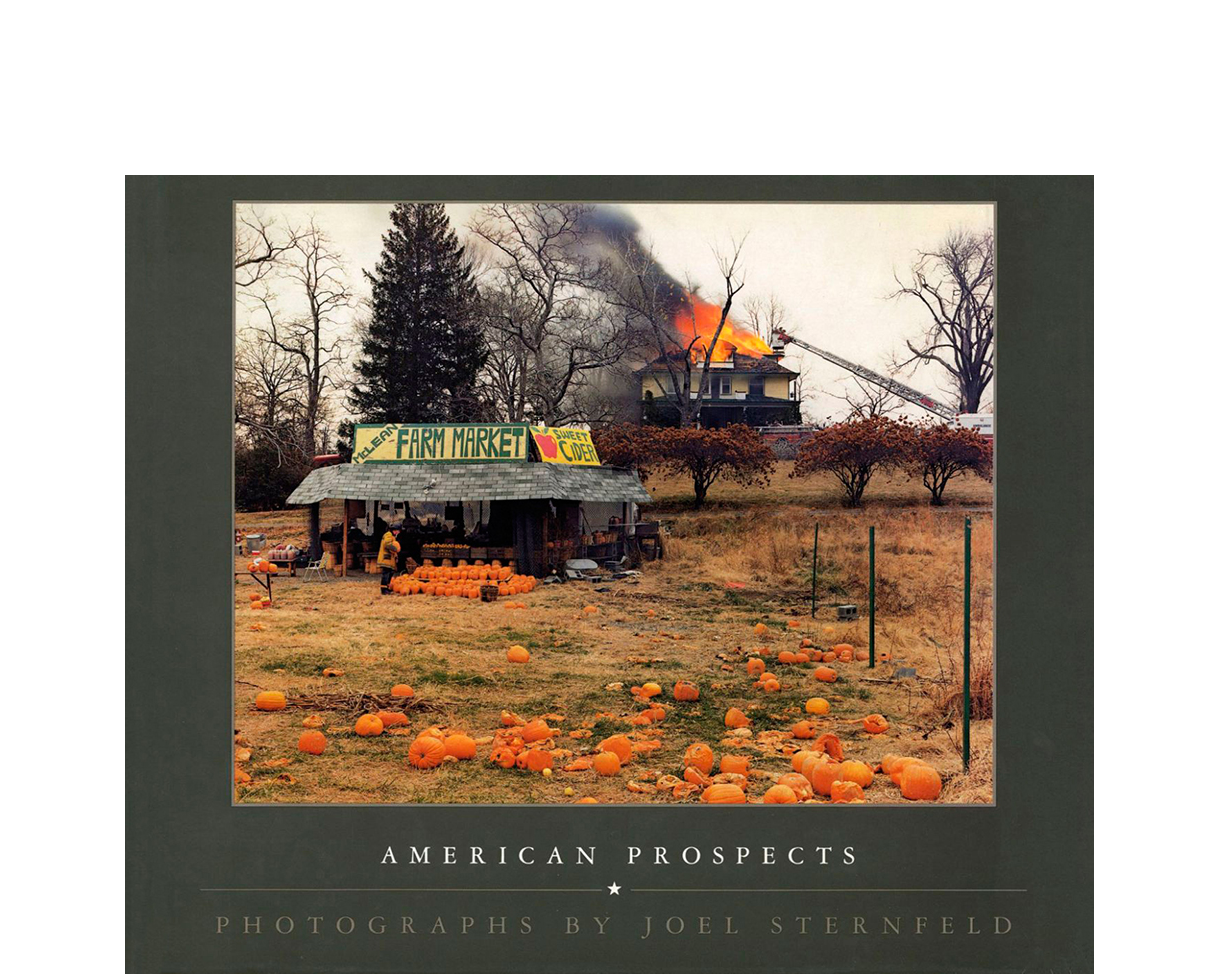

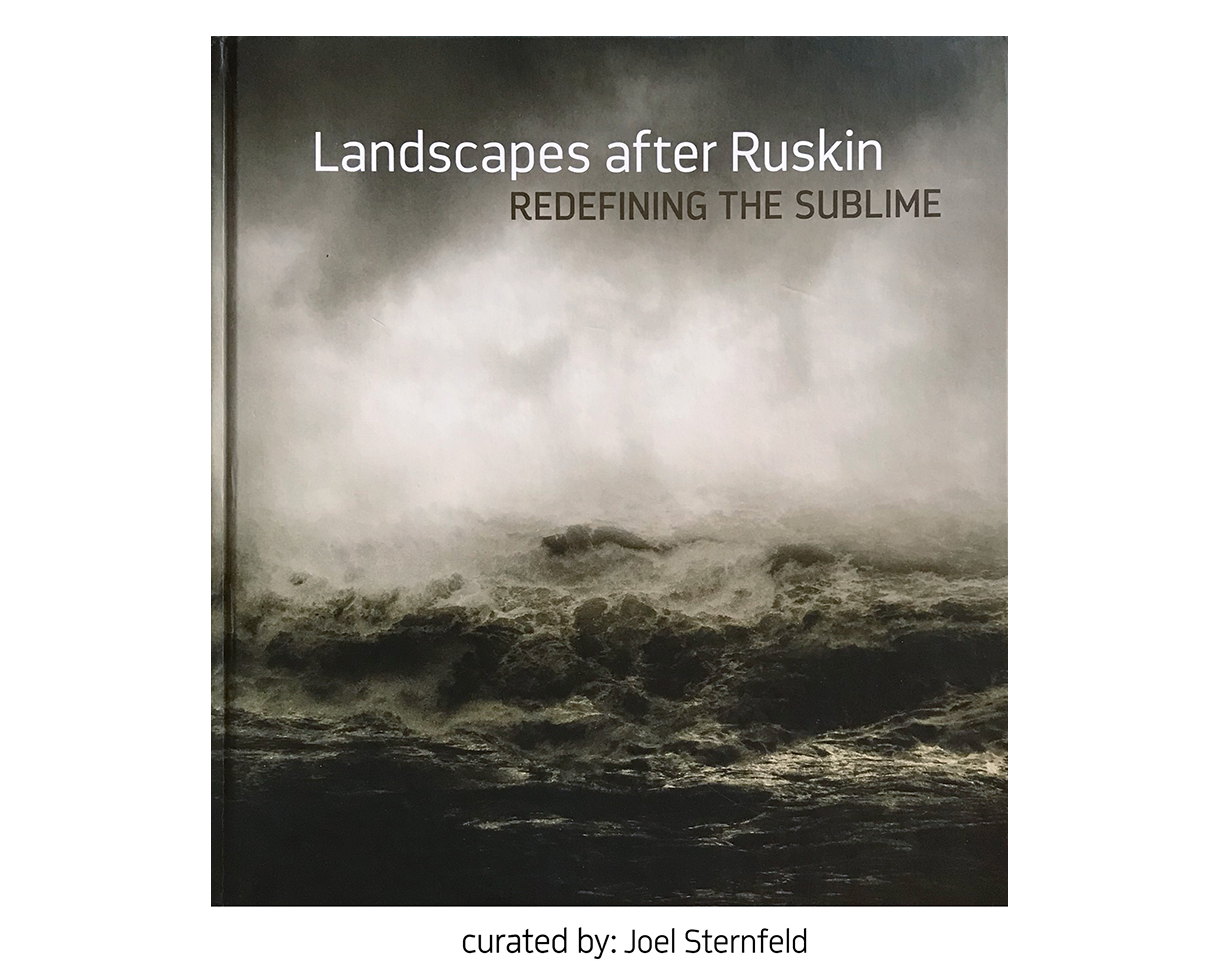

The Calamitous Sublime

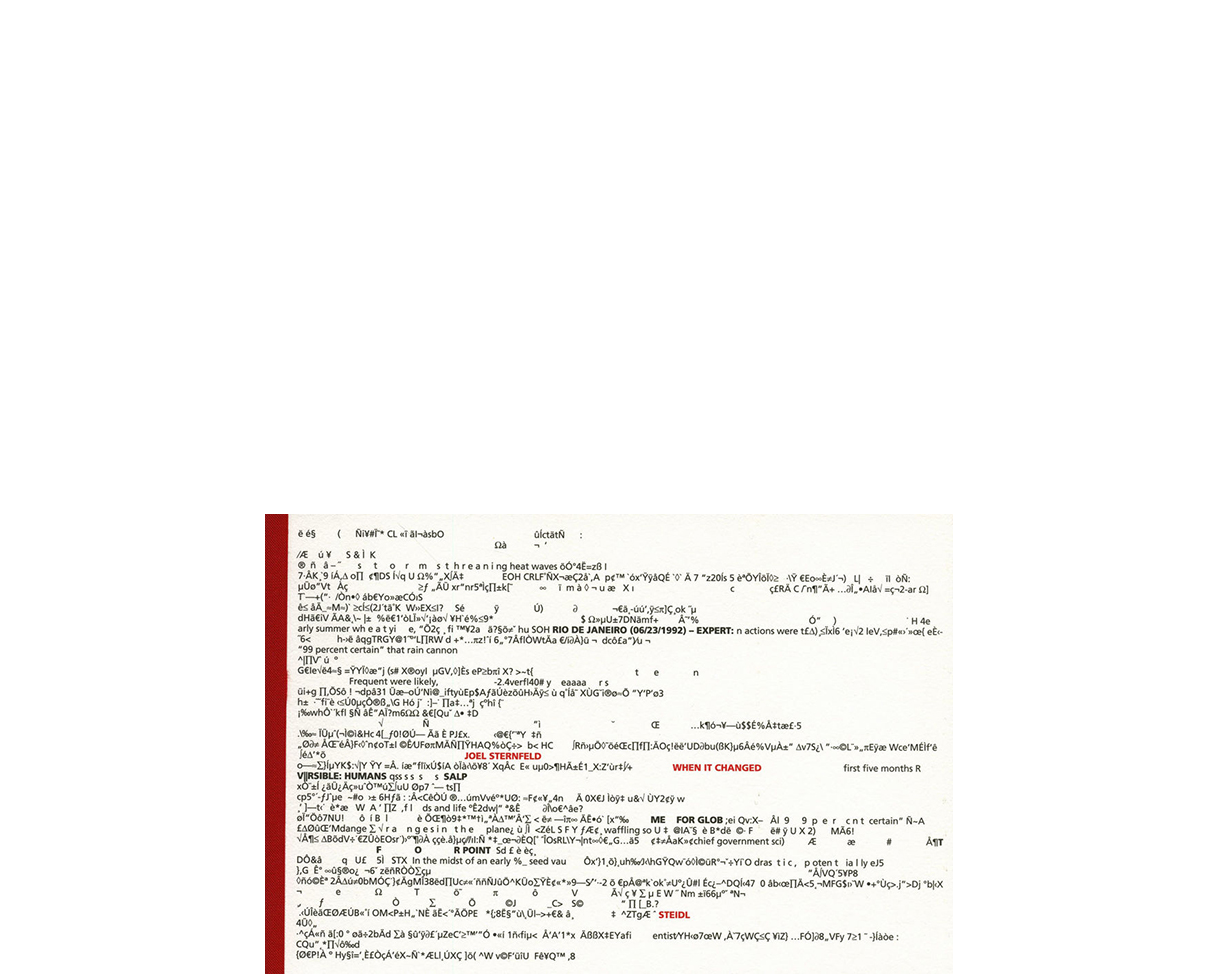

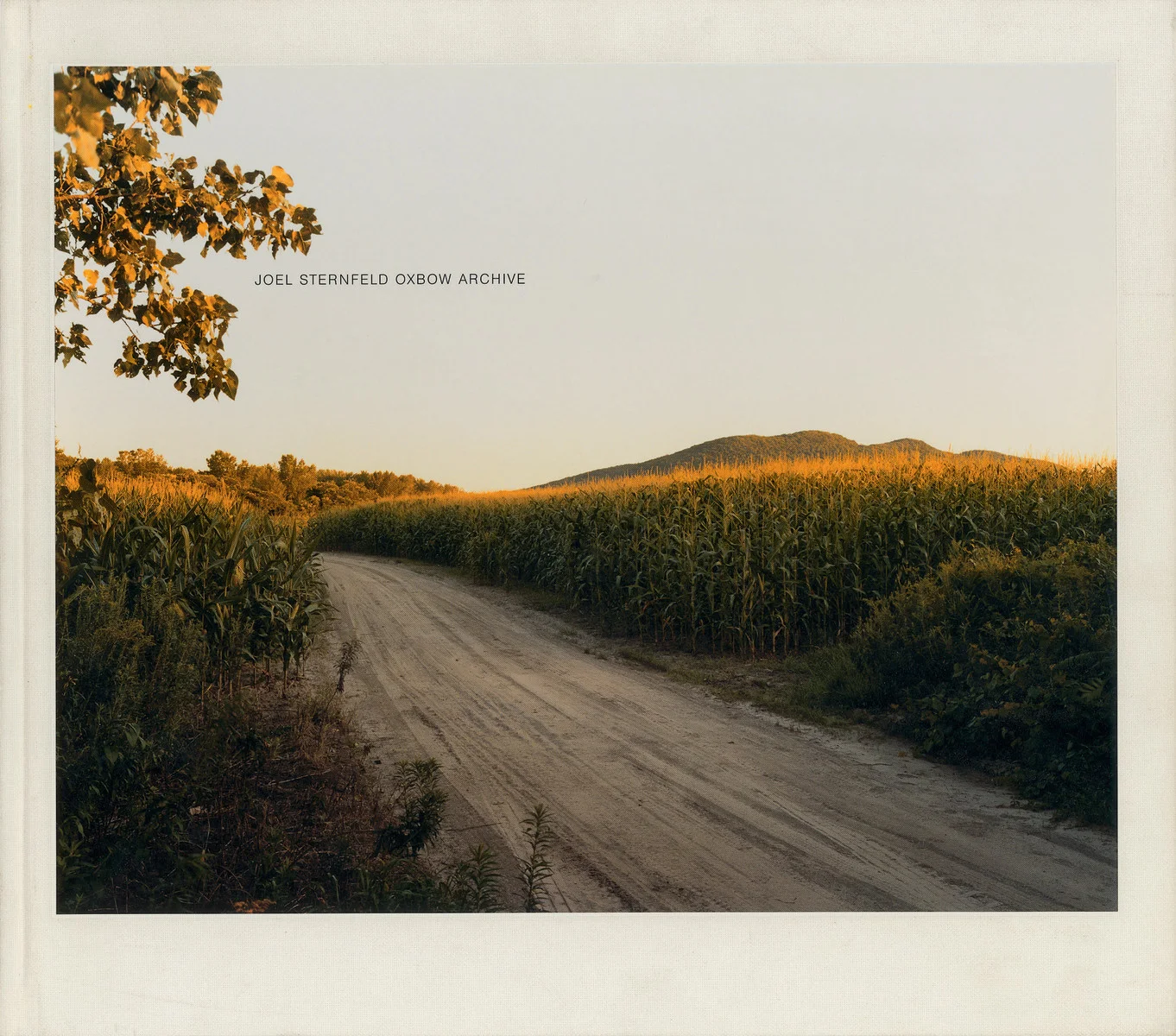

