To Joseph Palmer - text by Stewart Holbrook

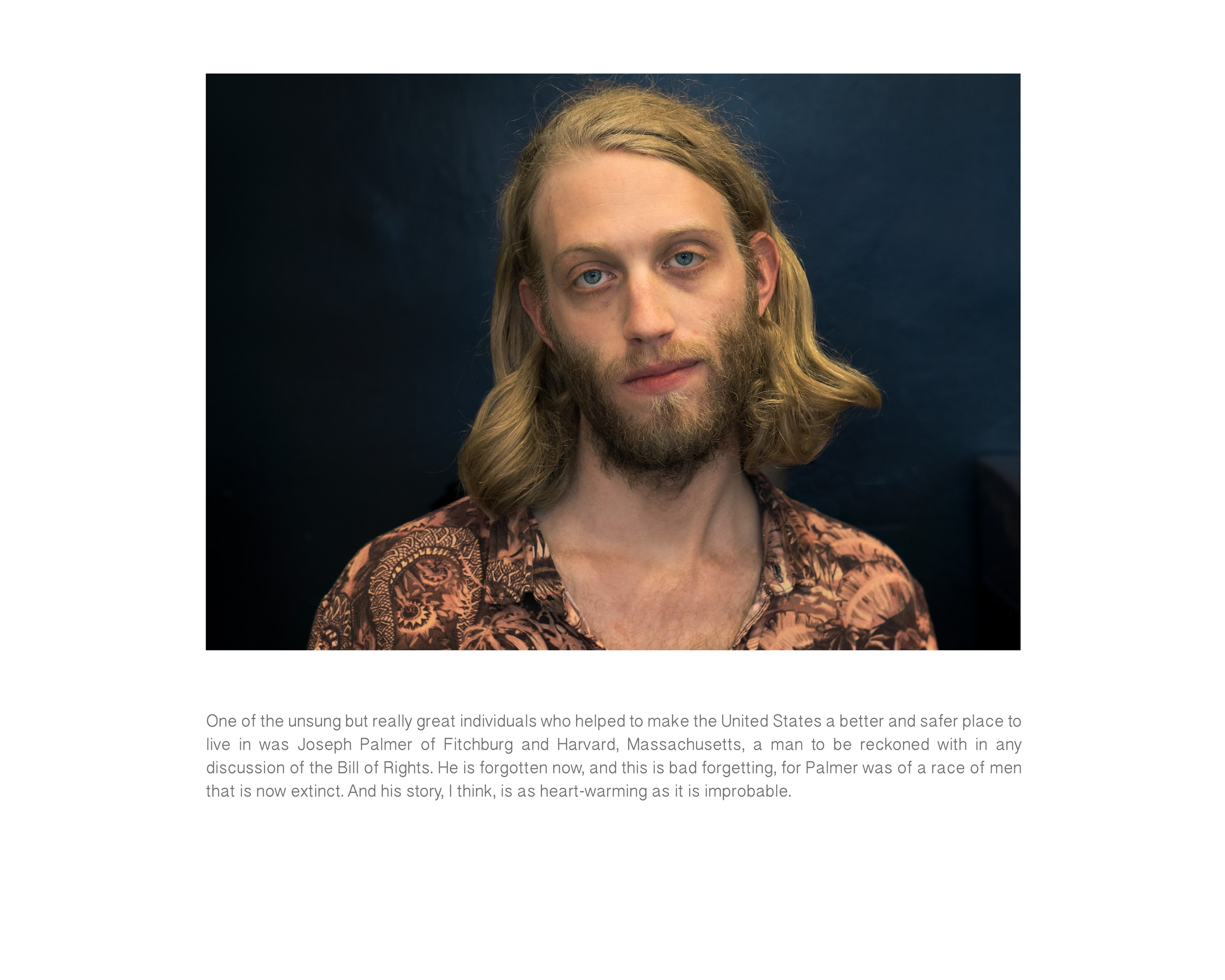

One of the unsung but really great individuals who helped to make the United States a better and safer place to live in was Joseph Palmer of Fitchburg and Harvard, Massachusetts, a man to be reckoned with in any discussion of the Bill of Rights. He is forgotten now, and this is bad forgetting, for Palmer was of a race of men that is now extinct. And his story, I think, is as heart-warming as it is improbable.

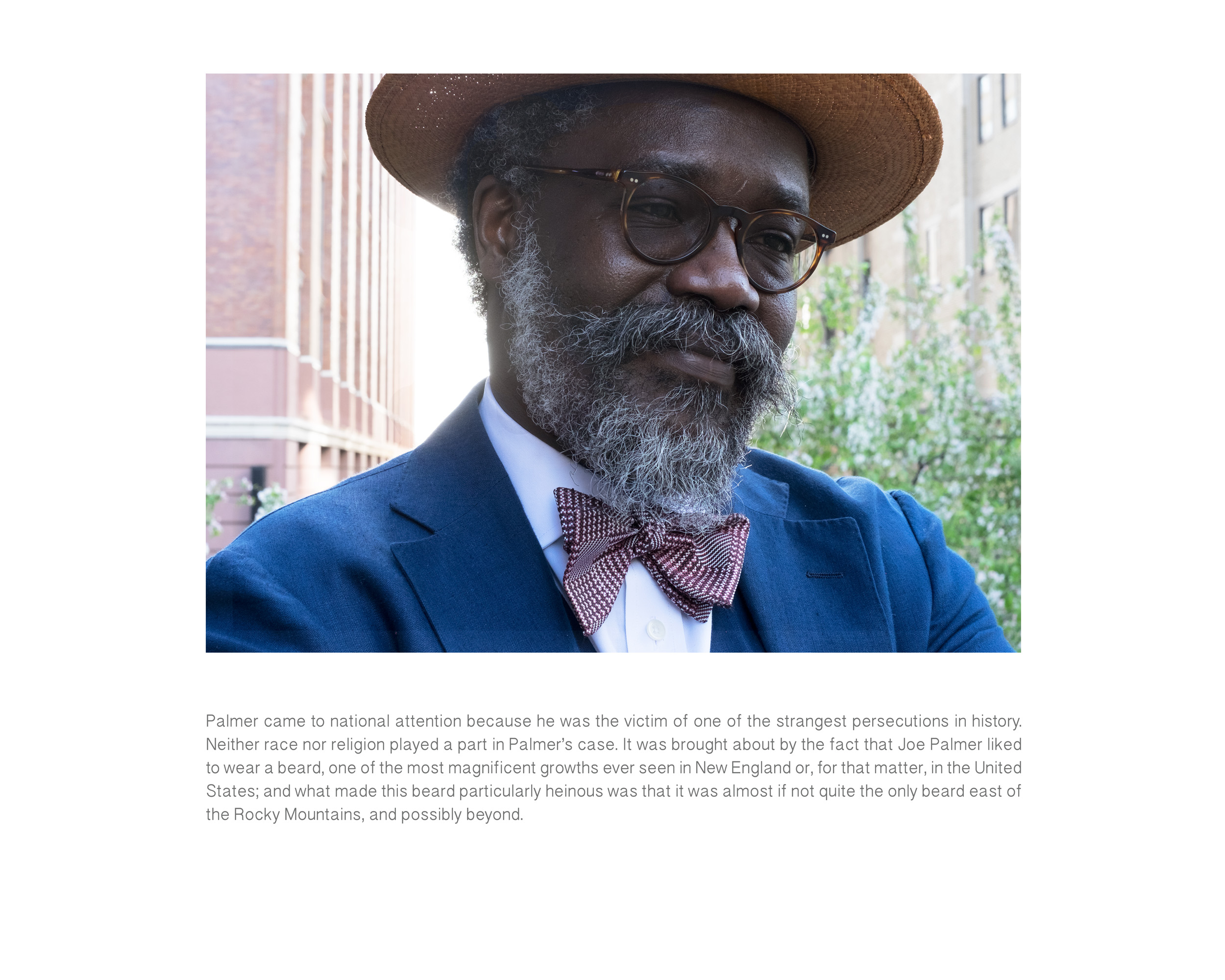

Palmer came to national attention because he was the victim of one of the strangest persecutions in history. Neither race nor religion played a part in Palmer’s case. It was brought about by the fact that Joe Palmer liked to wear a beard, one of the most magnificent growths ever seen in New England or, for that matter, in the United States; and what made this beard particularly heinous was that it was almost if not quite the only beard east of the Rocky Mountains, and possibly beyond.

One lone set of whiskers amid millions of smooth-shaved faces is something to contemplate, and Palmer paid dearly for his eccentricity. Indeed, one might say that it was Joe Palmer who carried the Knowledge of Whiskers through the dark ages of beardless America. He was born almost a century too late and seventy-five years too soon to wear whiskers with impunity. He was forty-two years old in 1830, when he moved from his nearby farm into the hustling village of Fitchburg. He came of sturdy old Yankee stock. His father had served in the Revolution, and Joe himself had carried a musket in 1812. He was married and had one son, Thomas.

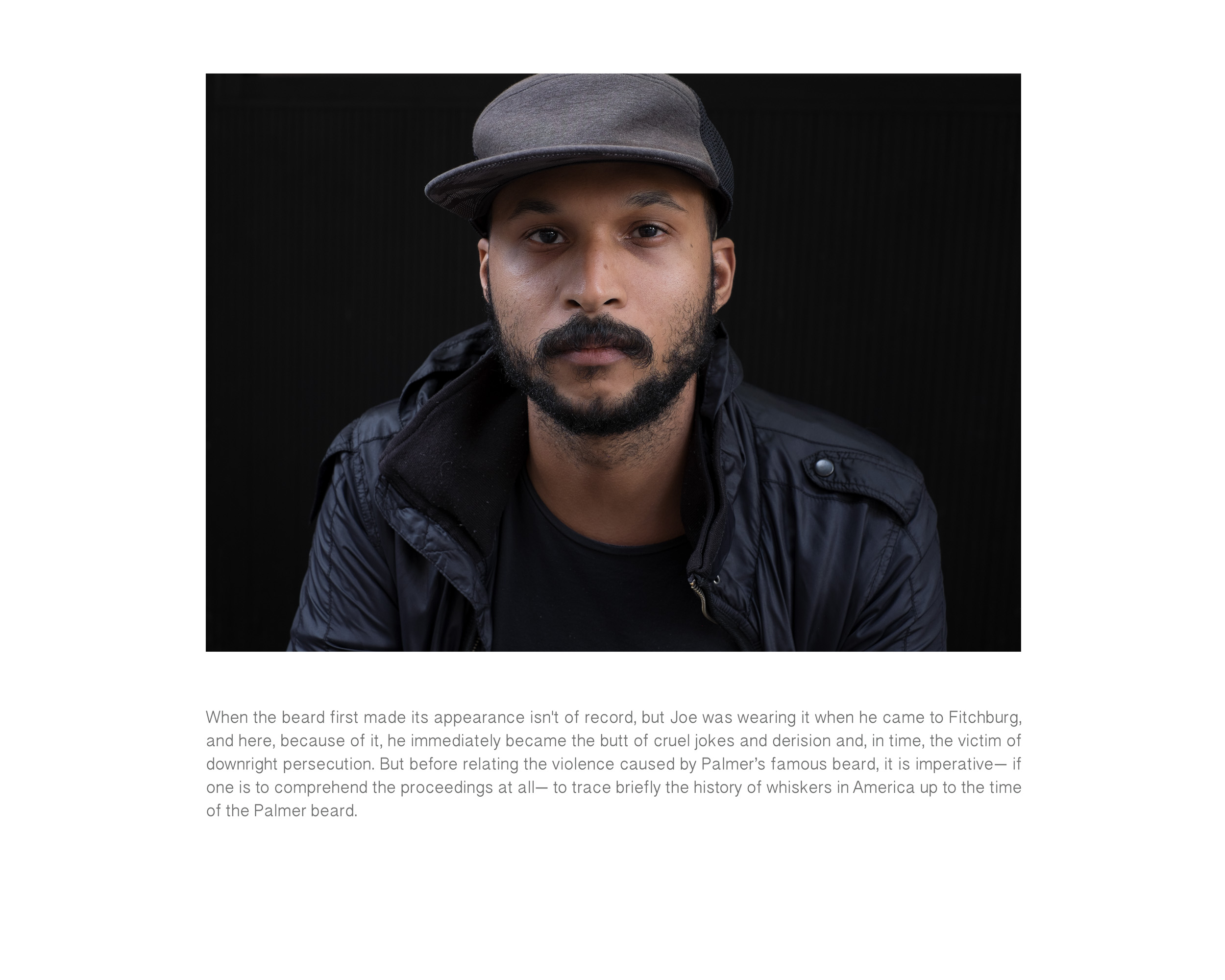

When the beard first made its appearance isn't of record, but Joe was wearing it when he came to Fitchburg, and here, because of it, he immediately became the butt of cruel jokes and derision and, in time, the victim of downright persecution. But before relating the violence caused by Palmer’s famous beard, it is imperative— if one is to comprehend the proceedings at all— to trace briefly the history of whiskers in America up to the time of the Palmer beard.

