Sweet Earth: Experimental Utopias in America

Earthships, invented by American architect M. K. Reynolds, derive their name from his idea of them as “independent vessels to sail on the seas of tomorrow.” They are generally made from tires filled with rammed earth, though sometimes of bottles and cans. They are often configured to maximize the surface area on which solar panels can be placed and typically have rain catchments and a filtration system for water (the circular object seen at the corner of the building is a cistern). Not visible in this photograph is an all-glass south facing wall. In the winter when the sun is low in the sky, sunlight pours through it directly into the home. The warmth that results is retained by the high insulating coefficient of the three earthen walls enabling the house to be sixty-eight degrees with minimal heating. In the summer, when the sun is overhead, the cool earthen walls maintain sixty-eight with little or no additional cooling. This home is sited so that on December twenty-first the sun is just over the horizon of the ridge to the east.

The house is one of numerous innovative structures that comprise Earthaven Ecovillage. Because Earthaven’s 320 acres are mostly mountainous forest, all dwellings are built on slopes, leaving flat ground available to become agricultural fields. Though still under construction, Earthaven has been completely off the grid since its inception in 1994. The central village is powered by a micro-hydro system and the water supply comes from a natural spring and is stored in a ten thousand-gallon water tank. Homes in the community are built of natural or recycled materials, and the entire site has been planned as a model of permaculture design.

Members pay annual dues, share title to the land and participate in a consensus decision-making process. Each community member is responsible for earning his or her own living. The village-scale economy includes numerous ecologically sound businesses, such as Red Moon Herbs and Permaculture Activist and Communities magazines.

The community doesn’t have a single village-wide spiritual practice. “What many of us have in common is a reverence for the Earth and our land, and the belief that our land is alive and conscious and it’s our sacred duty to honor and care for it.”

Hundreds of deaths occurred in Chicago in the 1990s because of heat waves. In response, the city of Chicago, in conjunction with the United States Environmental Protection Agency, initiated the City Hall Rooftop Garden Pilot Project, part of the Urban Heat Island Initiative.

Green roofs help minimize urban heat effect, which occurs in metropolitan areas when the sun bakes pavement and roof surfaces, raising temperatures to levels much higher than those of land surfaces in the countryside. A conventional rooftop can reach 140 degrees in summer, but when covered with a layer of soil and planted, it will tend to stay around 80 degrees, thus reducing the surrounding air temperature and the need for air conditioning within the building.

Numerous other benefits come from planted rooftops. They absorb up to fifty percent of the rain that falls on them, reducing the surge of water that can overload urban sewer systems during heavy downpours. They protect the underlying roof’s waterproofing layer from sun exposure, helping it to last forty or fifty years instead of the standard twenty.

Over one hundred building projects are now underway in the city, incorporating one million square feet of green roof. They are part of Mayor Richard M. Daley’s plan to transform Chicago into one of the greenest cities in the world.

When Stephen Gaskin, a charismatic philosopher from San Francisco, went on a speaking tour in 1970, his adherents followed him in buses and vans. After each engagement, a few more vehicles would follow along, until hundreds of people were in the caravan. Eventually, they bought two thousand acres of land in Tennessee and began living communally as the Farm.

They lived according to “Agreements,” including a personal and collective dedication to “harmlessness, right livelihood, right thinking, etc., while maintaining a sense of humor.” All members agreed to a vegan diet, nonviolence, a shared purse and voluntary poverty. Housing for the first several years consisted of used Army tents and the buses and vans in which they had traveled.

As the population steadily grew to fourteen hundred, the Farm gained self-sufficiency in food production and took on the aspect of an at-once primitive and technically advanced small town, dedicated to humane enterprise. Soybean farming and research led to commercial sales of soy products such as tofu, tempeh, soy yogurt and Ice Bean, an ice cream equivalent. When an earthquake devastated Guatemala, the Farm sent its charitable arm, Plenty, with carpenters and workers to aid in rebuilding; an ongoing relationship with communities in Central America resulted.

When municipal ambulance service in New York City’s South Bronx became unconscionably inadequate, the Farm began its own voluntary ambulance corps there.