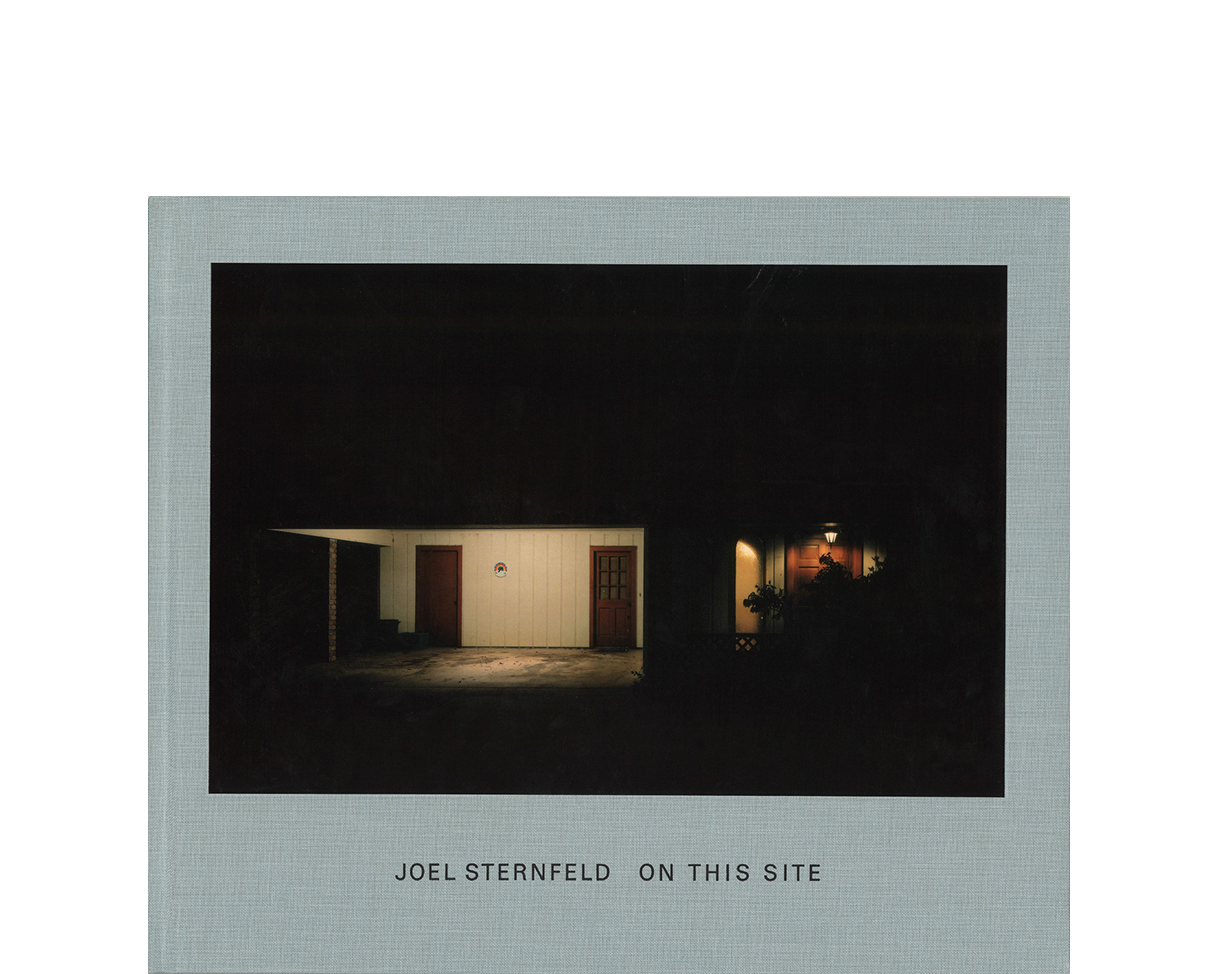

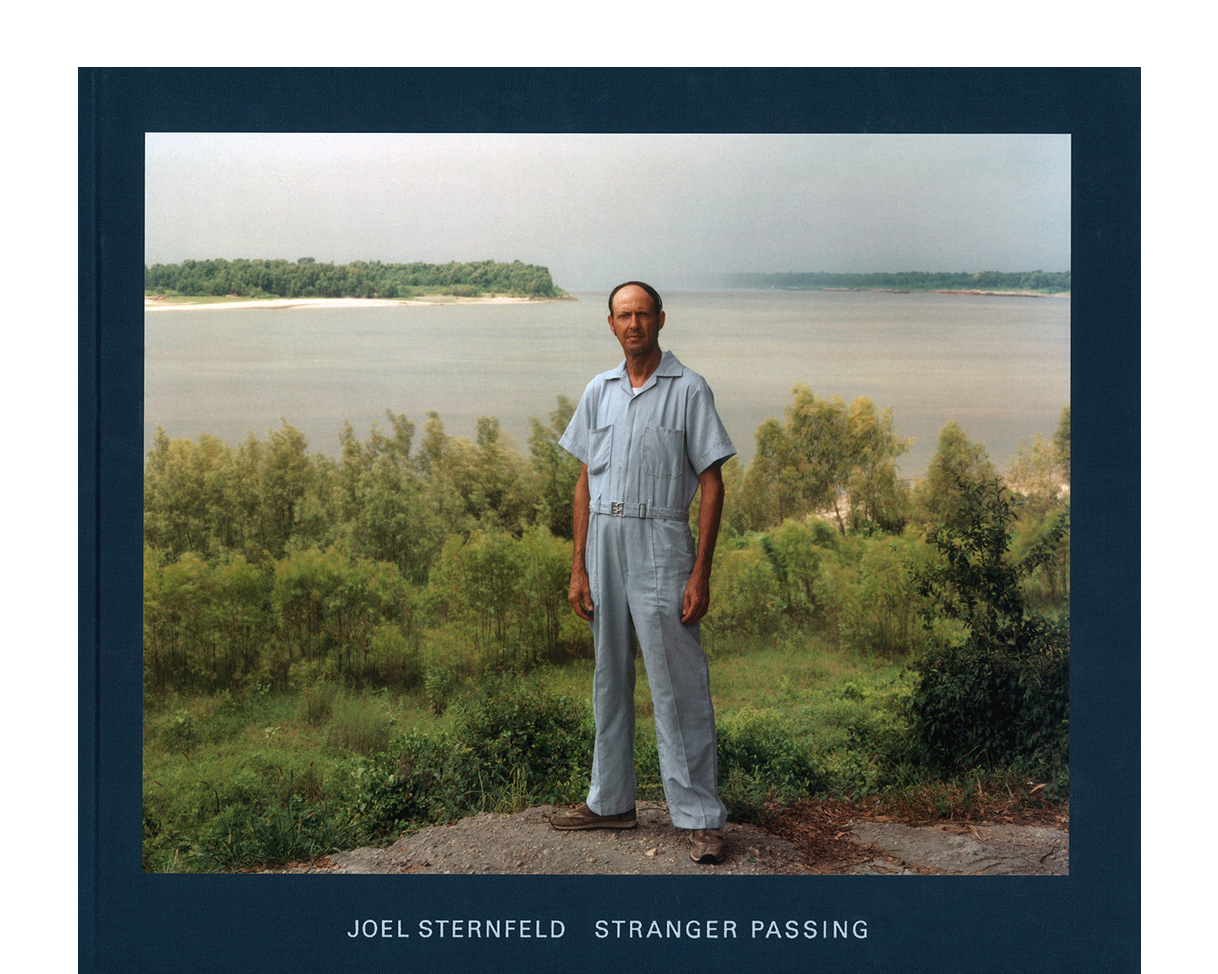

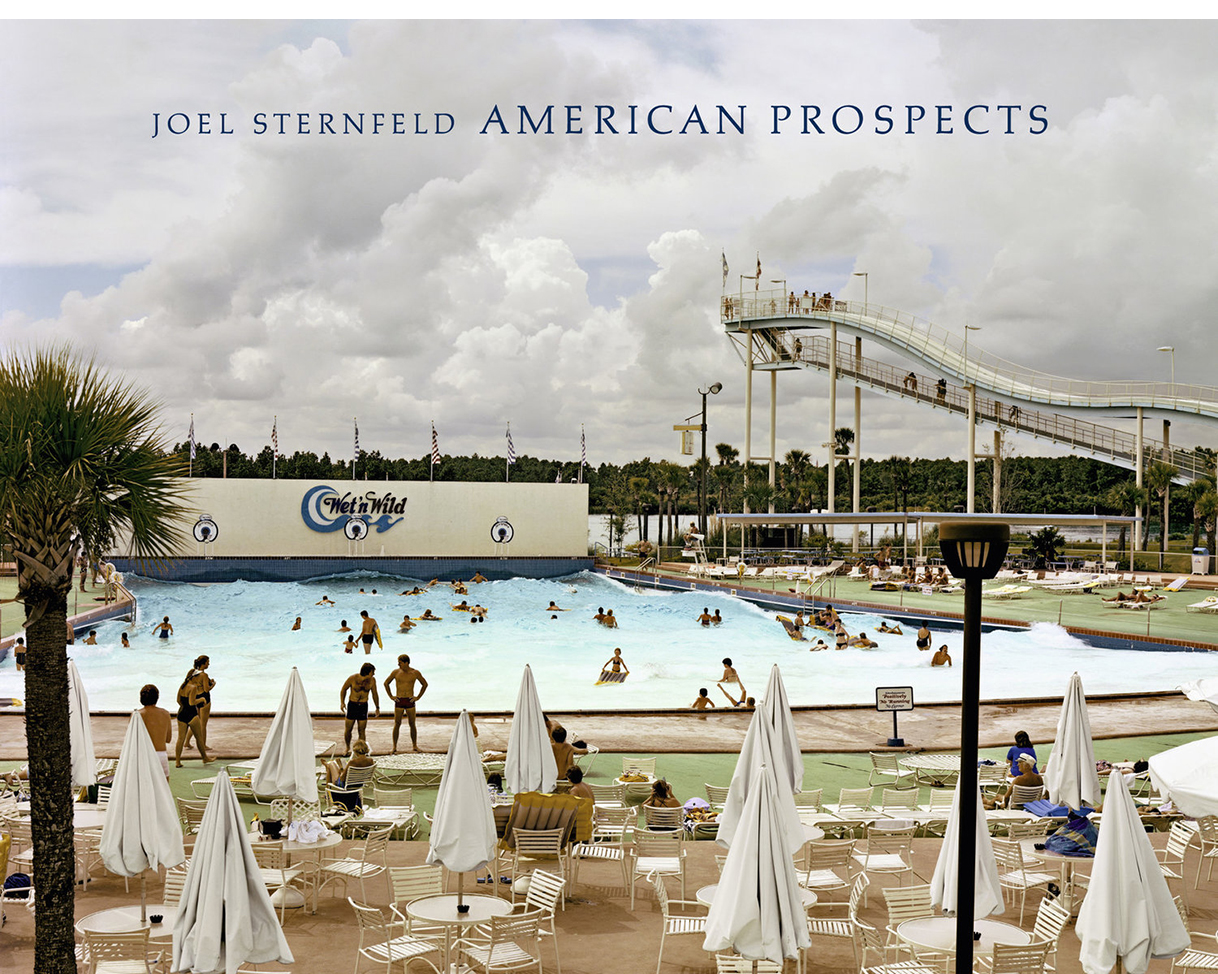

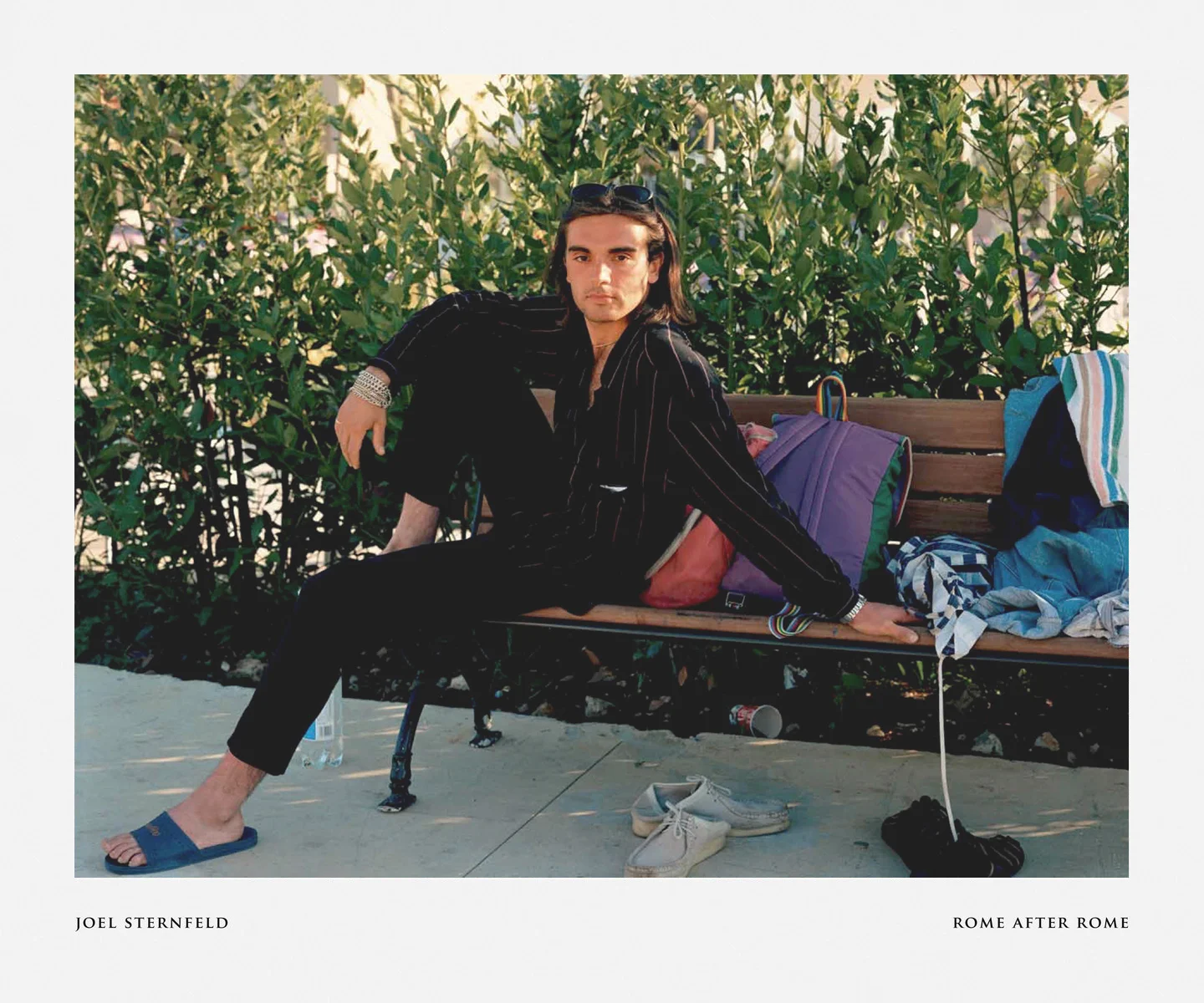

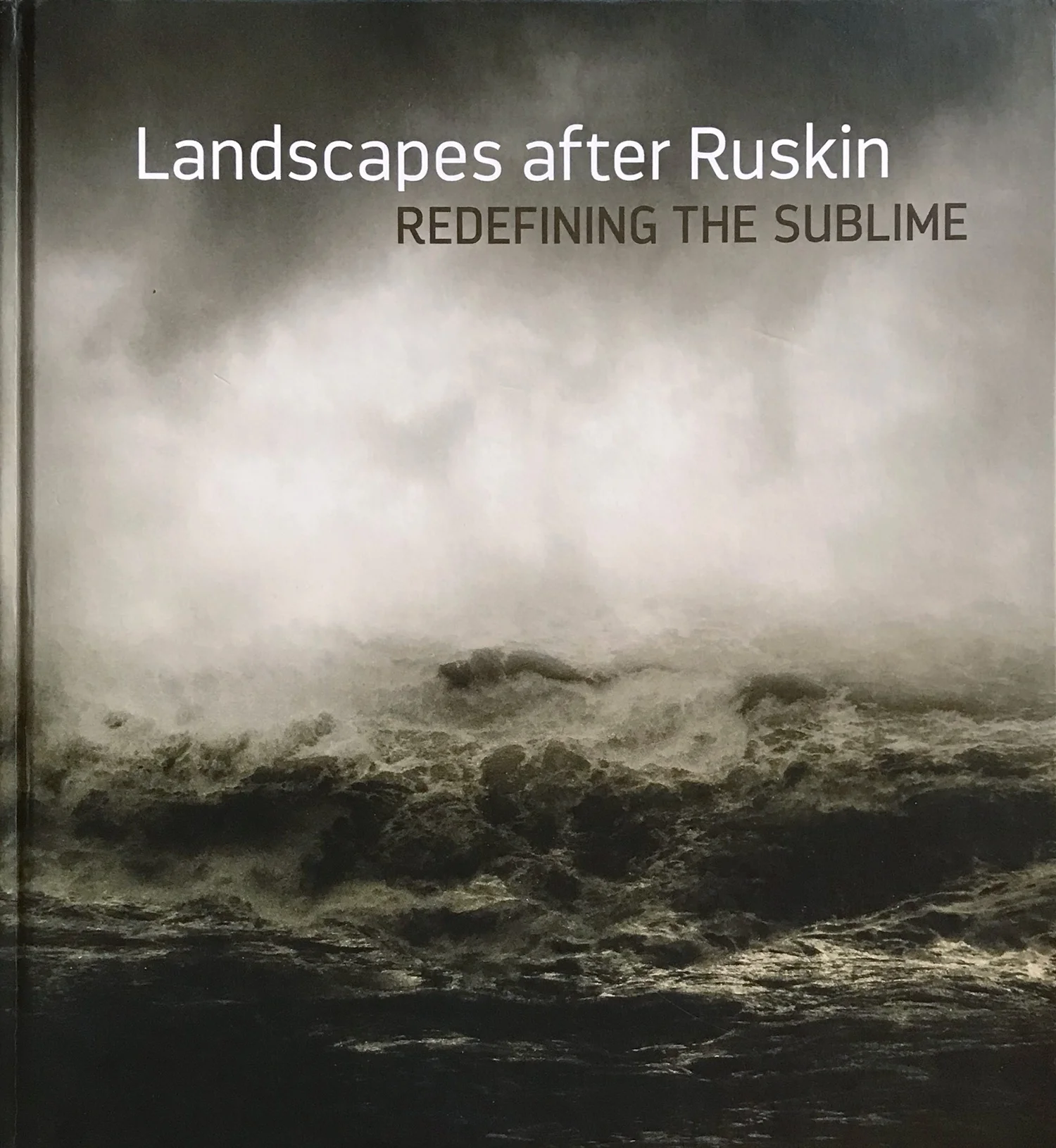

From: Landscapes after Ruskin: Redefining the Sublime - ISBN 978-3-7774-2989-2

In 1840 J. M. W. Turner, the painter seemingly born to make atmospheric landscapes and seascapes of the blowsy weather of the British Isles, was entering what would be the final decade of his life. After forty years of exhibiting his work at the Royal Academy of Arts, his vision began to soar — to take on a whole new freedom and wildness.

A new cloud of controversy about his work and his life arose around him like one of the swirling passages in his paintings.

“He paints now as if his brains and imagination were mixed up on his palette with soapsuds and lather,” wrote the critic William Beckford. Accused of painting with, “cream or chocolate or yolk of egg or current jelly… His whole array of kitchen stuff,” Turner was in need of some aesthetic justification.