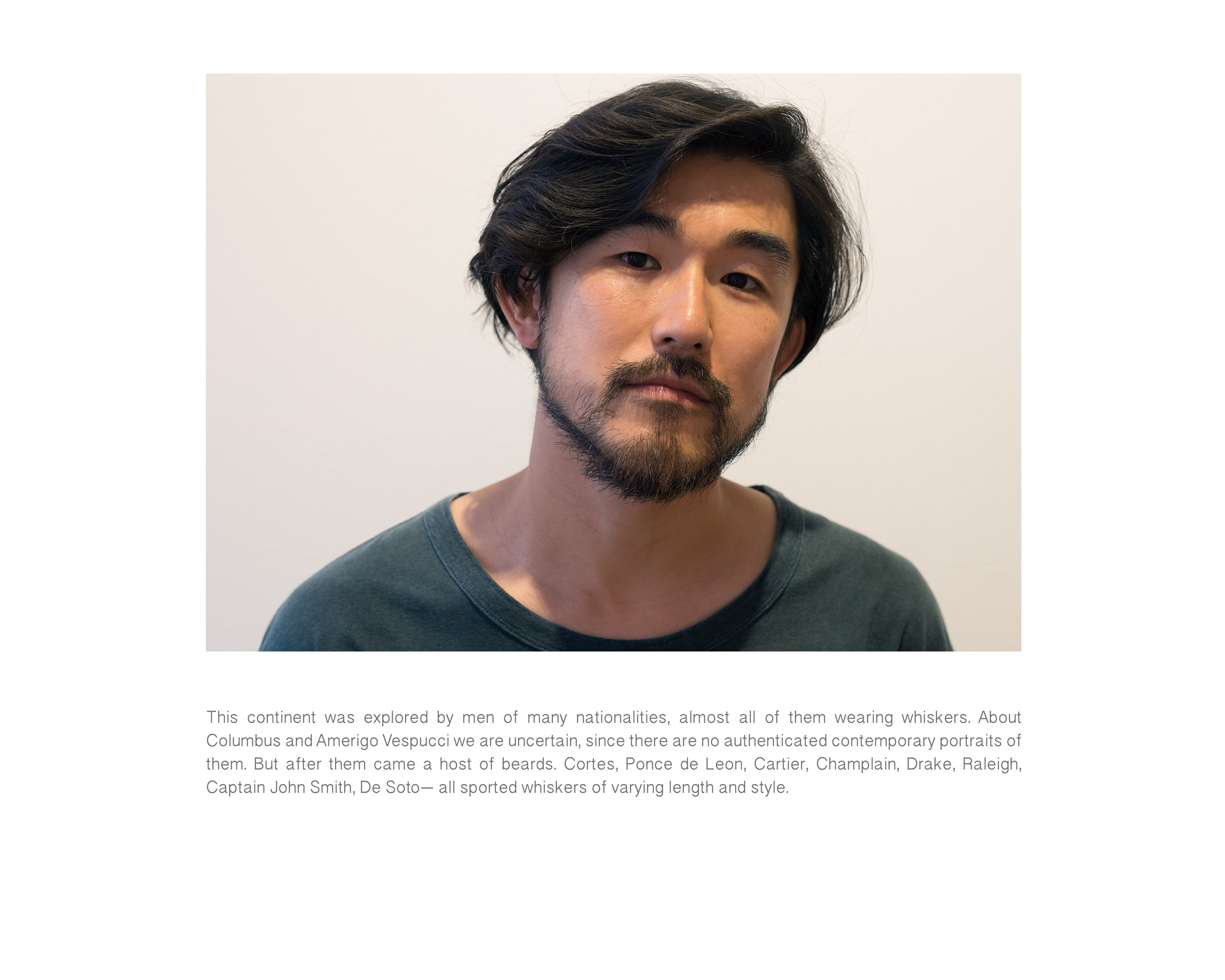

This continent was explored by men of many nationalities, almost all of them wearing whiskers. About Columbus and Amerigo Vespucci we are uncertain, since there are no authenticated contemporary portraits of them. But after them came a host of beards. Cortes, Ponce de Leon, Cartier, Champlain, Drake, Raleigh, Captain John Smith, De Soto— all sported whiskers of varying length and style.

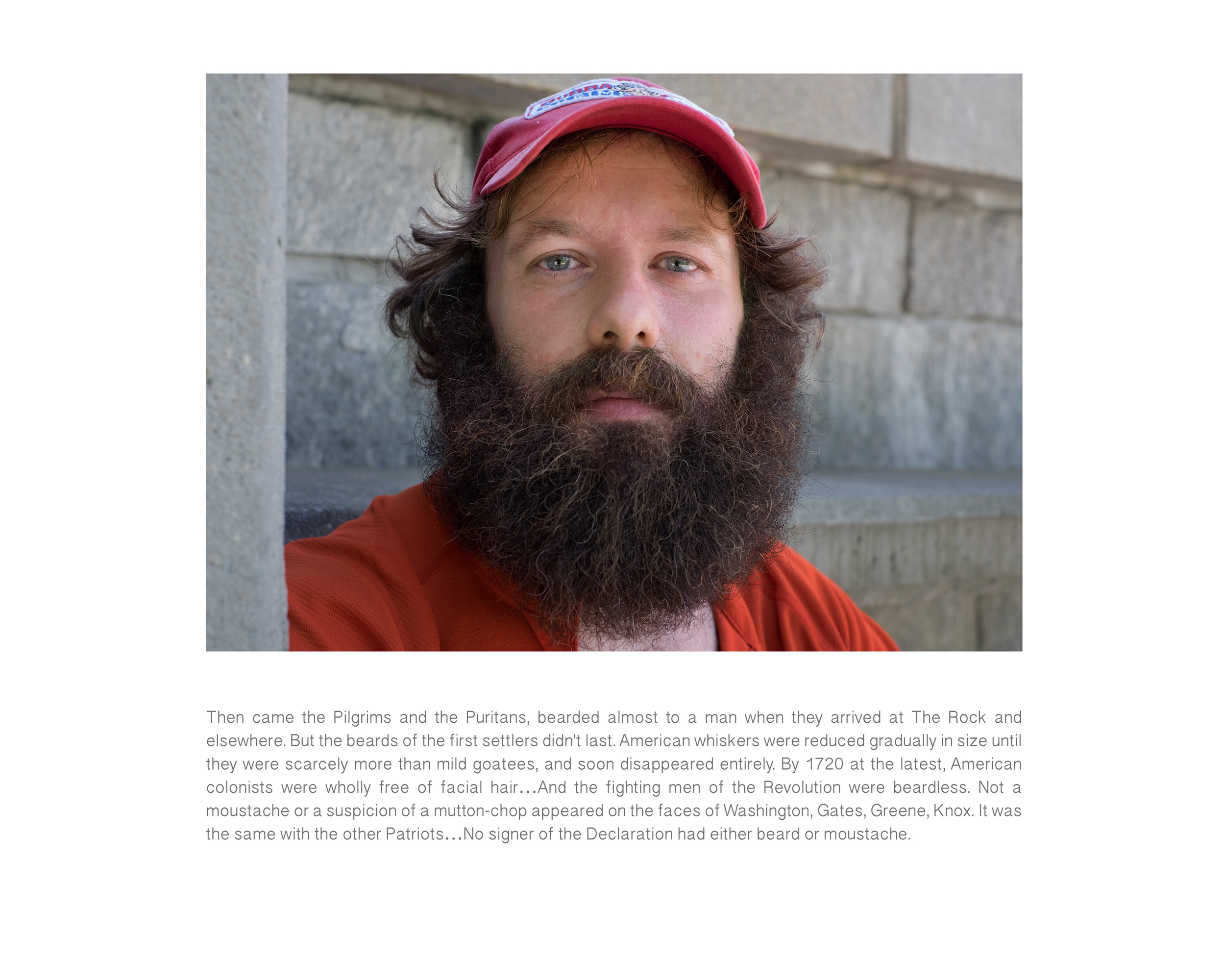

Then came the Pilgrims and the Puritans, bearded almost to a man when they arrived at The Rock and elsewhere. But the beards of the first settlers didn't last. American whiskers were reduced gradually in size until they were scarcely more than mild goatees, and soon disappeared entirely. By 1720 at the latest, American colonists were wholly free of facial hair…And the fighting men of the Revolution were beardless. Not a moustache or a suspicion of a mutton-chop appeared on the faces of Washington, Gates, Greene, Knox. It was the same with the other Patriots…No signer of the Declaration had either beard or moustache.