As the Farm grew, Plenty expanded, and satellite farms in twenty states and foreign countries were founded. To stay in touch, a group of ham radio operators living at the Farm developed innovative space-based communications and an electronics manufacturing center, which helped serve the Farm’s broader environmental aims.

The Farm has developed solar hybrid vehicles, the doppler fetoscope (for amplifying the heartbeat of a young fetus), portable concentrating solar arrays and numerous other inventions, but the one device that has remained constantly in production and a financial success is the Nukebuster, a pocket-sized Geiger counter with a built-in alert system. After the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl disasters, sales of Nukebusters boomed. The resulting profits played a critical role in saving the Farm during a crisis in 1983, when crushing debt and a national recession nearly brought to an end to one of the most important alternative communities of the modern era.

Even though it has almost no rules or committees, Tolstoy Farm continues to be one of the longest surviving secular intentional communities in America. It was founded in 1963 when Huw “Piper” Williams returned to his home state of Washington from New England, where he was working as a peace activist and living on a communal farm. After purchasing some land, he invited his friends from the peace movement to join him in a “simple living kind of alternative Christian lifestyle.” Over the years those words have come to mean many things.

With one general meeting each year and weekly potlucks, the fifty members of Tolstoy Farm are happy to “associate and/or dissociate with each other freely.” The group has steadfastly adhered to a single founding principle: no one could be forced to leave, so “We would have to work out our differences in the right way.” At times the application of this rule has been tested in the extreme, but Tolstoy Farm remains a healthy, thriving commune.

For the past six seasons, a Community Supported Agriculture farm program (CSA) has prospered at the center of Tolstoy Farm. CSA programs are sometimes referred to as “subscription farming”: individuals pledge financial support to a farm operation before the growing season begins, so that both farmer and consumer share the risks and benefits of the crop. The CSA model is used by more than a thousand small farms in the US and Canada. A weekly box delivered to a subscriber of the Tolstoy Farm CSA in the month of September might contain corn, beets, carrots, chard, cucumbers, zucchini, kale, lettuce, potatoes, tomatoes, sweet and keeper onions, green peppers, pears, plums, winter squash, pumpkins, celery, tomatillos, garlic, hot peppers and green beans.

Tolstoy Farm takes its name from a historic settlement founded in 1910 outside of Johannesburg, South Africa, by Mahatma Gandhi as a base for passive resisters. In jail, Gandhi read Tolstoy—the Russian author’s renunciation of force as a means of opposition was formative to Ghandi’s political philosophy.

Twin Oaks was founded in 1967 by a group of people who had read about a fictional utopian community in B.F. Skinner’s novel, Walden Two. Skinner was a psychologist who taught at Harvard—at the heart of his book is a belief that scientific study and socially engineered rewards and punishments can change human behavior.

Behaviorism, as this idea was termed, was doomed from the start at Twin Oaks. Only three of the original eight founders were truly dedicated to creating a behaviorist community. More importantly, the commune was founded at the height of the hippie era—a moment in time far more given over to personal liberty and spontaneity than to behavioral control or the dominance of reason over emotion.

Moreover, the benefactor who made his land available to the commune stipulated that Twin Oaks must have a continuously increasing population to be in compliance with the lease. This provision forced the commune to accept new members regardless of their interest in the founding principles. After abandoning elemental behaviorism, except for the “planner-manager” decision-making model (a system of elected managers whose decisions may be overturned by a majority of the membership) and the labor-credit work system, Twin Oaks thrived and continues to do so today. Ninety adults and fifteen children (there is a quota for the number of children) live happily and well on the land, and their commitment to functioning as a model social system based on equality, income sharing and nonviolence remains unswerving.

Members work actively for peace, justice, ecology and fairness. Anthropologist Jon Wagner considers Twin Oaks to be “among the most non-sexist social systems in human history.” Each summer, the community hosts a women’s gathering, as well as the communities conference that has helped many other communes to successfully form and develop. Twin Oaks grows forty to sixty percent of its own food and is in the process of becoming an ecovillage. At present their collective income is derived from making and selling hammocks—Pier One Imports is the largest purchaser of them. They also manufacture and sell tofu and offer services in book indexing and web design.