Enter John Ruskin, a wealthy young aesthete who had recently studied at Oxford. In time he would become one of the great and controversial voices of the 19th Century, not only as a critic of art but also as a radical social theorist — an advocate for working men and for utopian communities. However, for the moment he was living under the thumb of his ambitious wine merchant father and his controlling mother (who had taken rooms at Oxford to better supervise him). Ruskin was forty years younger than Turner when they met at a garden party.

“Everybody has described him to me as coarse, boorish, unintellectual, vulgar,” wrote Ruskin. “This I know to be impossible.” Rather, Ruskin felt that he had been introduced to a man who was “the greatest in every faculty of the imagination, in every brand of scenic knowledge, at once the painter and the poet of the day.”

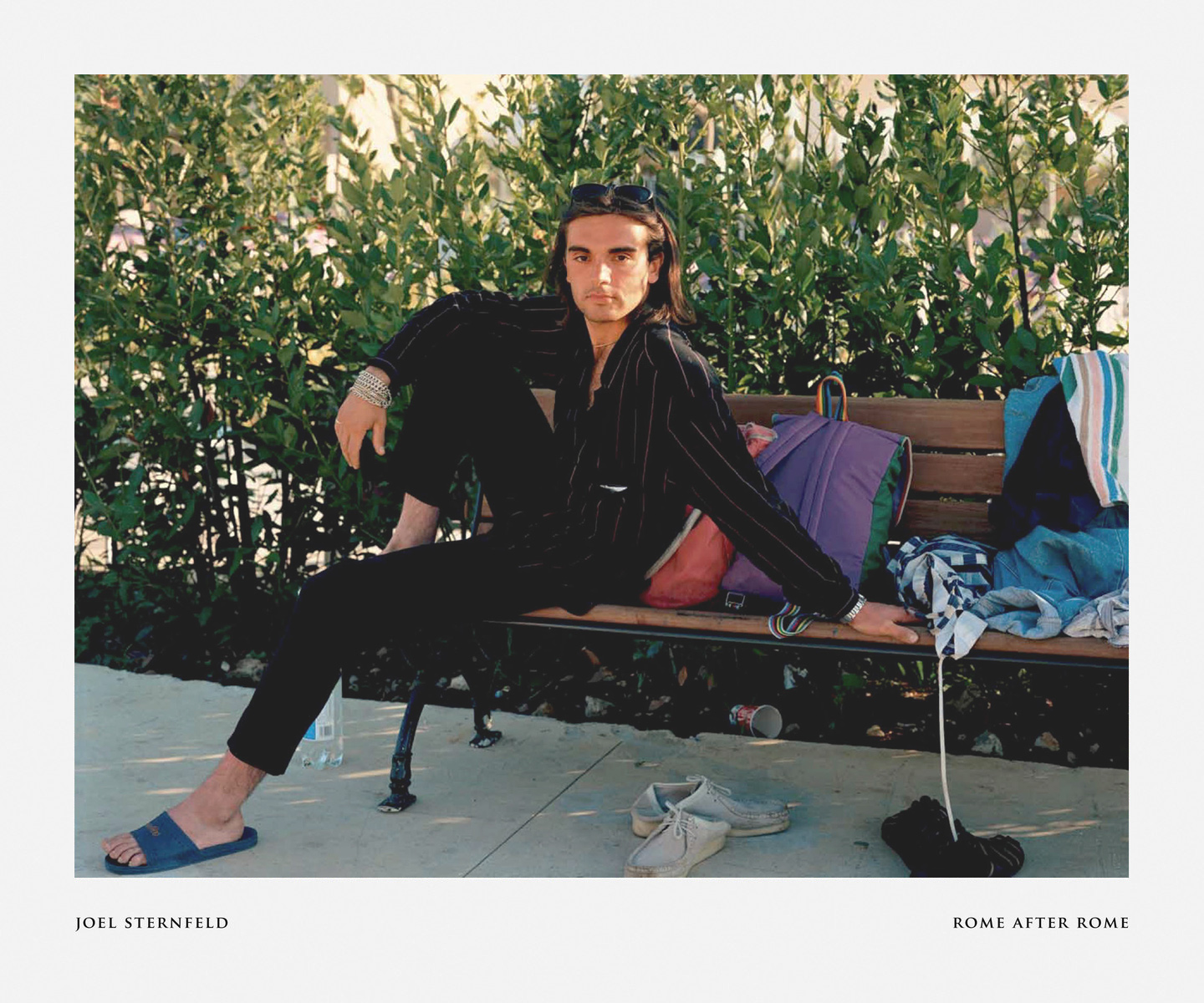

A year after that initial meeting, Ruskin, traveling in Rome, coughing up blood and believing himself to be dying of consumption, vowed to spend what remained of his soon to be short life writing a study of Turner.

Two years later, the first volume of Modern Painters was indeed published. It’s full title was Modern Painters: Their Superiority in the Art of Landscape Painting To all the Ancient Masters proved by Examples of the True, the Beautiful and the Intellectual, from the Works of Modern Artists, Especially From those of J.M.W. Turner, Esq., R.A. By a Graduate of Oxford.

Among the “ancients” that Ruskin found Turner superior to were Claude Lorrain, Gaspard Poussin, Salvator Rosa, Saloman van Ruysdael and Canaletto.

How is it, youthful bravado aside, that Ruskin was able to dismiss the Western landscape tradition in a single phrase?

One cannot discount the possibility that Ruskin was unconsciously drawn to Turner’s freedom and radicalism as a subjugation for his own lack of independence under the reign of his parents and was therefore willing to make extreme claims.

Much more to the point, it just so happened that the landscape tradition, at the moment when Turner and Ruskin made their respective marks on it, was not extensive— especially when measured against the time scale of human cognitive activity that began somewhere between seventy and thirty thousand years ago.

In the various caves with artwork that have been discovered around the globe from the prehistoric period, we see actual handprints and depictions of bison or birds and occasionally humans, but we do not see horizon lines. It would have been so simple to add a horizontal line and situate us in a landscape and yet it was unwanted by those early artists about whose intentions we can only speculate.