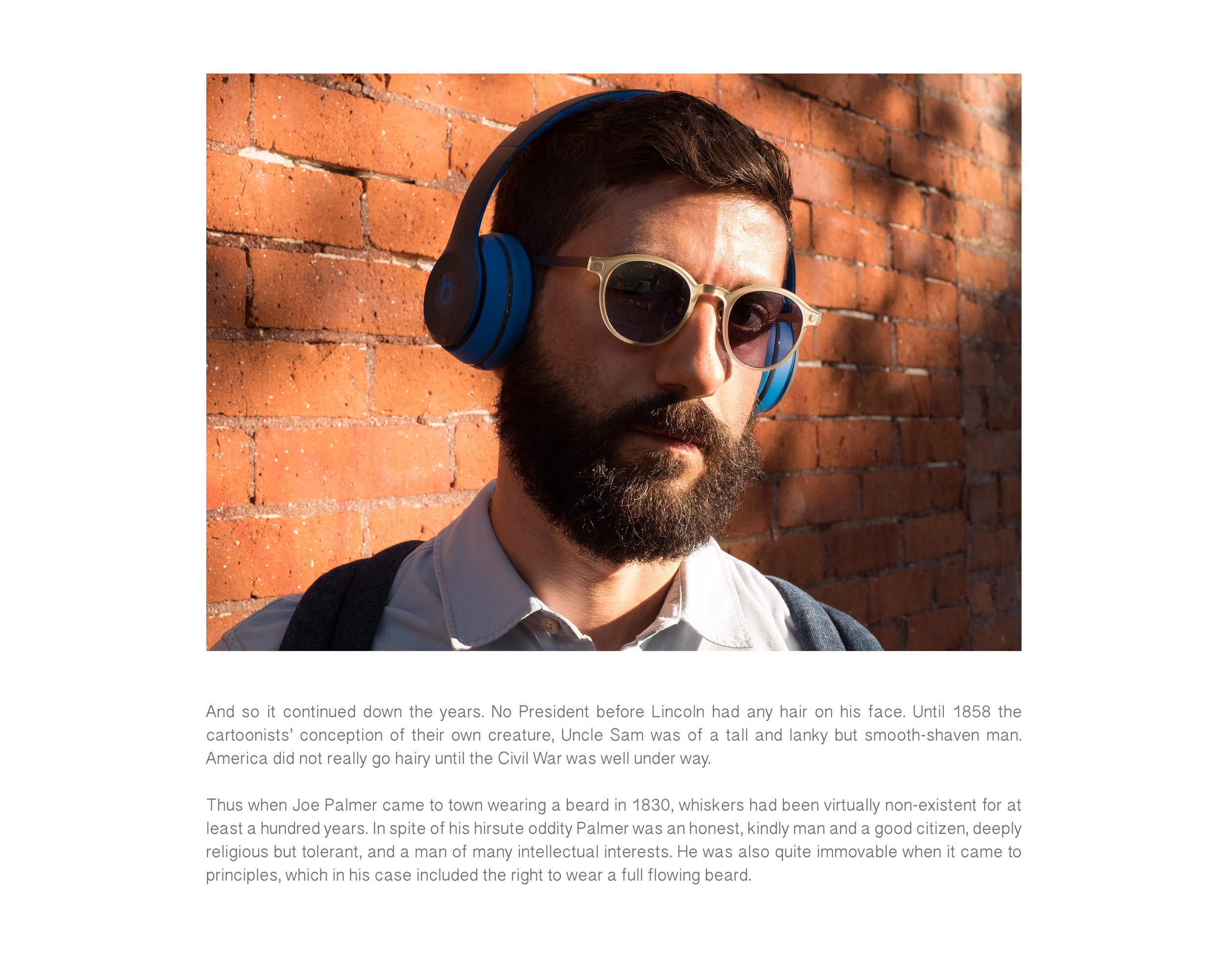

And so it continued down the years. No President before Lincoln had any hair on his face. Until 1858 the cartoonists’ conception of their own creature, Uncle Sam was of a tall and lanky but smooth-shaven man. America did not really go hairy until the Civil War was well under way. Thus when Joe Palmer came to town wearing a beard in 1830, whiskers had been virtually non-existent for at least a hundred years. In spite of his hirsute oddity Palmer was an honest, kindly man and a good citizen, deeply religious but tolerant, and a man of many intellectual interests. He was also quite immovable when it came to principles, which in his case included the right to wear a full flowing beard.

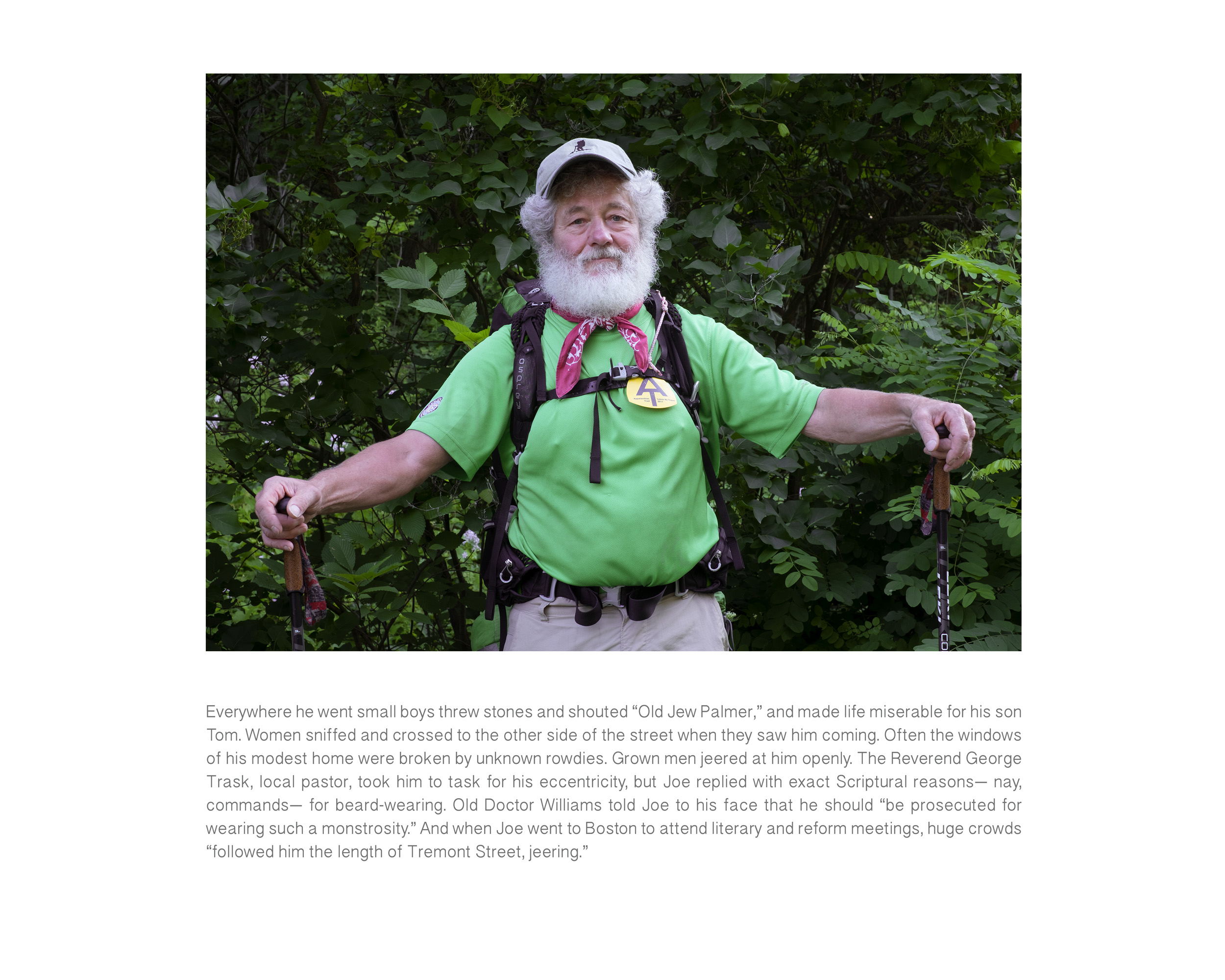

Everywhere he went small boys threw stones and shouted “Old Jew Palmer,” and made life miserable for his son Tom. Women sniffed and crossed to the other side of the street when they saw him coming. Often the windows of his modest home were broken by unknown rowdies. Grown men jeered at him openly. The Reverend George Trask, local pastor, took him to task for his eccentricity, but Joe replied with exact Scriptural reasons— nay, commands— for beard-wearing. Old Doctor Williams told Joe to his face that he should “be prosecuted for wearing such a monstrosity.” And when Joe went to Boston to attend literary and reform meetings, huge crowds “followed him the length of Tremont Street, jeering.”

Joe Palmer was a national character, made so by two events that had happened in quick succession in his hometown of Fitchburg. In spite of the snubs of the congregation, Joe never missed a church service, but one Sunday he quite justifiably lost his usually serene temper. It was a Communion Sunday in 1830. Joe knelt with the rest, only to be publicly humiliated when the officiating clergyman ignored him, “passed him by with the communion bread and wine.” Joe was cut to the quick. He rose up and strode to the communion table. He lifted the cup to his lips and took a mighty swig. Then: “I love my Jesus,” he shouted in a voice loud with hurt and anger, “as well, and better, than any of you!” Then he went home.

A few days later, as he was coming out of the Fitchburg Hotel, he was seized by four men armed with shears, brush, soap, and razor. They told him that the sentiment of the town was that his beard should come off and they were going to do the job there and then. When Joe started to struggle, the four men threw him violently to the ground, seriously injuring his back and head. But Joe had just begun to fight. When they were about to apply the shears, he managed to get an old jack-knife out of his pocket. He laid about him wildly, cutting two of his assailants in their legs, not seriously but sufficiently to discourage any barber work. When Joe stood up, hurt and bleeding, his gorgeous beard was intact.

Presently he was arrested, charged with “an unprovoked assault.” Fined by Justice Brigham, he refused to pay. Matter of the principle, he said. He was put in the city jail at Worcester and there he remained for more than a year, part of the time in solitary confinement. Even there he had to fight for his whiskers, for once Jailor Bellows came with several men with the idea of removing the now famous beard. Joe threw himself at them and fought so furiously that the mob retreated without a hair. He also successfully repulsed at least two attempts by prisoners to shave him.