Buildings at Twin Oaks are named after the great communes of the past, including Oneida, Harmony, Llano and Kaweah. With its long-term success and unwavering commitment to principles, Twin Oaks has proved itself the equal— and more—of its antecedents.

In 1971, four Philadelphians felt a need to change their lives. Instead of directly engaging in social and political activism they decided to, in their own words, “live ourselves into the future we seek.” Together with other urban exiles, they bought 280 acres in the Coastal Range of Oregon. On the property they found an old post office and took its name for their own: Alpha (the first letter of the Greek alphabet, alpha means “the beginning”).

Over the years, there have been thirty-five members (the community’s highest form of affiliation), nine of whom remain at Alpha today. Fifteen to twenty adults and children normally reside at the farm. They earn their collective living farming, doing rural mail delivery, through a cafe-bookstore (the Alpha Bit), and with a consulting practice that offers training in consensus formation.

All decisions at Alpha are made by consensus, a 350-year-old process established by the Quakers. It is based on the belief that each person has some part of the truth and no one has all of it. It is also based on the assumption that everyone is trustworthy (in Quaker consensus, a single person can block a decision if they believe it will cause harm). So the group must work to achieve unity: everyone must agree with the essence of a decision and then support it.

After twenty-five years of attending meetings, Caroline Estes, one of Alpha’s original members, accumulated such wide experience in consensus-based decision-making that her skills as a teacher and meeting facilitator have been in demand by organizations as diverse as Hewlett-Packard and the National Green Party.

