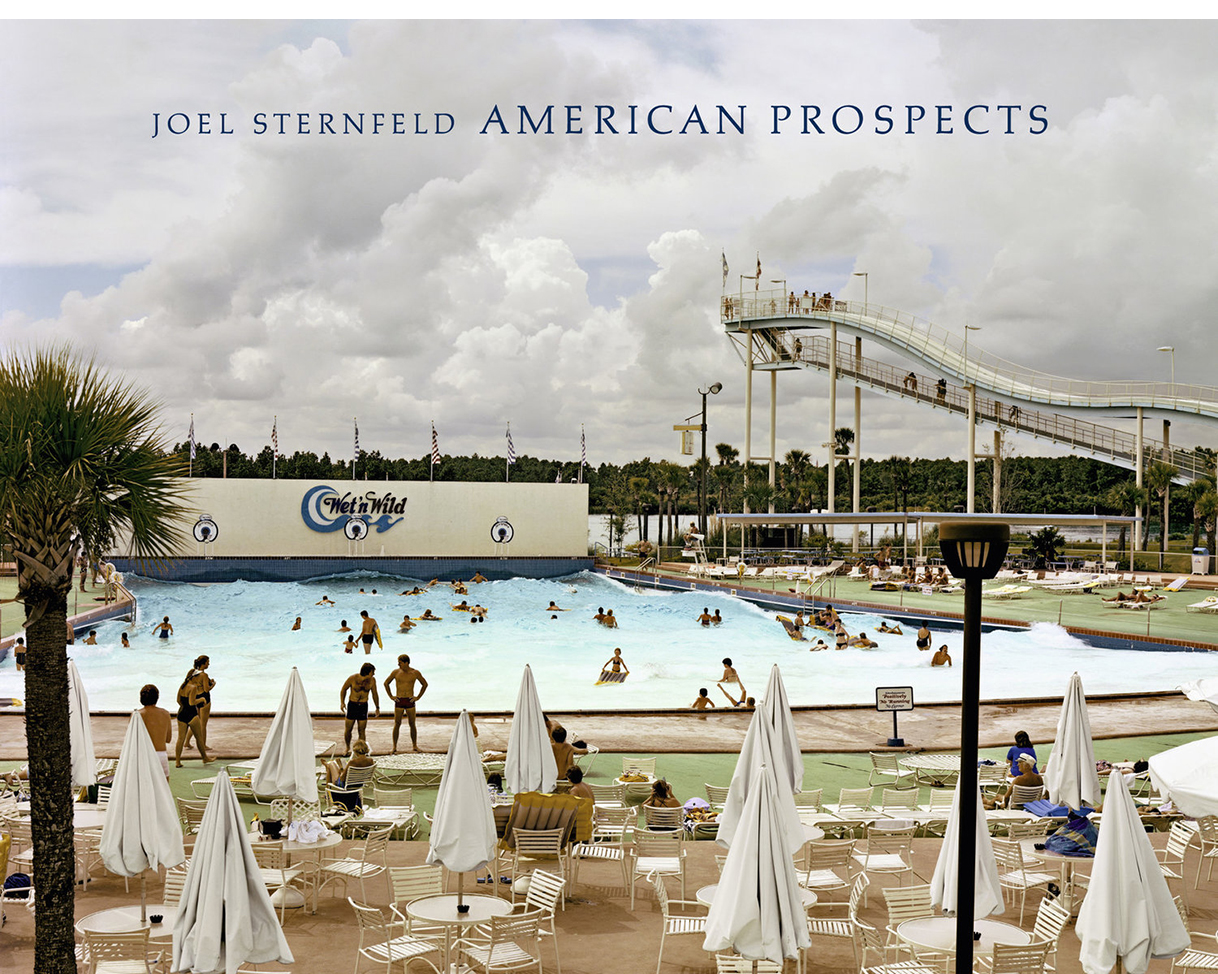

Nero fiddled (actually he lyred) while Rome burned. In one of Joel Sternfeld`s best-known photographs, a firefighter casually selects a pumpkin from a roadside produce stand while in the background a roaring house fire he`d been summoned to extinguish continues to rage.