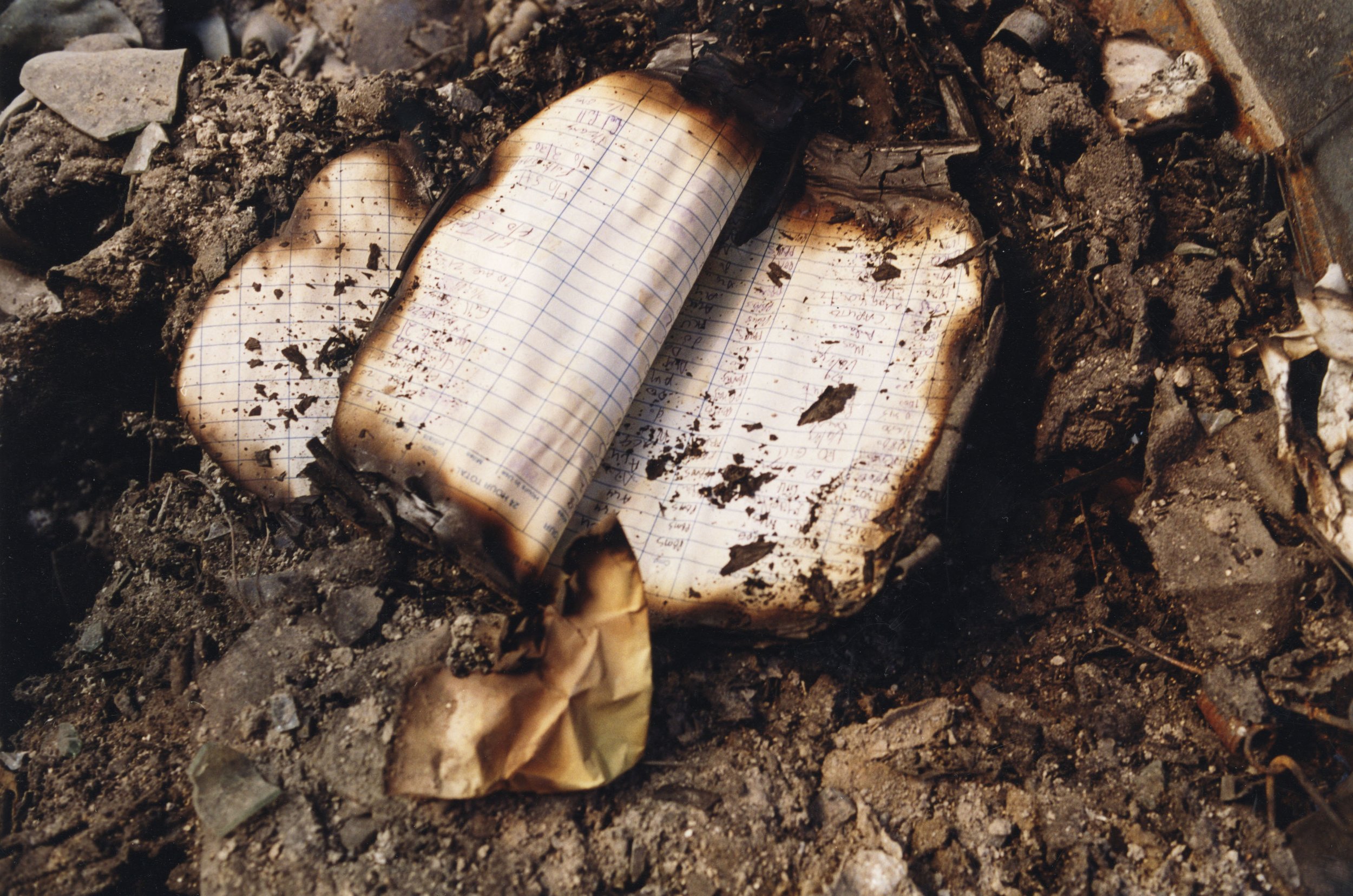

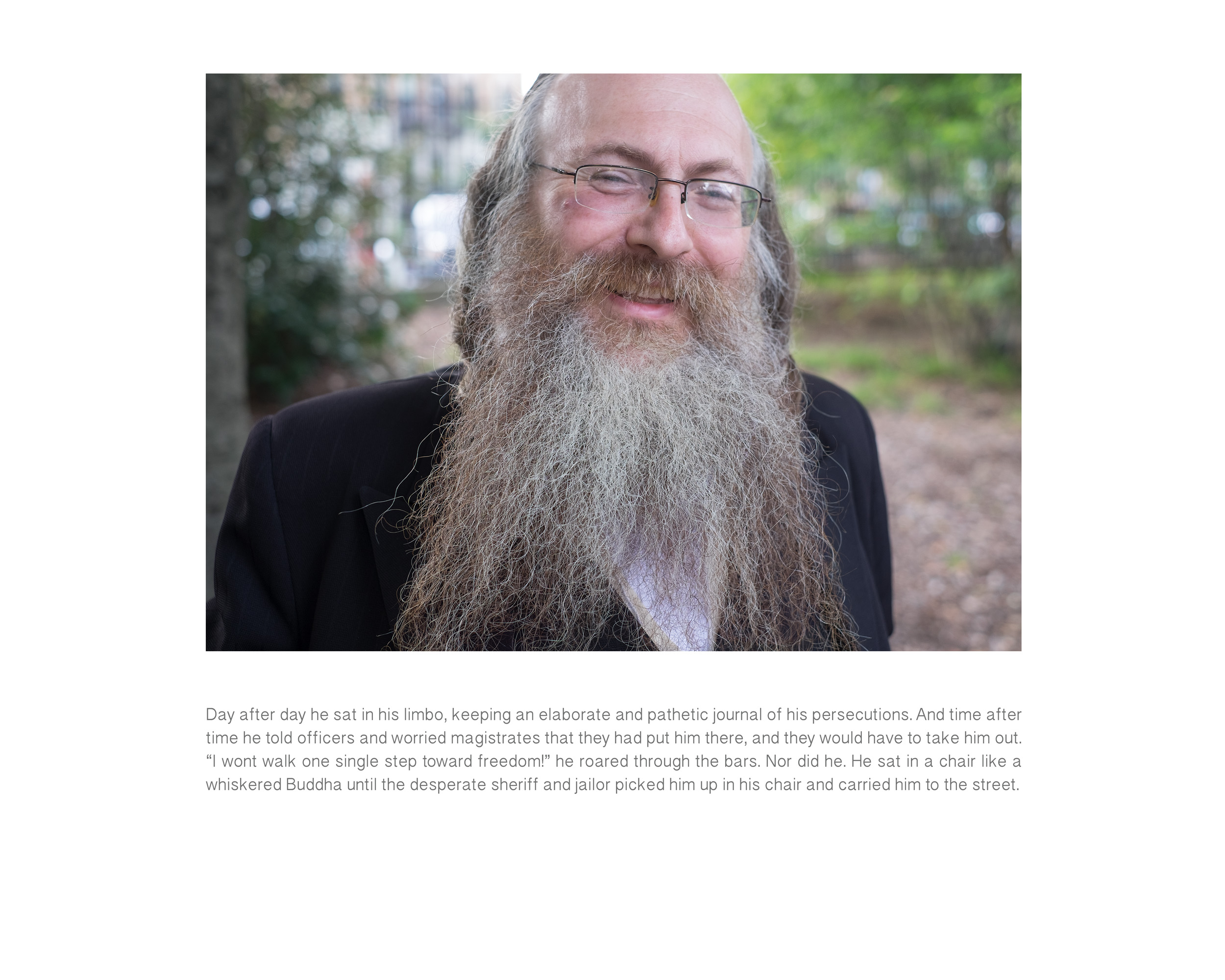

Day after day he sat in his limbo, keeping an elaborate and pathetic journal of his persecutions. And time after time he told officers and worried magistrates that they had put him there, and they would have to take him out. “I wont walk one single step toward freedom!” he roared through the bars. Nor did he. He sat in a chair like a whiskered Buddha until the desperate sheriff and jailor picked him up in his chair and carried him to the street.

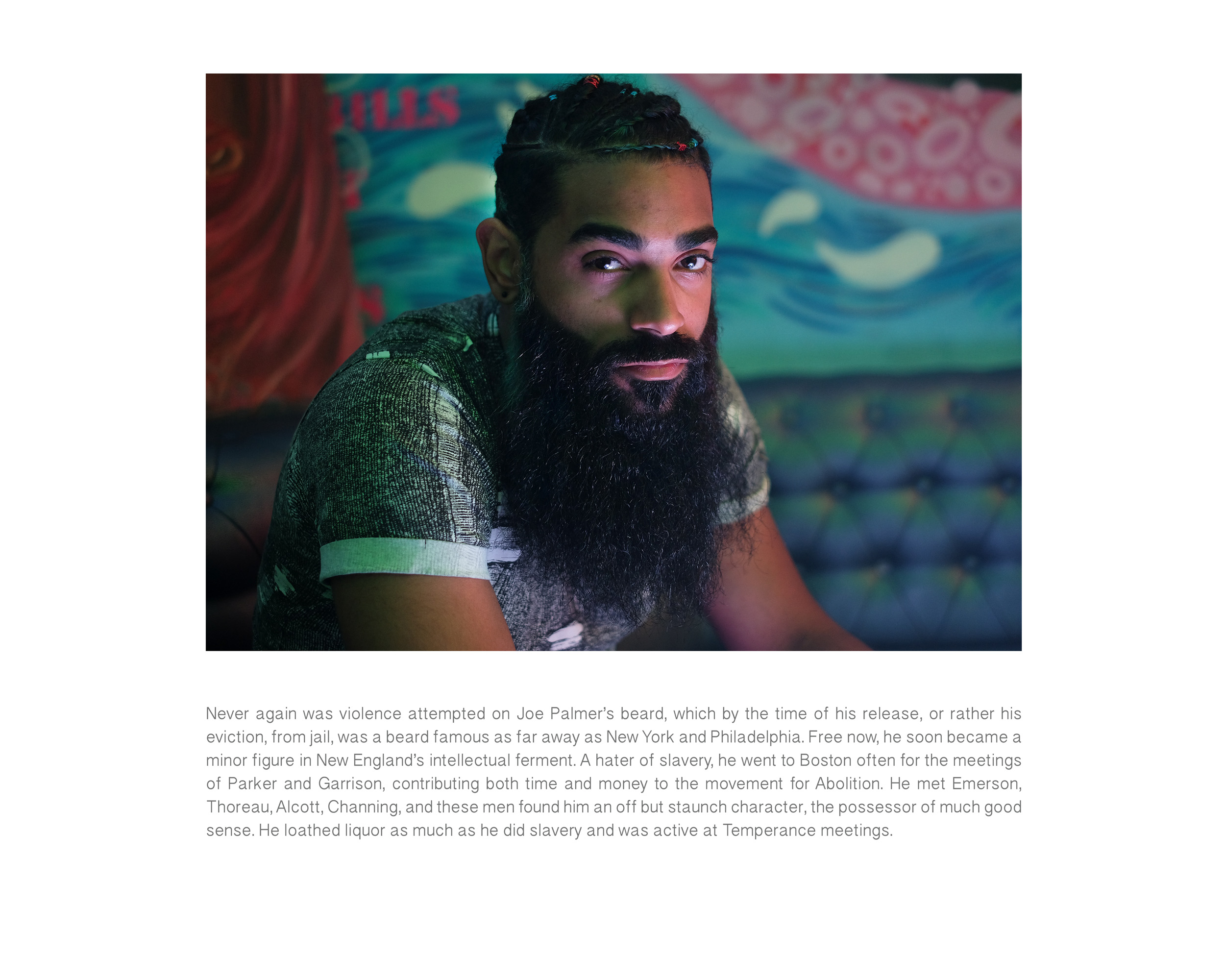

Never again was violence attempted on Joe Palmer’s beard, which by the time of his release, or rather his eviction, from jail, was a beard famous as far away as New York and Philadelphia. Free now, he soon became a minor figure in New England’s intellectual ferment. A hater of slavery, he went to Boston often for the meetings of Parker and Garrison, contributing both time and money to the movement for Abolition. He met Emerson, Thoreau, Alcott, Channing, and these men found him an off but staunch character, the possessor of much good sense. He loathed liquor as much as he did slavery and was active at Temperance meetings.

When Bronson Alcott and family bought a farm in Harvard, near Fitchburg, named it Fruitlands and attempted to found the Con-Sociate Family, Joe Palmer was vastly interested. He donated a lot of fine old furniture and up-to-date farm implements to the colony. When he saw that Alcott’s idiotic ideas about farming were going to bring famine to the group, he brought his own team and plow and turned up the soil. He was, in fact, the only sensible male in that wondrous experiment. (Joe Palmer appears in Louisa May Alcott’s Transcendental Wild Oates as Moses White.)

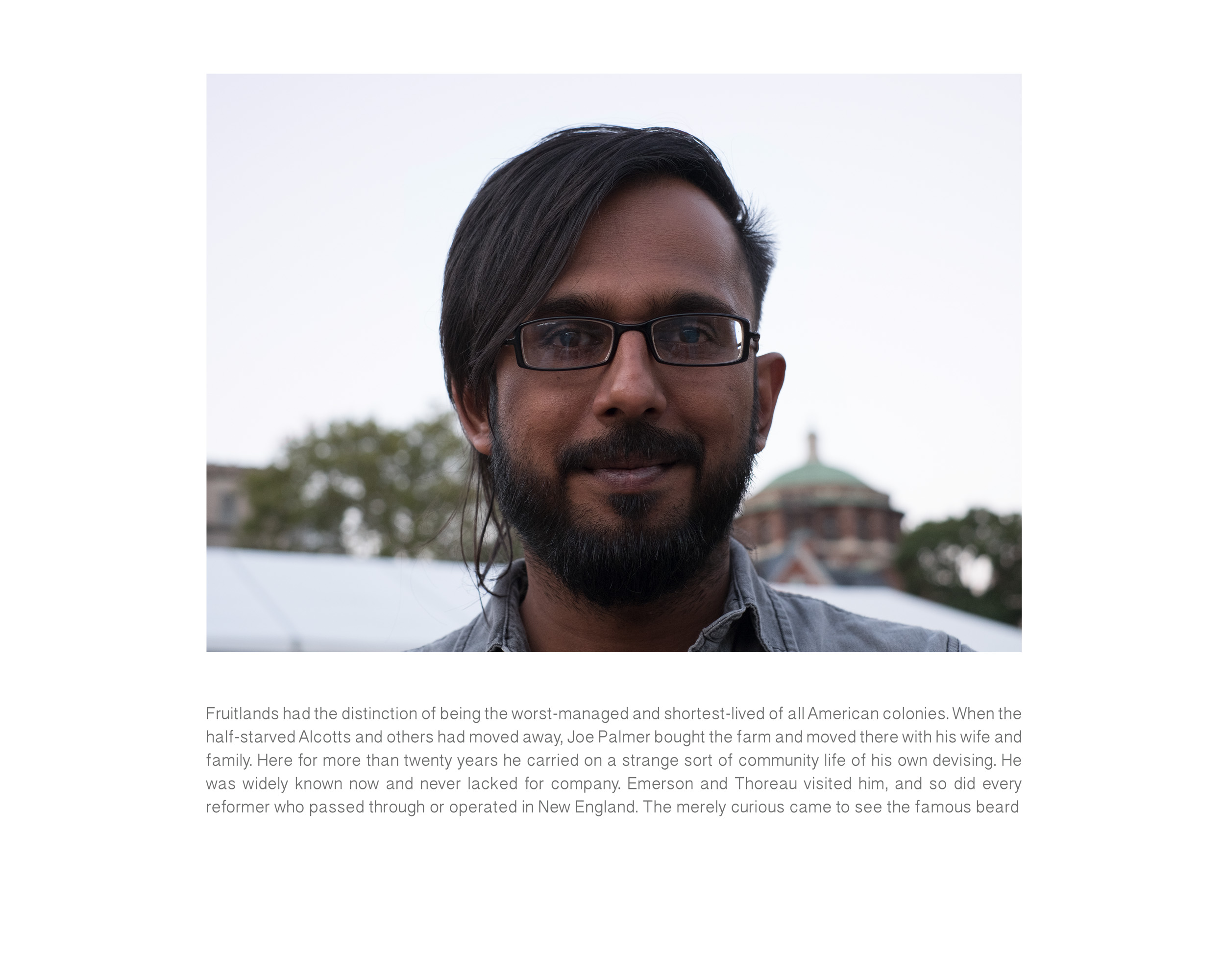

Fruitlands had the distinction of being the worst-managed and shortest-lived of all American colonies. When the half-starved Alcotts and others had moved away, Joe Palmer bought the farm and moved there with his wife and family. Here for more than twenty years he carried on a strange sort of community life of his own devising. He was widely known now and never lacked for company. Emerson and Thoreau visited him, and so did every reformer who passed through or operated in New England. The merely curious came to see the famous beard