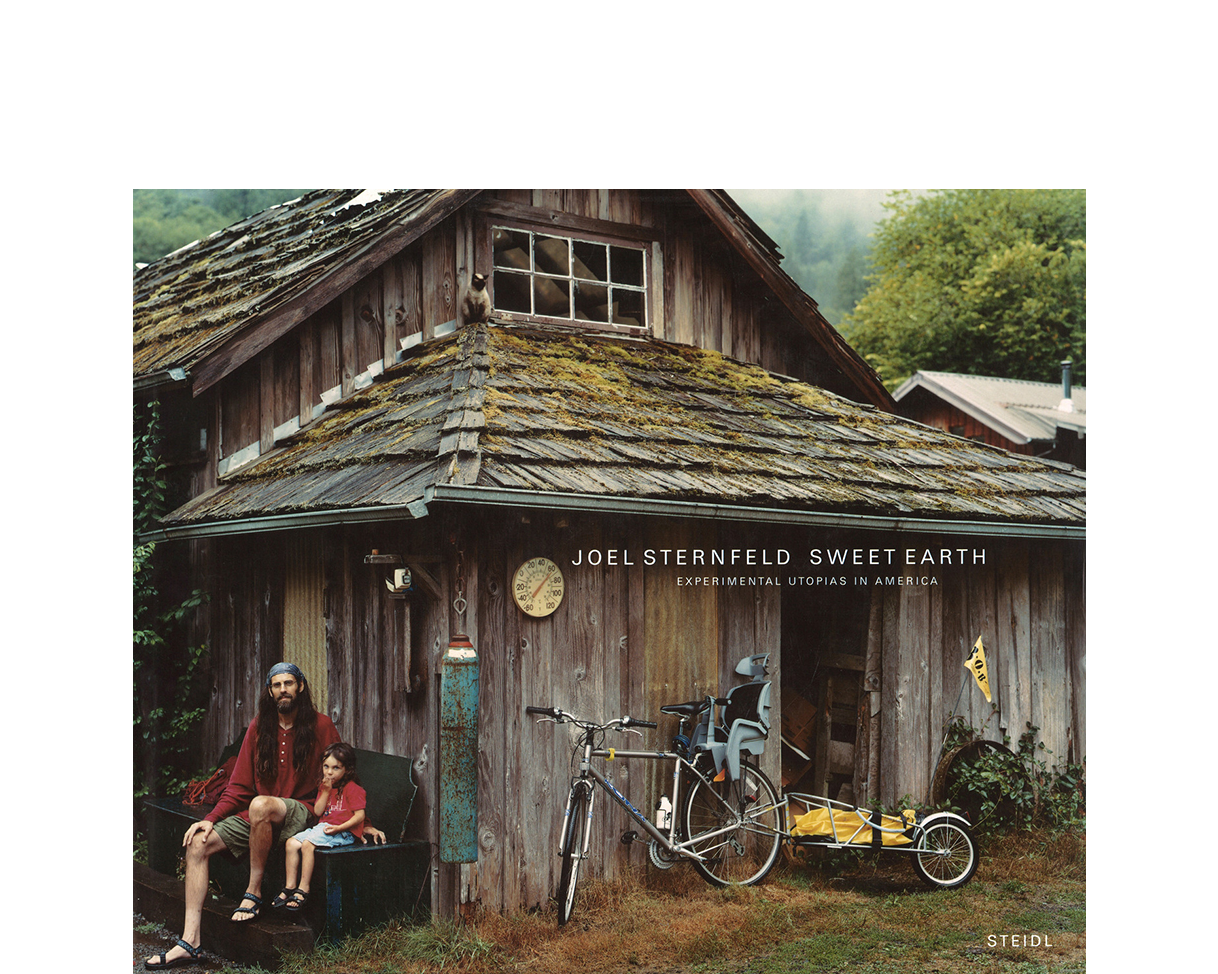

After the dissolution of his marriage, Jesse Johnson and his young son Gabriel biked 520 miles down the Oregon coast to join Alpha Farm. Also in the picture: Chaos, the cat.

George Rapp and his followers came to America in order to practice their religion free of governmental persecution. They left Germany and made their way to Southern Indiana, arriving in 1814.

Although their group was initially ravaged by malaria, they persevered and built a substantial town called Harmony. Relations with other communities were warm; the Harmonists gave financial assistance to other religious groups, and when they needed to make purchases, they did so from their co-communalists. But relations with distrustful neighbors proved highly problematic and, at times, violent. Particularly at issue was the Pentecostal Rappites’ commitment to celibacy. As Karl J. Arndt reports in America’s Communal Utopias,“ One Indianan wrote to the state general assembly, urging the outlawing of celibacy: ‘as there is many young Girls of Ex[c]elent Conduct and Beheavor in [H]armony And many young men of Good parts...it is shurly not Right that those who are man and wife should not Enjoy [each] other as such [just to] please the old gentleman.’”

In 1825, ongoing disputes with neighbors led the Rappites to sell Harmony to the socialist Robert Owen and to start over in Pennsylvania, where they built a new home, Economy. Once again they thrived, creating a community that in many respects, especially in its cultural and musical activities, resembled a European court. But the issues surrounding celibacy continued to trouble them, and this time the problems began to develop among the Rappites themselves. Some people, but not all, were allowed to elope and rejoin the community, and between 1826 and 1829, Rapp himself caused a major uproar because of his personal involvement with an unusually beautiful young woman, Hildegard Mutschler. He enraged many when he made her his personal assistant in alchemical experiments in search of the legendary “Philosopher's Stone,” said to turn base metals into gold.

Despite increasing wealth, continued insistence on celibacy diminished the Rappites' numbers. In 1916 the society was disbanded and what remained of its property went to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Old Economy became a state historic site, rented out, on occasion, for wedding receptions. The formal garden pictured was meant to evoke the Garden of Eden. Among its many symbolic representations is the statue of Harmony, depicted as “a woman clothed with the sun.”

Eretz HaChaim (Hebrew for “the living land”) is a kosher, organic communal farm, founded in 2002 by Ultra-Orthodox Jews under the leadership of Rabbi Chaim Adelman. The commune, still in formation as of this writing, owns seventy acres of land.

Following an early Jewish rule that presages modern sustainable farming practice, every seventh year they will let their land lie fallow. In accordance with the Torah, the “corners” of their fields will be left to the poor—if no poor show up to glean, the produce from the corners will be donated to charity. As Orthodox Jews they cannot milk cows on Saturdays, so gentiles will perform the task on that day. Their kosher organic chickens will not be fed grain during Passover. The community plans to be self-sufficient, with a synagogue, schools, a ritual bath and a swimming pool (the Talmud, a body of Torah interpretation, says that children must be taught to swim).