Leaping forward in time we see the landscape in Roman wall art in Pompeii, but it is only there as a setting for the actions of humans and deities; there is no appreciation of landscape per se. This is generally the position of landscape throughout the medieval period and the Renaissance in Italy— it is the place where important human matters or myths occur.

It is not until the early 1500s that landscape as we know it begins to get painted. It is difficult to say whether it begins in the canvases of Joachim Patinir in Antwerp, which are not devoid of human or religious drama but which place unprecedented emphasis on the sky and earth, or if it begins in the small Dutch or Flemish paintings that are simultaneously being made, but somehow there is a shift in sensibility, a new appreciation of physical surround. All this finds its full flowering in the Golden Age of Painting in Holland and the Flemish Baroque, which Ruskin astonishingly dismisses as the various “Van somethings” and “Beck - somethings”.

In the late 1600s artists shift their attention to Rome, and in particular to the ruin-dotted countryside south and east of the city. Religious and historical subject matter dominates in their work with the landscape treated as an idealized Arcadian set. Ironically enough, the sometimes-malarial plane of the Roman Campagna that Herman Melville, decades later, would refer to as “Rome’s accursed compagna” becomes the locus for a glowing and golden mythological past that exists in the collective Western imagination, if nowhere else.

Thus, when Turner shows up with his paintings that give a leading role to the ever-stirring stew of British weather, it is not without reason that Ruskin can claim their virtue as “truth to nature.” If they are not altogether completely true to it, they at least pay more attention to it than anyone had previously. The sky, the light, the very atmosphere that permits us to live on earth itself are at the heart of Turner’s enterprise.

In exclaiming Turner’s work, Ruskin leans on the British philosopher Edmund Burke and the German philosopher Immanuel Kant for gravitas in the theory of the sublime (very roughly: a kind of cathartic moment, received from viewing the scale and power of nature—albeit from a safe distance). In extolling the sublimity in Turner’s paintings, Turner may be part of a movement that was–bad pun–in the air. Sublimity was a popular concept; people were looking for pleasurable or fulfilling terror in general.

Why, one might ask, did it take so long for landscape itself to become a subject for painting? It is possible it has to do with a phenomenon described by David Foster Wallace in a commencement speech at Kenyon College.

“There are these two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, ‘Morning, boys, how's the water?’ And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, ‘What the hell is water?’”

For our purposes, “What the hell is landscape?” Another reason painters may not have privileged landscape is that throughout human history the landscape, rather than being a gentleman farmer Cicero’s delight, was a constant source of not at all real fear and a delightful danger. Large predators, storms and other natural phenomena, invading armies, robbers and brigands, you name it, the landscape constantly contained the possibility of death. The castles we now find so romantic were cold and damp fortresses and armored camps that might or might not protect.

England was particularly dangerous. The great contemporary scholar of landscape Yi-Fu Tuan notes that medieval England was widely known throughout Europe for its high rate of crime. He quotes one Italian visitor to that presumably green and pleasant land around 1500 who declares, “in no country in the world are there more robbers and thieves than in England; insomuch that few venture to go alone in the country, except in the middle of the day, and fewer still in the towns at night.”

Only when an artist can wander freely and safely in the landscape can a plein air tradition begin. It is possible to speculate that landscape painting began in China in the eighth century, some seven hundred years before it did in the West, not only because of keen appreciations of gardens and nature but also because the T’ang Empire was so well governed that the countryside was utterly safe.

Turning back to England, by the 1760s the Industrial Revolution was arriving and with it the first trains (1804). Of course it cannot simply be a coincidence that John Constable, born in 1776, one year after Turner, started painting his pastoral scenes and exhibiting them at the Royal Academy (1799). His work received a mixed reception, in part because it was generally known just how backbreaking and boring farm life could be and therefore it was not considered an ennobling subject matter.

Casper David Friedrich, born in 1774, one year before Turner, begins exhibiting his almost Wagnerian scenes of lonely souls in the mountains or in gothic landscapes. His work resonates not only because of its power, but also because it coincides with a time when mountain or alpine tourism was growing in popularity in Europe and America. The Romantic painters and the proto-adventure tourists may be responding to the same impulse.

For a few years in the world, the sublime flourishes as an aesthetic. To an industrialist or to a harried city dweller, the idea of nature, cupped with a frisson of fear, may titillate dulled sensibilities. That doesn’t last: in fairly short order modernity truly descends, the world is industrialized, corporatized, and frightening. By 1867 Matthew Arnold while on his honeymoon and listening to waves at night can write that the world:

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor life,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain.

His poem, “Dover Beach,” perhaps the first poem of the modern era, seems to know that mass warfare, atomic weaponry, all-pervasive pollution, and a planet struggling to drink and to breathe is coming.

In fact, late in his life, Ruskin, after fifty years of intense observations of sunsets and of the sky, gives a series of lectures, which are published as The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century (1884). Presciently, he describes the effects of industrialization on weather patterns and the atmosphere.

Of course artists vibrate to change in the political and social environment– landscape is, and a broad sense, a visualization of consciousness. As soon as the period dominated by the so-called Impressionist and by Cézanne, who may have been influenced by Turner, is over, artists turn an eye to the landscape as it truly is. “Truth to nature” becomes “truth to place.” Courbet may paint an angry wave, but a hundred and some years later, Ai Weiwei sculpts an oil slick.

In fact, painting may lend itself to the “truth of nature” now more than photographs. Much of pollution and its consequences are invisible to the camera, but a painter may use strategies to reference them.

In the course of a century like no other, a truly terrifying sublime has arisen. For a few short years when Turner and Constable and Friedrich were working, and Ruskin was justifying Turner’s efforts in what Walter Benjamin has termed “the summary mid 19th-century,” it was possible to experience what we can now with hindsight regard as an innocent sublime. With the return of landscape to its ongoing default condition as a place of mortal fear and danger to humans, we have only a calamitous sublime to behold.