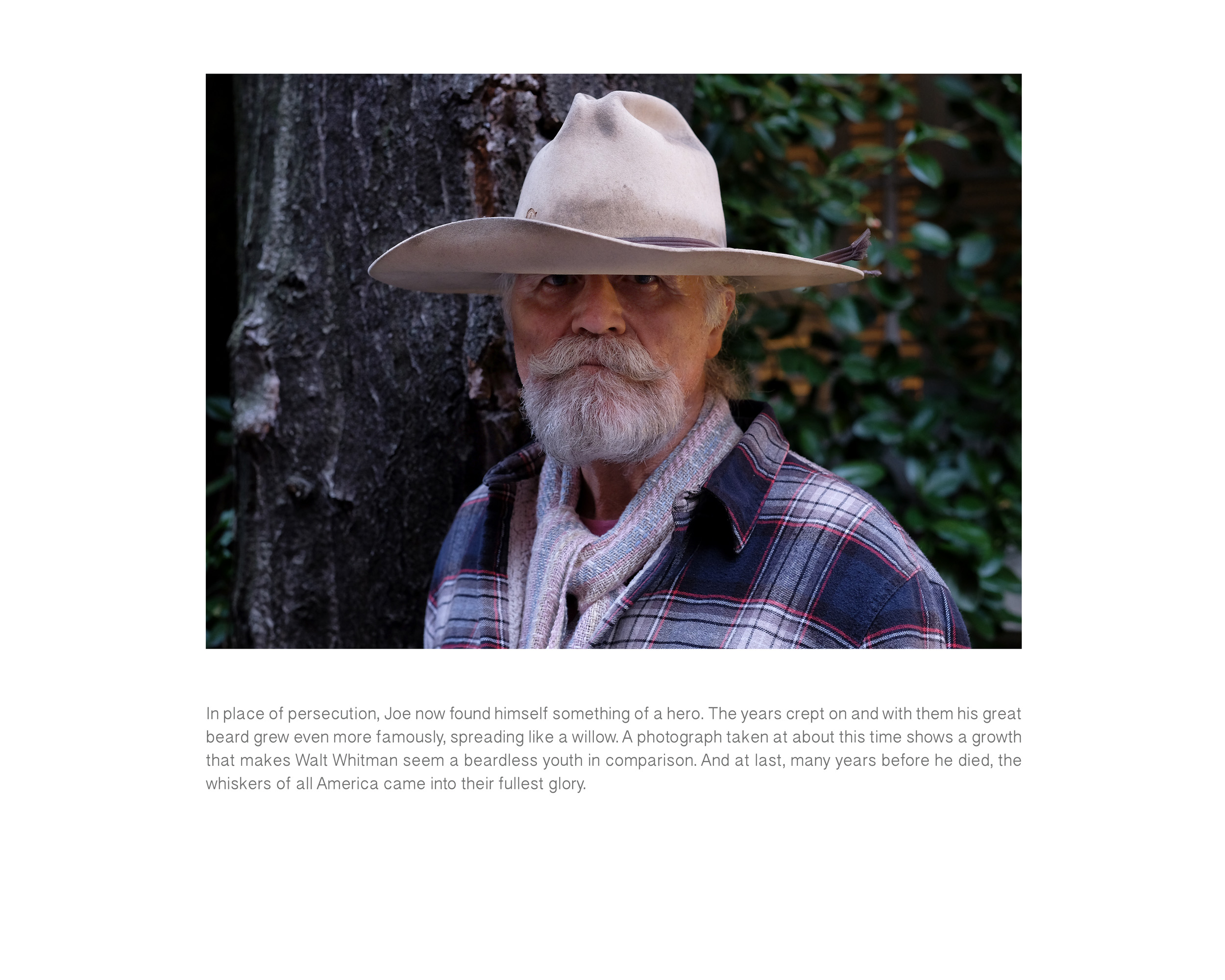

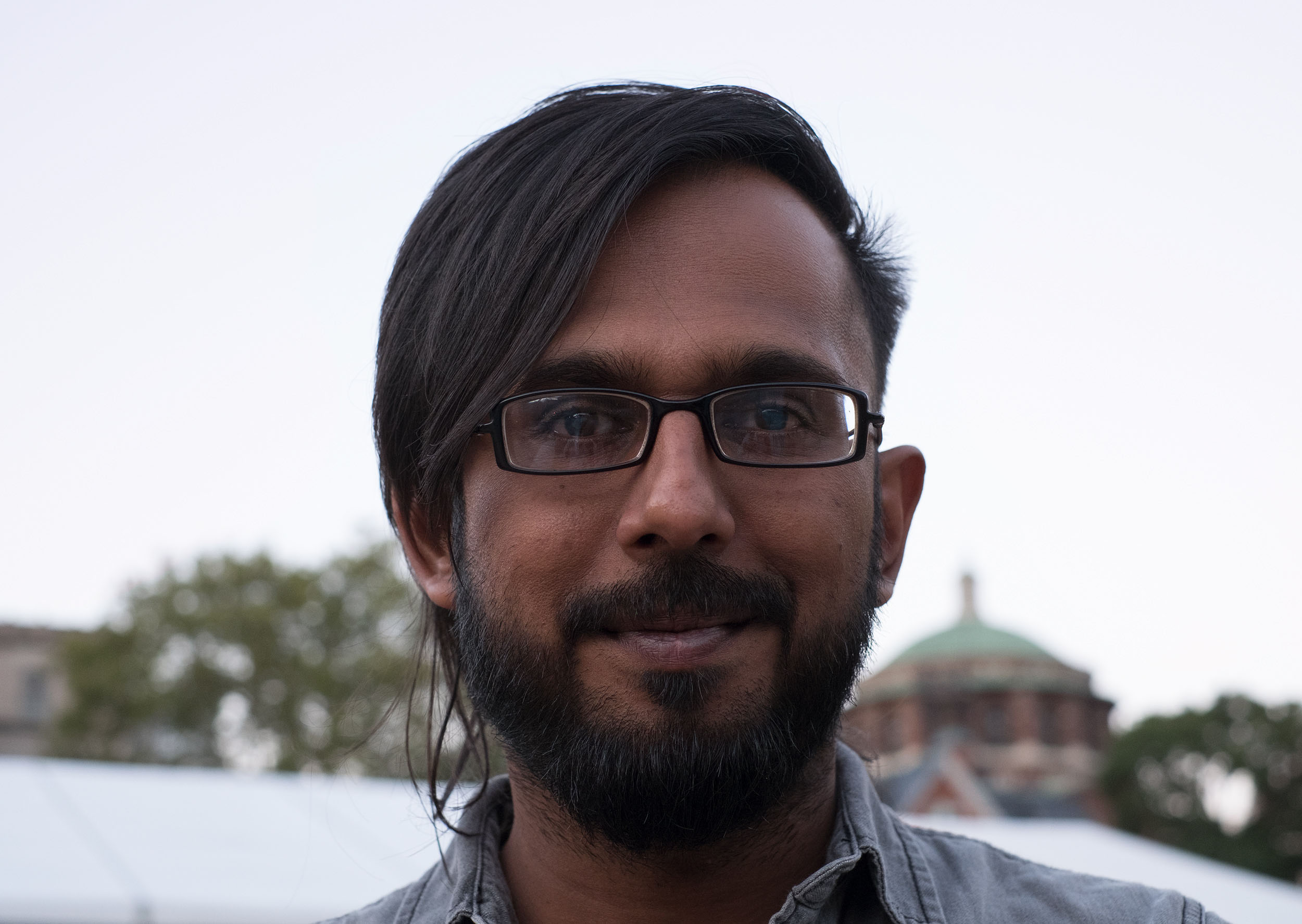

In place of persecution, Joe now found himself something of a hero. The years crept on and with them his great beard grew even more famously, spreading like a willow. A photograph taken at about this time shows a growth that makes Walt Whitman seem a beardless youth in comparison. And at last, many years before he died, the whiskers of all America came into their fullest glory.