Eretz HaChaim is part of a larger return to a Jewish farming tradition. Sweet Whisper Farm in Readsboro, Vermont, specializes in organic education and maple syrup harvested using horse-drawn wagons. Mitzva Farms in Waukon, Iowa, produces Yetta’s Chedda, A Bis’l Swiss’l and Mazel Rella.

After losing his 1911 bid to become mayor of Los Angeles, Job Harriman, a prominent lawyer and a socialist of great conviction, founded Llano del Rio to demonstrate that socialism could work.

The site of a former temperance colony sixty miles northeast of Los Angeles was purchased for a down payment of fifteen dollars, and on May Day 1914 five families, five pigs, a team of horses and a cow came to Llano. Three years later, there were nine hundred residents. Conditions were harsh and demanding, yet the colony grew and prospered. Many members later recalled those years as the best, most exciting times of their lives. Freedom from capitalism, a varied social, intellectual and recreational life, and mass participation in the democratic process of the community gave Llano an Edenic quality.

The problems that undid the colony were internal dissension and an inadequate water supply. A group of dissidents, who met secretly at night in the surrounding sagebrush, deeply disrupted community discussion and debate. In fact, the “brushers” might have been saboteurs planted by Los Angeles Times publisher Harrison Gray Otis, who had opposed Harriman’s mayoral campaign and was known for his underhanded tactics.

When a conflict over water rights arose between the colony and neighboring citizens of the Big Rock Water District, Llano had to go to court over its right to irrigate. The opposing attorney referred to the group as “socialist plunderers,” and the case was lost. From that moment on, the failure of Llano was inevitable.

In 1918, a splinter group moved to a site in Louisiana, where they survived in a limited form for the next twenty years. In the 1940s, Aldous Huxley lived for a year in a house that had belonged to the original Antelope Valley colony—he wanted to absorb any remaining utopian karma.

Three of the original founders of Drop City met as art students in Lawrence, Kansas, in 1961. They referred to their practice of painting rocks and dropping them from a loft window onto the busy street below as “Drop Art.”

By 1965 the founders’ desire to live rent free and create art without the distraction of employment led them to a six acre goat pasture outside Trinidad, Colorado, which they purchased for $450. Naming their community after their gravity-driven art was the easy part; building it a little harder. But having recently attended a lecture by Buckminster Fuller and now joined by a would-be dome builder from Albuquerque, they began with scrap materials and visionary optimism. Sheet metal was stripped off car roofs (for which they paid a nickel or a dime) and attached to the grid of a dome. These building materials not only provided shelter, but they also emblemized the group’s refusal to participate in consumerist society. Money, clothing and cars were shared, and they lived as quasi-dumpster divers.

Initially the community flourished. With a core group of twelve, it functioned as the founders had intended, a hotbed of art- making. But a steady flow of publicity in underground and mainstream media, encouraged by resident Peter Rabbit, led to a torrent of guests. It has been reported that Bob Dylan, Timothy Leary and Jim Morrison visited, but the historian’s chestnut, the primary account, may be less than reliable when it comes to the 1960s. By the time the community decided to abandon its open-door policy, it was too late: the founding members had left, and conditions had taken hold that would bring about a final dissolution in 1973. In 1978 the site was sold; proceeds helped rent space in New York City for exhibitions of the group’s work and to publish it in Crisscross magazine.

The domes sat on the land of A. Blasi and Sons Trucking Company until recently, when they succumbed to gravity.

When Camp Dunlap, a World War II Marine training facility near Niland, California, was closed in 1946, all of the buildings were completely dismantled, leaving numerous cement foundation slabs in the desert.

Almost as soon as the government abandoned the site, “snowbirds” (campers from northern states in recreational vehicles) began to winter on the slabs, even though no running water, electricity or sewage facilities were available. Today at least five thousand snowbirds arrive each winter, and a few have become permanent year-round residents, despite summer temperatures that can reach 120 degrees. The snowbirds come with motor homes costing half a million dollars and they come with tents.