As with Nero, the firefighter`s apparent ambivalence to impending disaster seems shocking. So much so, in fact, that viewers might be tempted to question the veracity of their initial assumptions. Is the fire so far out of control that the commander has decided to let it burn itself out? Could the firefighter in question possibly have been sent down the hill to collect himself, after inhaling a bit too much smoke?

Once viewers permit themselves the slightest doubt as to whether the firefighter is, in fact, derelict in his duties, the photograph becomes imbued with ambiguity.

That`s what makes it the perfect image for the dust jacket of Sternfeld`s monograph ``American Prospects`` (Times Books, 1987). Just as it would seem appropriate to place a question mark after the book`s open-ended-perhaps hopeful, perhaps gloomy-title, so too with many of the photographer`s images. Critic Sally Eauclaire, writing about Sternfeld in her book ``New Color/

New Work`` (Abbeville Press, 1984), says, ``He would agree with John Updike that `Everything unambiguously expressed seems somehow crass to me ... My work says, ``Yes, but.`````

The exhibition ``Joel Sternfeld`` goes on view Saturday at the Art Institute of Chicago. The show`s 17 color photographs were selected from a recent 50-image gift to the museum. All the pictures come from Sternfeld`s mammoth ``American Prospects`` series, which he worked on for eight years. However, almost half the images in the show aren`t published in the book. So a few should seem fresh, even to longtime Sternfeld fans.

Born in 1944, the New York-based photographer began crisscrossing the country with his 8-by-10-inch wooden view camera in 1978, traveling in stretches ranging from a week to a year, in his Volkswagen camper. His treks have taken him through most of the lower 48 states, as well as Alaska in 1984 (for the state`s 25th anniversary). All told, Sternfeld says, he photographed approximately 1,200 scenes.

The house fire represents a local, personal catastrophe. However, the photographer also addresses such societal anxieties as urban sprawl and other environmental blunders. Again, the pictures feature ambiguity and, in some cases, humor, thus combining to keep Sternfeld from being stereotyped as a crusader with a camera, and placing him more appropriately in the role of an objective observer of the contemporary American scene.

During the early `80s, Sternfeld made many pictures in northern Arizona and southern Utah near the Glen Canyon Dam (probably the hydroelectric dam most hated by conservationists) and the manmade, 180-mile-long water-storage reservoir created by it known as Lake Powell.

In ``Lake Powell, Arizona, August 1982,`` Sternfeld completely filled the center of his camera`s viewfinder with a large mound of soil and stone, whose unnatural-looking formation suggests it was the creation of a bulldozer. Only a small section of lake is visible at each side of the pile. In the background three dramatic lightning bolts descend from the sky to the rim of the reservoir, as if to say, ``Let`s generate some kilowatts the natural way!``

An even more comic environmentally oriented shot (found in the book, but unfortunately absent from the exhibition) shows a middle-age couple standing behind their gas-powered mower, amid a large expanse of lush, green lawn. Both are wearing surgical-type masks.

Given the apparent health of the grass and the trees in the background, one is forced to conclude they are trying to protect themselves from synthetic chemical pesticides and herbicides. Only the photo`s title, ``After an Eruption of Mount St. Helens, Vancouver, Washington, June 1980,`` gives the game away.

Like photographer Robert Adams, Sternfeld has expended much energy documenting the intrusion of suburban-type housing developments in the West`s arid landscape.

Adams, who shoots in black and white, tends to make his images while construction is still in progress, before lawns are in place, and while various building materials remain strewn about. The incongruity of such scenes, surrounded as many are by pristine desert landscapes, leaves little doubt in the viewer`s mind as to how Adams feels about such developments.

Photographing in color, Sternfeld`s opinions are less clear. In

``Pendleton, Oregon, June 1980,`` he shows a small, completed housing development whose uniformly brown dwellings look quite at home, nestled as they are, among gently rolling hills of somber earth tones.