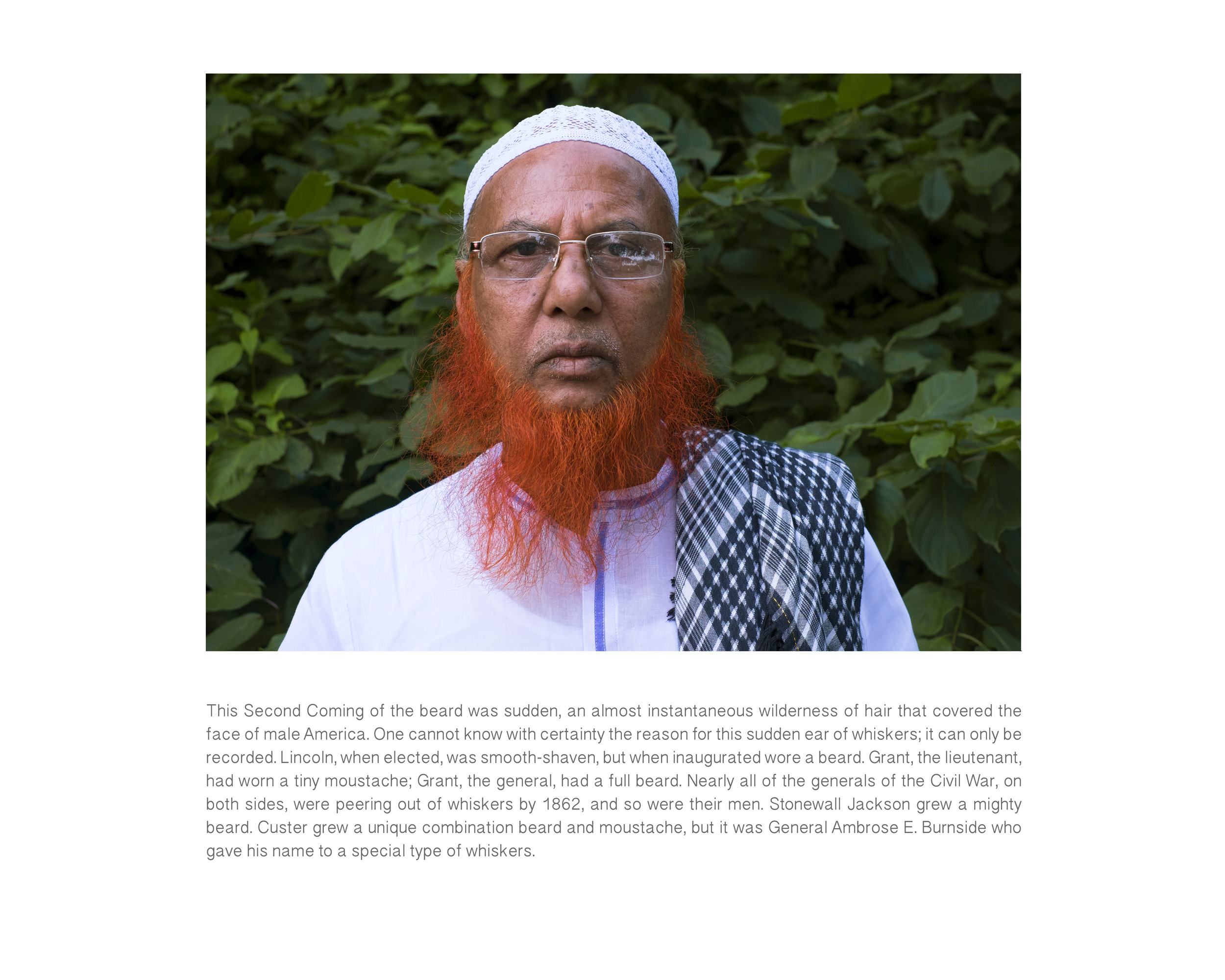

This Second Coming of the beard was sudden, an almost instantaneous wilderness of hair that covered the face of male America. One cannot know with certainty the reason for this sudden ear of whiskers; it can only be recorded. Lincoln, when elected, was smooth-shaven, but when inaugurated wore a beard. Grant, the lieutenant, had worn a tiny moustache; Grant, the general, had a full beard. Nearly all of the generals of the Civil War, on both sides, were peering out of whiskers by 1862, and so were their men. Stonewall Jackson grew a mighty beard. Custer grew a unique combination beard and moustache, but it was General Ambrose E. Burnside who gave his name to a special type of whiskers.

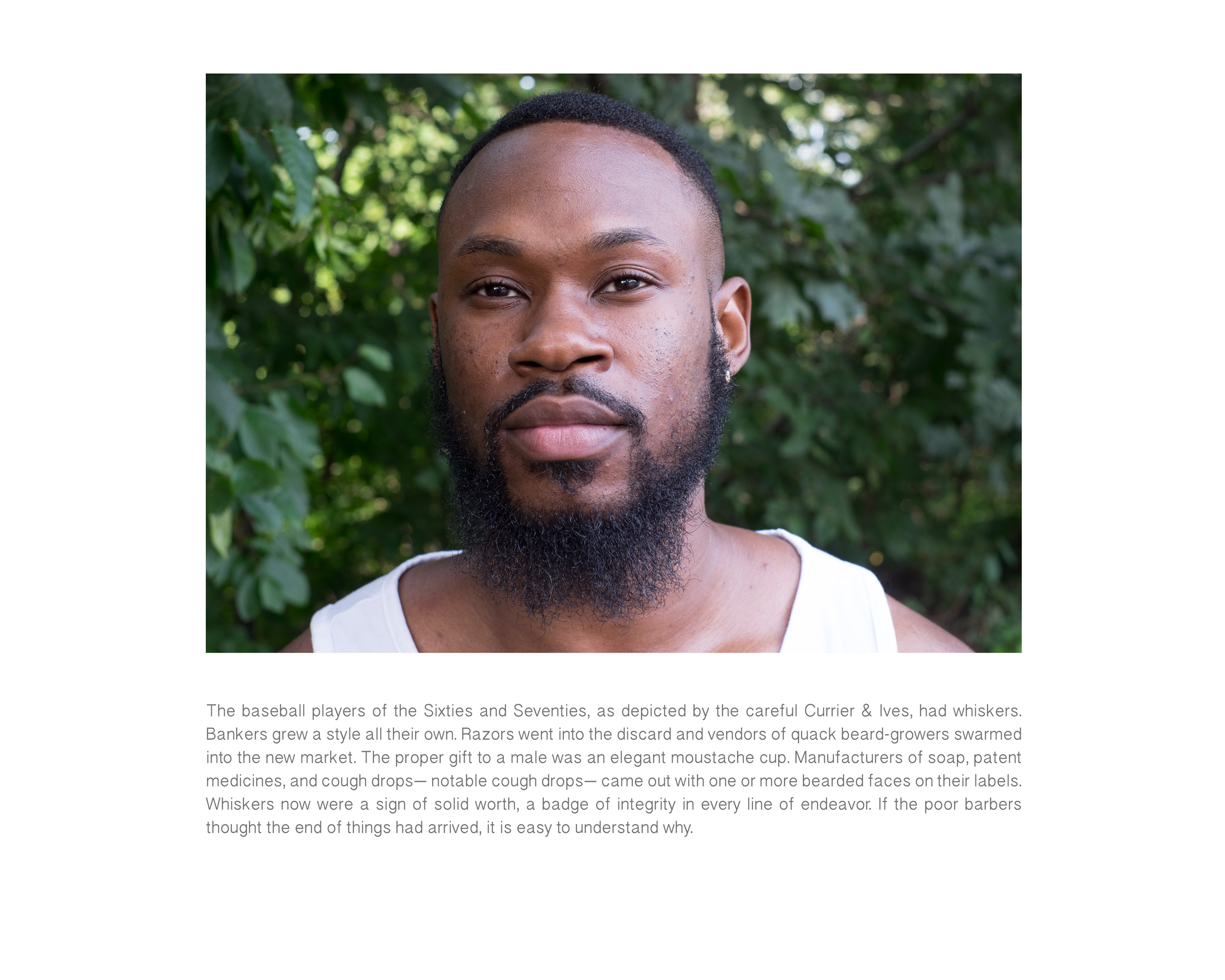

The baseball players of the Sixties and Seventies, as depicted by the careful Currier & Ives, had whiskers. Bankers grew a style all their own. Razors went into the discard and vendors of quack beard-growers swarmed into the new market. The proper gift to a male was an elegant moustache cup. Manufacturers of soap, patent medicines, and cough drops— notable cough drops— came out with one or more bearded faces on their labels. Whiskers now were a sign of solid worth, a badge of integrity in every line of endeavor. If the poor barbers thought the end of things had arrived, it is easy to understand why.

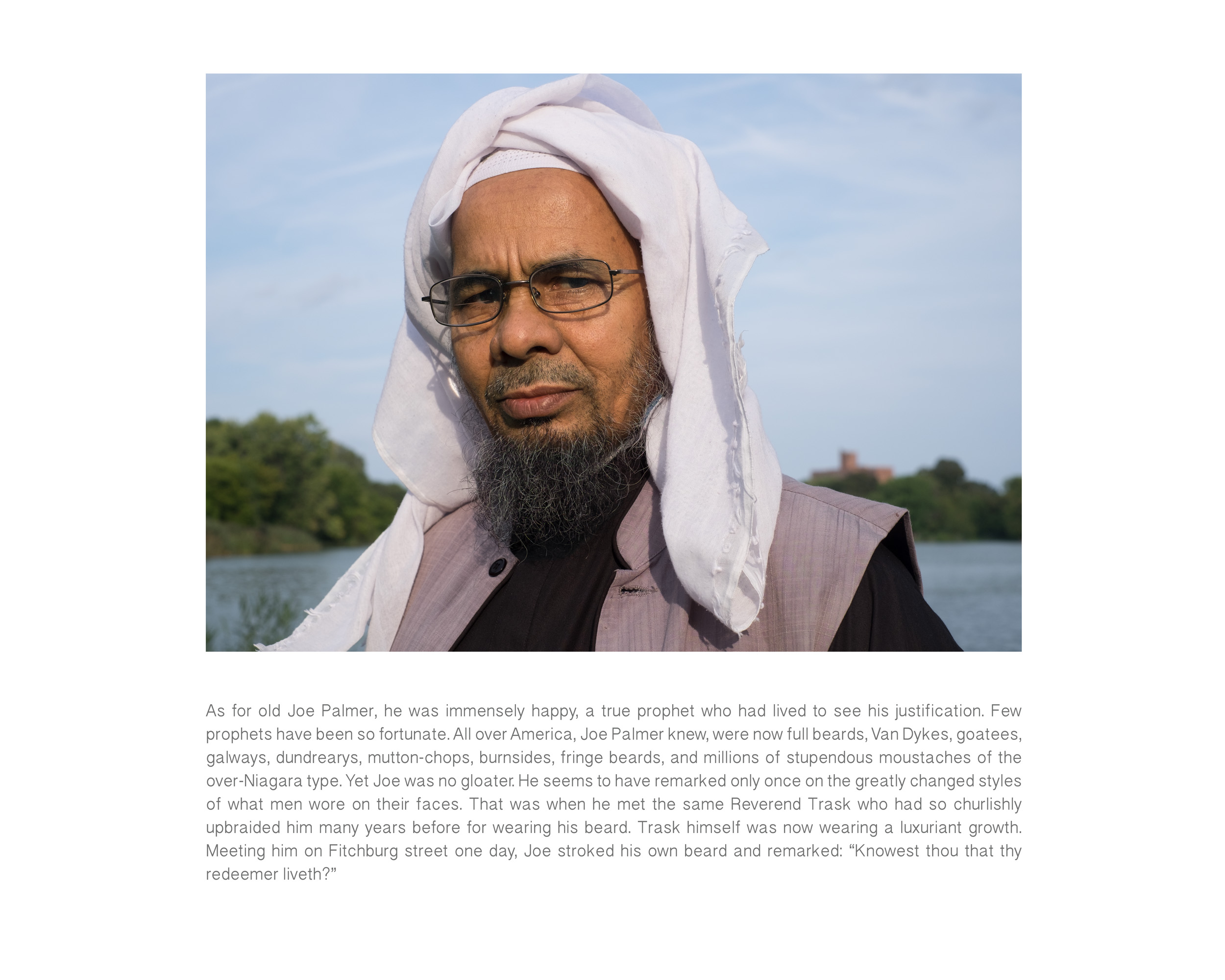

As for old Joe Palmer, he was immensely happy, a true prophet who had lived to see his justification. Few prophets have been so fortunate. All over America, Joe Palmer knew, were now full beards, Van Dykes, goatees, galways, dundrearys, mutton-chops, burnsides, fringe beards, and millions of stupendous moustaches of the over-Niagara type. Yet Joe was no gloater. He seems to have remarked only once on the greatly changed styles of what men wore on their faces. That was when he met the same Reverend Trask who had so churlishly upbraided him many years before for wearing his beard. Trask himself was now wearing a luxuriant growth. Meeting him on Fitchburg street one day, Joe stroked his own beard and remarked: “Knowest thou that thy redeemer liveth?”