Over the years, a true self-governing community has arisen, including a mayor, the Slab City Christian Church (in a trailer), the Lizard Tree Library (used paperbacks on an honor system), the Gopher Flats Country Club (gravel greens), the Oasis Social Club (combination meeting space/junkyard), a CB radio station (one half hour of purely local news, nightly at six p.m.) and the Range, an outdoor nightclub built by “Builder Bill,” complete with stage, lighting, bar, communal outhouse and several rows of salvaged airliner seats. The Range takes its name from an active bombing range located a few miles away, which makes the sight and sound of F-16 sorties a part of life at the Slabs.

Moira, the Queen of the 2005 Prom at the Range, never got to go to her high school prom.

Curtis Howe “Doc” Springer called himself a physician and a Methodist minister, although he was neither. He created the name “Zzyzx” for the health resort he built in the Mojave Desert, hoping it would be the “last word” in resorts. Zzyzx was a Christian resort predicated upon a belief in the curative powers of its mineral waters—and the destructiveness of alcohol and arguing. Smoking, however, was acceptable everywhere but the dining room, bathhouse, sundeck and pool area (the prohibition in these areas related to concerns about the hazard of combining bare feet and burning cigarette butts).

The project began in 1944 when Springer filed a mining claim on an area of land eight miles long by three miles wide on the site of Hancock’s Redoubt, an 1860 army outpost. Using laborers from skid row in Los Angeles, whom he paid with food and showers, he built a hotel on the street he called the Boulevard of Dreams, an airport (Zyport), and a health spa that included a cross-shaped pool and a mechanical exercise horse that had been in the White House during the presidency of Calvin Coolidge.

Zzyzx also had a radio station from which Doc Springer’s nightly broadcasts were beamed to 221 radio stations in the US and 102 abroad. On the air Springer played religious music, preached his folksy religious philosophy, and sold his quack curative products: Hollywood Pep Tonic; Antediluvian Desert Tea, a peppermint herb brew; Zy-Pac, mineral salts from the bed of Lake Tuendae, which users were directed to rub on the scalp, then bend over and hold their breath as long as possible; and Mo-Hair, a purported baldness cure.

It was Mo-Hair that particularly incurred the ire of the American Medical Association and was instrumental in Springer’s 1969 arrest and sixty-day jail sentence. At the same time, the IRS, the FDA and the Bureau of Land Management began legal proceedings against him.

In 1974, Springer and a few hundred of his followers were ejected from Zzyzx, despite his willingness to pay the government $34,187 owed in back rent. He died in Las Vegas in 1986 at the age of ninety. Zzyzx is now referred to by its earliest name, Soda Springs, and is used as the Desert Studies Center of the California State University system. Lake Tuendae has been discovered to be the home of a tiny endangered fish, the Mojave Tui Chub.

This community of experimental fiberglass domes offers transitional housing for as many as thirty-four homeless people. Eight of the domes contain common facilities, including kitchens, bathrooms, laundries and computer rooms. The other twelve provide shelter for single individuals or families. Activist Ted Hayes founded the village in 1993 as alternative for the many homeless people who are afraid of shelters. The domes allow greater privacy for the people who stay in them, and the village itself acts as a microcosm of society, providing residents with a setting in which they may stabilize their lives and garner the skills necessary to reenter the “real world.”

With their distinctive design, the domes are meant to call the attention of passing motorists on the nearby Harbor Freeway to the problem of homelessness. Initial funding for Dome Village was provided by the Atlantic Richfield Oil Company.

Ted Hayes has a long history of promoting innovative ways to help the homeless that incorporate problem-solving and individual responsibility. He is sometimes referred to as the “Rasta Republican.” In the 1980s he started a cricket team made up of Latino teenagers and homeless men, “Homies and Popz.” The team has played at Windsor Castle and is the subject of a forty-minute operetta commissioned by the Los Angeles Opera.

Throughout the twentieth century, architects have been particularly ready to offer their visions of an idealized urban future. For Le Corbusier, a “Radiant City” would be appropriate to the machine age, providing a highly efficient and organized grid to facilitate modern life. For Frank Lloyd Wright, it was critical that everyone have their own patch of earth on which to realize their individuality: thus his “Broadacre City” not only necessitated personal land to live on, but a car to get there. The Italian-born architect Paolo Soleri is far less well-known to the public than Le Corbusier or Wright, but in the Arizona desert he is quietly building what is perhaps the world’s only true prototype of a futurist city.

Arcosanti is an “Arcology,” a word used by Soleri to describe the harmonious marriage of architecture and ecology. Unlike Wright, with whom he studied, Soleri believes that it is the physical dispersal in the landscape permitted by the automobile that has led to moral and spiritual dispersal in society. By contrast, Arcosanti, planned for five thousand inhabitants, will occupy only two percent of the land normally taken up by a suburban development. Residents work no more than a ten-minute walk from their homes, eliminating the need for cars within the city—consistent with Soleri’s prophecy of the eventual extinction of the automobile. Reminiscent of the historic center of Italian cities, every aspect of Arcosanti’s design, including numerous balconies, terraces and piazzas, encourages a maximum of social interaction.

Soleri is also critical of excessive consumption of resources. To avoid wasting materials, gardens, solar heating and natural cooling move the community toward self-sufficiency.

Arcosanti has been under construction for thirty-five years, self-funded by the sale of distinctive wind chimes and bells that are forged on site. It is being built by students and volunteers—progress is at once achingly slow and surprisingly fast. Visitors will find a substantial and unusual small community of about fifty permanent residents, and significant glimpses of a city that feels ancient and futuristic as it rises.

The home of Giles Blunden is independent of the public power grid. The solar panels visible on his roof provide electricity and heat water. Blunden is the chief architect and founder of Arcadia Homes, a sustainable cohousing community in which all thirty-three residences have passive solar design (non-mechanical solar heating achieved through site selection and large south-facing windows) and some active solar elements (collecting the sun’s rays by appropriate technology to provide heat, mechanical power or electricity).

In addition to its solar features, Arcadia is a pedestrian-friendly community that preserved nine acres of climax hardwood forest when it was built, by clustering houses on land covered with secondary- growth pine trees. The distinctive architecture of the community derives from vernacular local millhouse structures.

In 2003 the share of all electricity produced by solar cell technology in the US was 0.07 percent—though as far back as 1979 President Jimmy Carter announced (at a press conference held on the White House roof) the goal of bringing sun, wind and other renewable resources-generated electricity to twenty percent of the US total by the year 2000. In contrast, Japan, where fossil fuels are much more expensive, generated four times the amount of solar electricity produced in the US.

As solar power approaches a cost of $2 per watt, it is becoming less expensive than commercial power. Thirty-eight states, including North Carolina, have enacted “net metering” laws that require utilities to connect residential solar panels into the grid and to compensate homeowners for any excess electricity they produce.

The eight founders of Springtree first met at a Twin Oaks community conference in 1971. They all had children and wanted to build a community centered around them. By pooling their resources, they were able to purchase one hundred acres along the Hardnose River in Virginia, naming their new home for the old poplar tree that stood at the head of a clear spring. Each year, the founding of the community is celebrated there.

At its peak, Springtree was home to fifteen adults and fifteen children. It was, and still is, a close-knit intentional community in which ownership of land, homes and income is shared equally—a single checkbook still serves all. There is no leader or hierarchy. As a group they have never had an ambition for larger social change or commercial success, focusing instead on living well together (some might say their way of life is social change). Home schooling was a key element, and each child had an adult read with him or her nightly.

Not only did the group initially live together in the large house that they built, they also vacationed together. They drove by school bus to the outer banks of North Carolina and camped. The annual trip to the beach now functions as a reunion for Springtree members, their children and grandchildren.

Time and change have slowly eroded the community’s numbers—two couples and an occasional intern live at Springtree today, sharing meals and conversation, and working in the garden and orchards together. An extensive calendar of visits from and to the world at large often interrupts the routine of farm work.