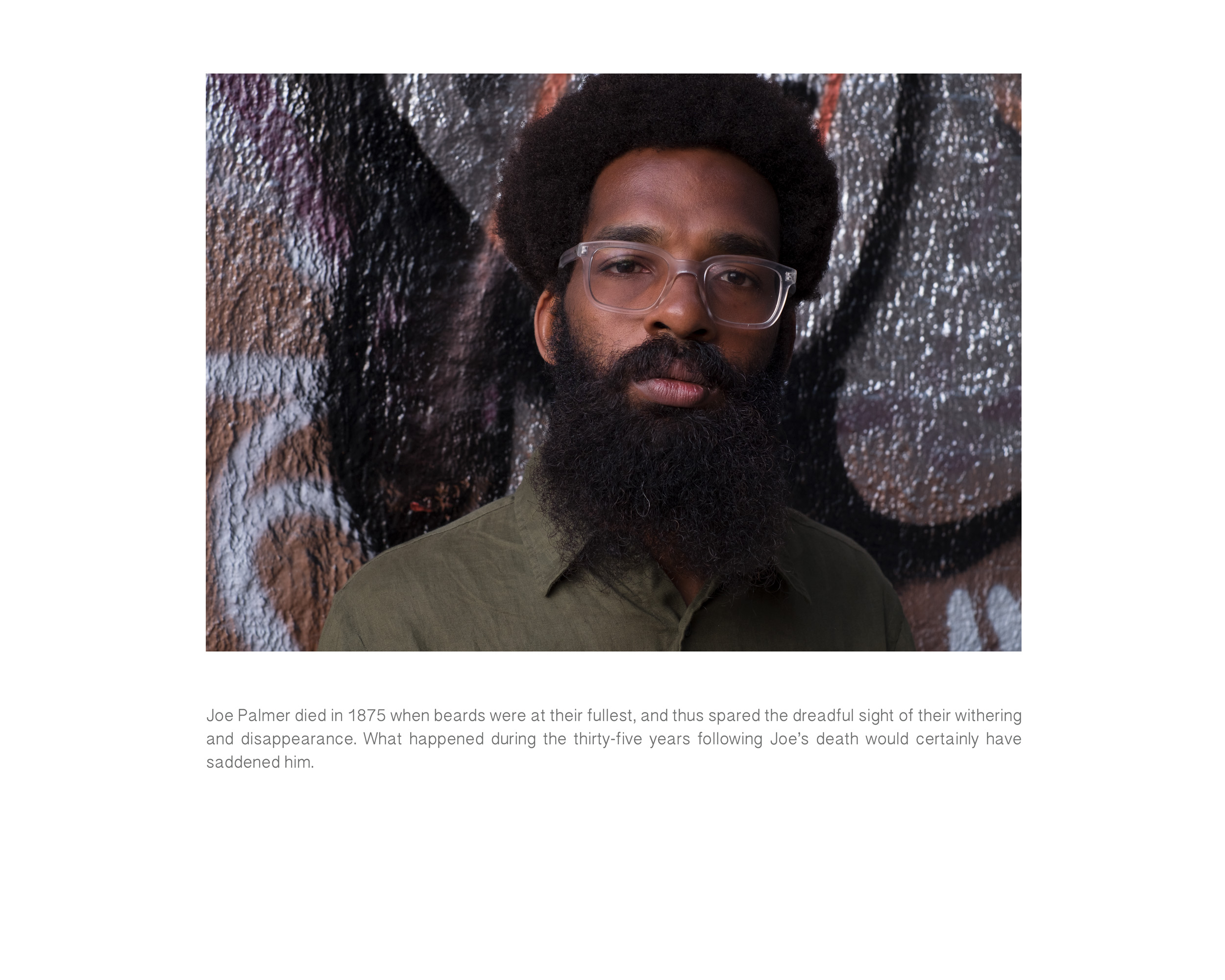

Joe Palmer died in 1875 when beards were at their fullest, and thus spared the dreadful sight of their withering and disappearance. What happened during the thirty-five years following Joe’s death would certainly have saddened him.

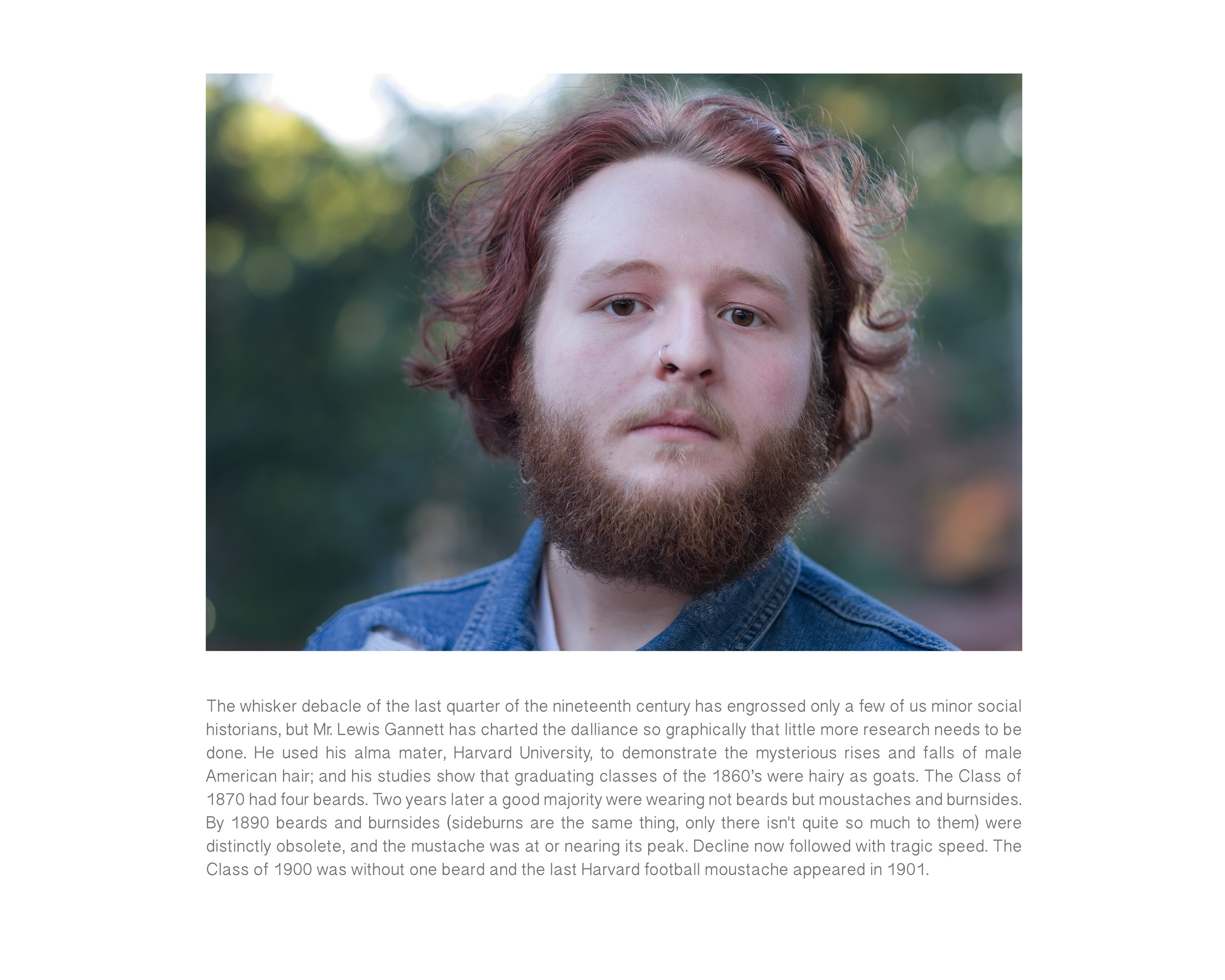

The whisker debacle of the last quarter of the nineteenth century has engrossed only a few of us minor social historians, but Mr. Lewis Gannett has charted the dalliance so graphically that little more research needs to be done. He used his alma mater, Harvard University, to demonstrate the mysterious rises and falls of male American hair; and his studies show that graduating classes of the 1860’s were hairy as goats. The Class of 1870 had four beards. Two years later a good majority were wearing not beards but moustaches and burnsides. By 1890 beards and burnsides (sideburns are the same thing, only there isn't quite so much to them) were distinctly obsolete, and the mustache was at or nearing its peak. Decline now followed with tragic speed. The Class of 1900 was without one beard and the last Harvard football moustache appeared in 1901.

The White House witnessed a similar decline of hair. From Lincoln to Wilson only one man without at least a moustache was elected to the Presidency. Grant had a beard, Hayes was positively hairy. Garfield fairly burgeoned with whiskers. Cleveland had a sizable moustache, Harrison a flowing beard, and both Theodore Roosevelt and Taft had moustaches. The lone smooth-shaven president during this entire period was McKinley.

Beginning with Wilson in 1912 and continuing to the present, no President has worn hair on his face. Many thought it was his beard that defeated Hughes, and his was for years the only honest beard to wag on the one heavily whiskered Supreme Court.