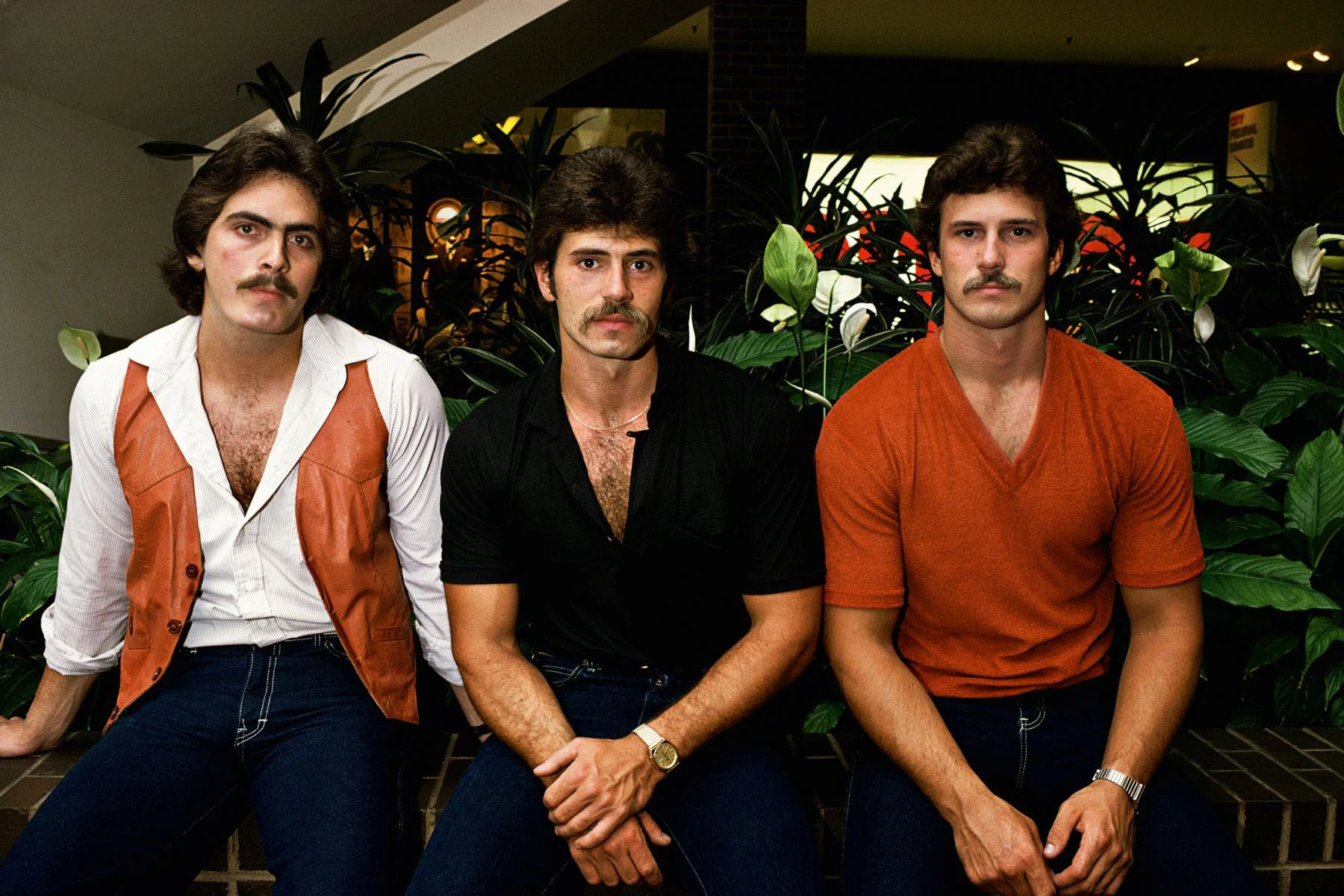

Asked what she was thinking when this group portrait was made, Ruth Klippstein responded, “Though I’m not very smiley in the picture, I imagine I was thinking the main thoughts that make me happy: this is my place, these are my people. It’s great to be rooted.”