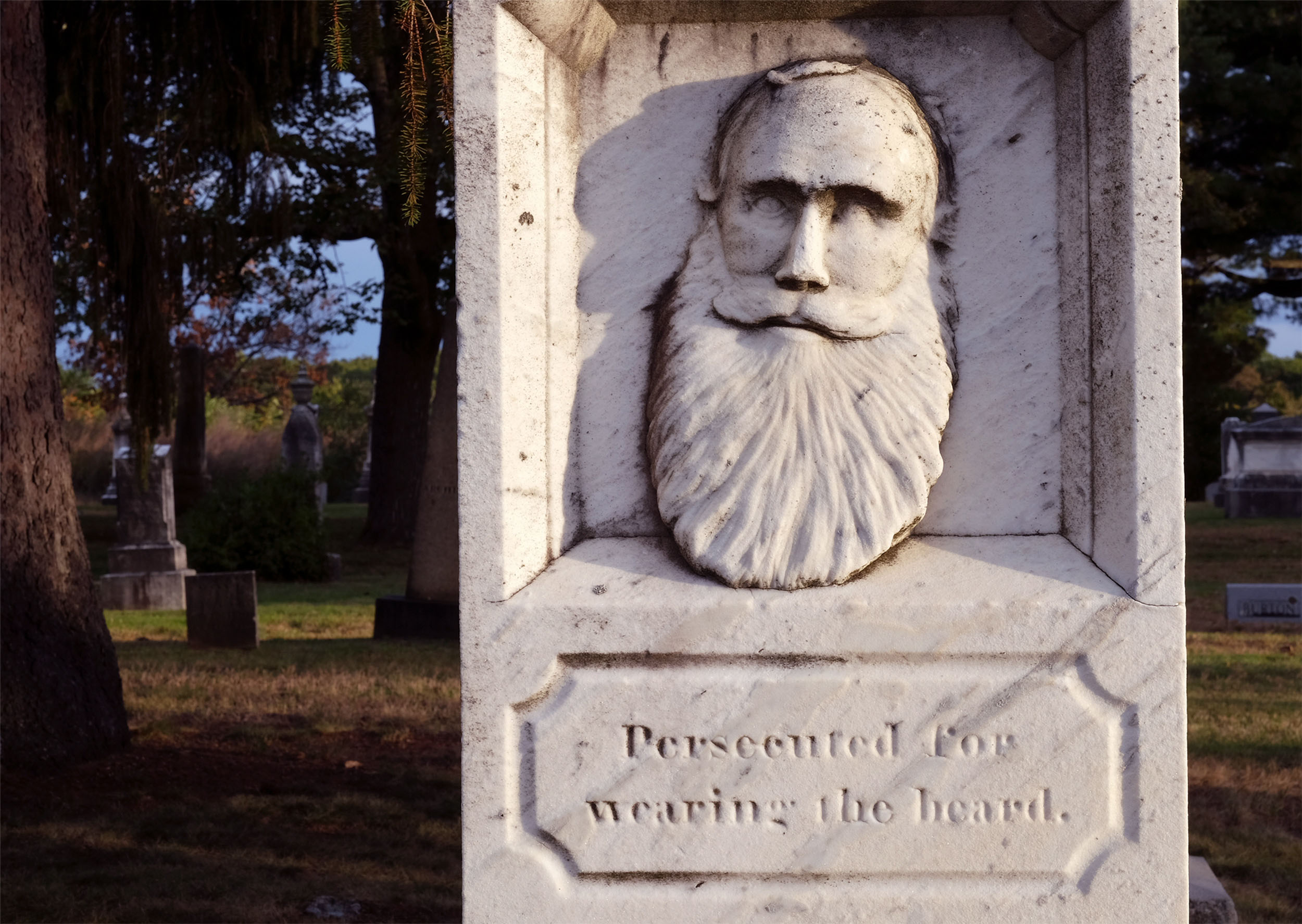

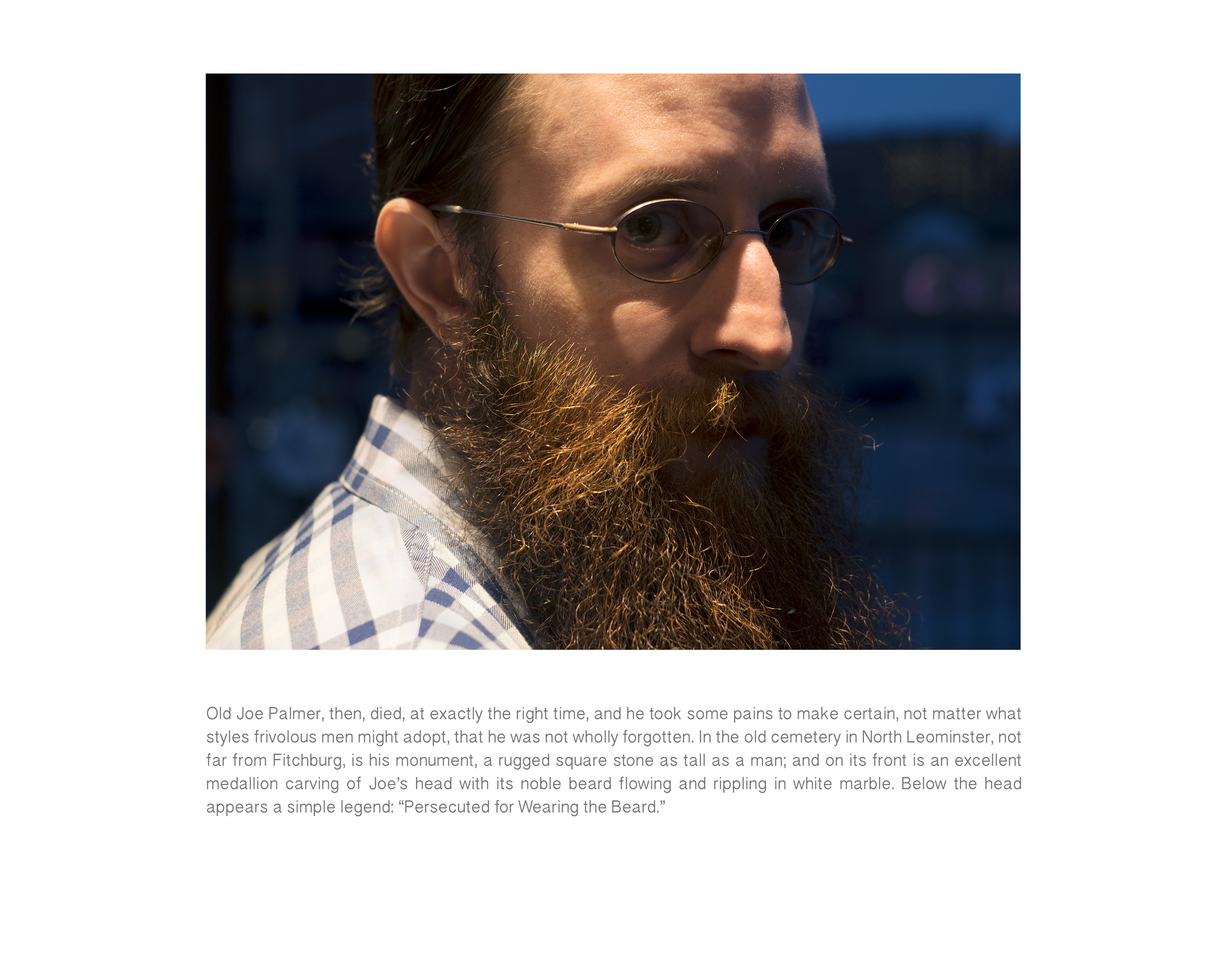

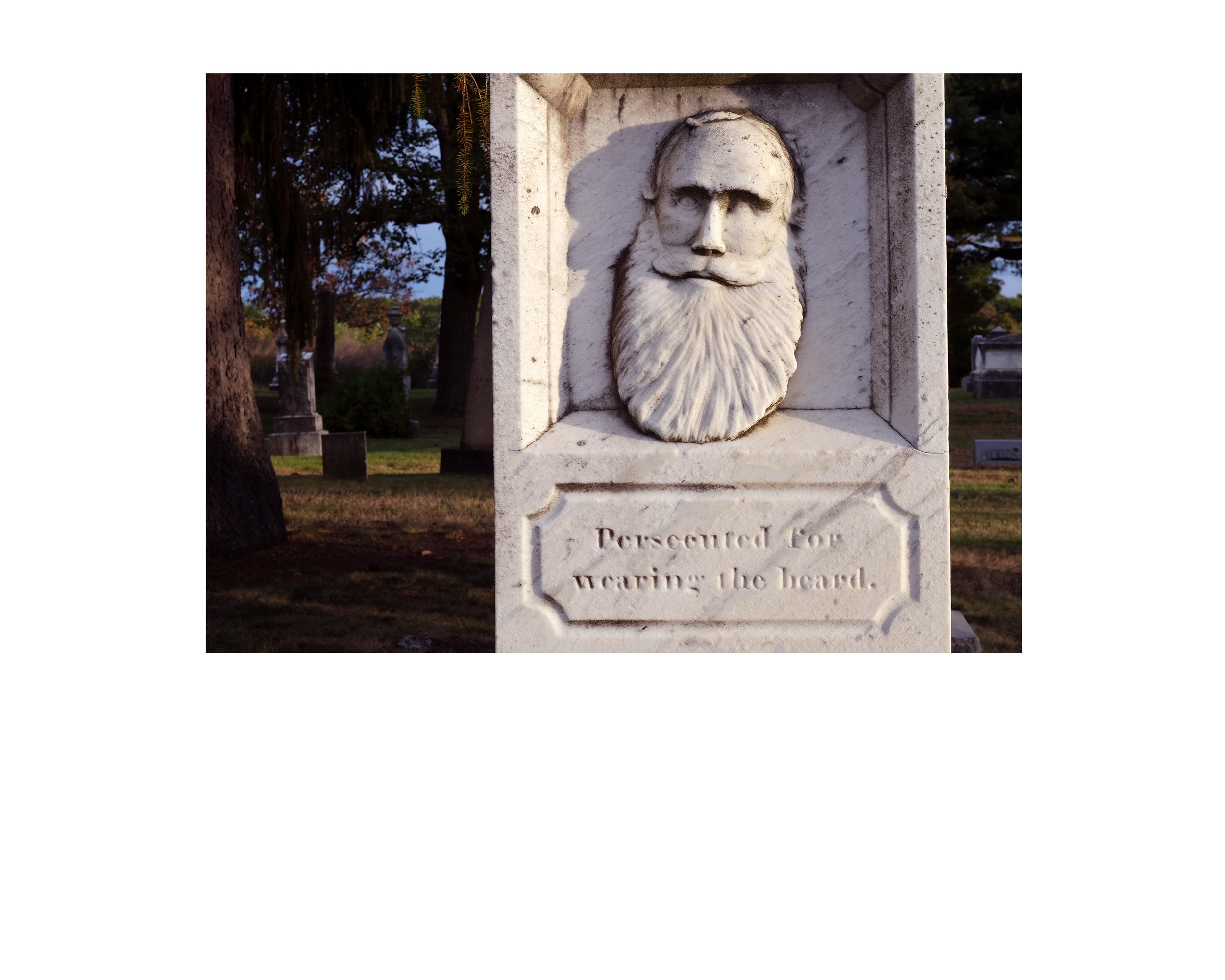

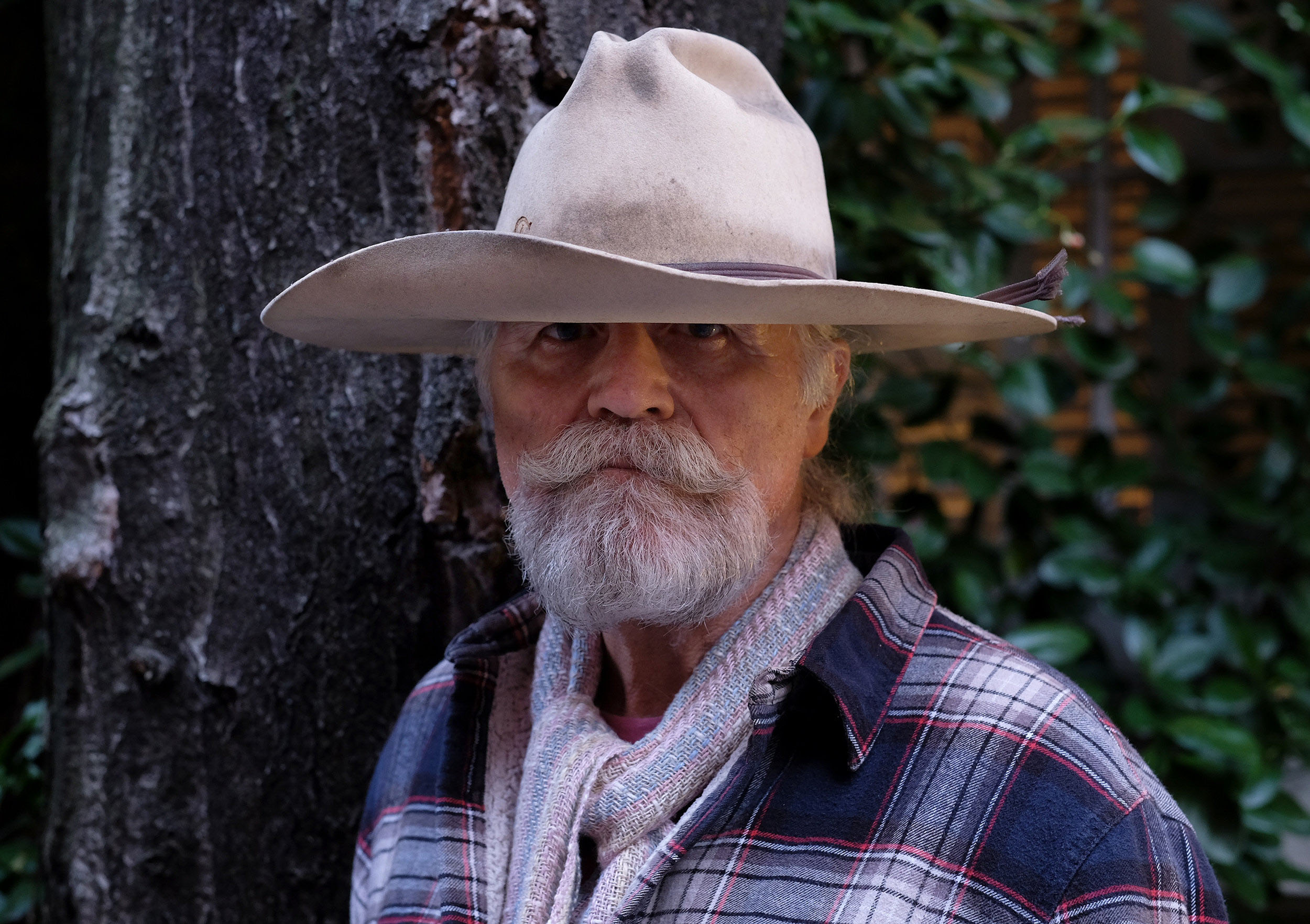

Old Joe Palmer, then, died, at exactly the right time, and he took some pains to make certain, no matter what styles frivolous men might adopt, that he was not wholly forgotten. In the old cemetery in North Leominster, not far from Fitchburg, is his monument, a rugged square stone as tall as a man; and on its front is an excellent medallion carving of Joe’s head with its noble beard flowing and rippling in white marble. Below the head appears a simple legend: “Persecuted for Wearing the Beard.”