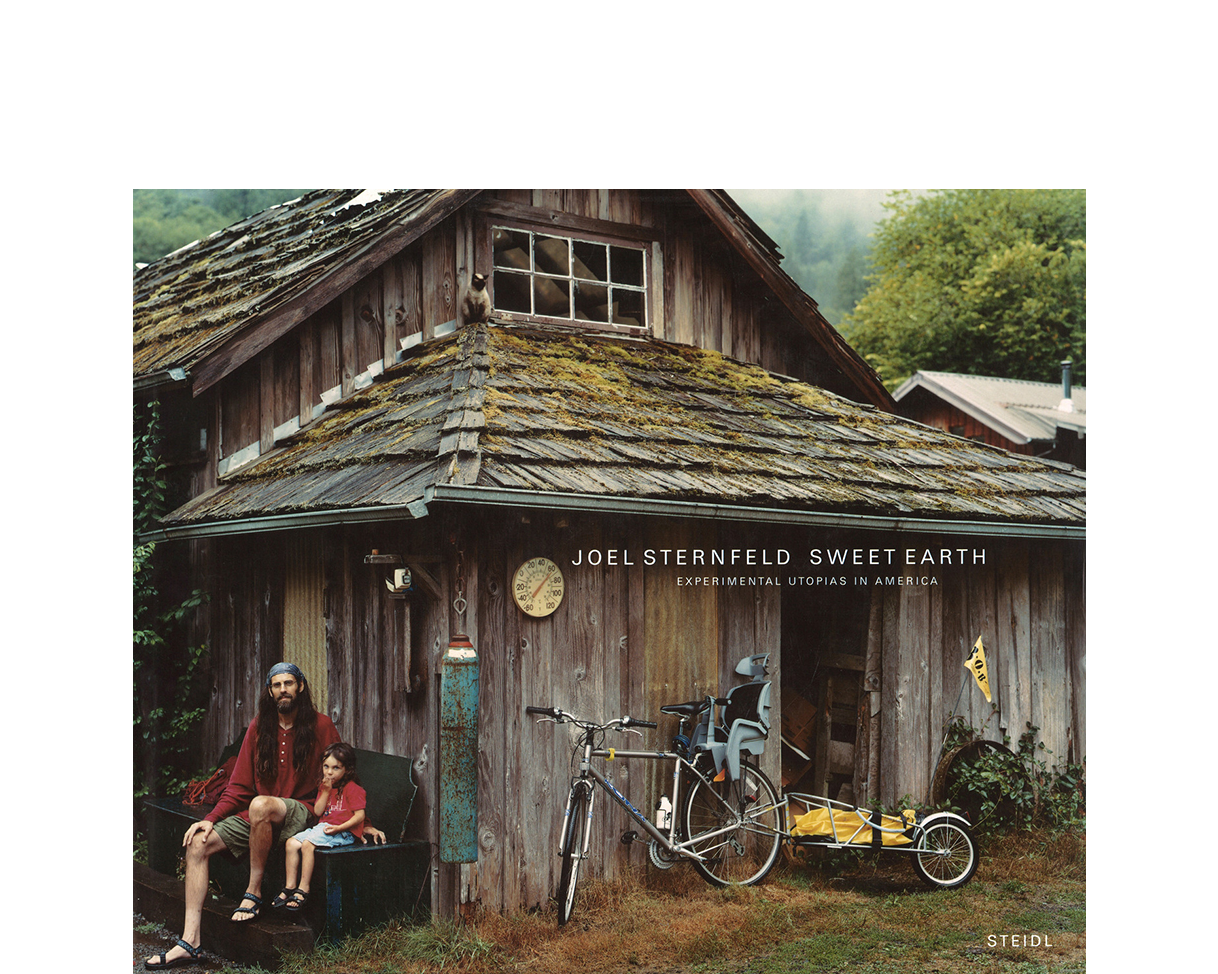

Sweet Earth: Experimental Utopias in America

Book images and full captions

The General Sherman Tree, Sequoia National Park, California, January 1994.

In the 1880s the Kaweah Cooperative Commonwealth, a socialist organization in San Francisco, acquired the homesteading rights to a large tract of land in the High Sierras. The initiator of the group was a powerful labor organizer Burnette G. Haskell. His friends who had joined him in hope of creating a new society based on cooperation were primarily sea men and intellectuals. They spent years debating about their land’s development.

Finally in 1885 they decided that they would harvest and sell lumber. Three hundred members boarded railroad cars and traveled south to Kaweah. They spent four difficult and wonderful years building a logging road on which they hoped to carry giant redwoods down from altitudes of eight thousand feet. Eighteen miles of granite ledges had to be hewn by pick and shovel in order to complete it.

Building the road was not the only treacherous obstacle the group faced: railroad companies, lumber interests and conservative newspapers missed no opportunity to attack in print both Kaweah and the socialist threat it presented. Just when the logging road and the dream of a steady means of support for their community was nearing completion, the US Congress created Sequoia National Park and took their land. The tree the colonists had called the Karl Marx tree officially became the General Sherman tree.

In creating this park, Congress may not have been acting out of a pure interest in wilderness preservation. By then the importance of tree cover in the mountains in maintaining the watershed was well known to farming interests in the San Joaquin Valley below.

Though the road they built provided the only access to the High Sierras for many years to come, the Kaweah Cooperative was never compensated for building it.

Acorn Community, Mineral, Virginia, April 2004

Acorn is a young, struggling community. A 1993 offshoot of the paradigmatic Twin Oaks Community, it lies seven miles down the road—or river, which is sometimes canoed. In the early 1990s, a surge of interest in intentional communities saw the population of Twin Oaks outgrow its own infrastructure; in response Acorn was established on seventy-five beautiful acres of farmland. Membership has fluctuated over the years and currently numbers about thirteen.

Acorn defines itself as “a young community seeking ways of living that are cooperative, caring and ecologically sustainable.” The members work in exchange for coverage of basic needs such as housing and food. The community supports itself with tinnery crafts (rainbow lights, double-hanging candleholders and hanging planters, which can be viewed on www.communitymade.com) and the Southern Exposure Seed Exchange, which is referred to as “our beloved seed business.” Southern Exposure is a company passionately committed to heirloom varieties and “open-pollinated” varieties of vegetables, herbs and flowers. It has taken as its mission the preservation and distribution of rare and endangered plant species and the education of growers and the public about the importance of saving seeds.

Southern Exposure points out that prior to World War II, vegetables and flowers were grown by farmers who chose and saved seeds suitable for the local microclimate and soil. During the war, however, a concerted effort was made to ship food to Europe, and afterward California and Florida became factories for produce that was selected for its ease of shipping, uniform ripeness and ability to perform well in a chemical environment.

Southern Exposure specializes in heirloom seeds that were chosen over the course of years by local growers, but their efforts are threatened by genetically modified plants. The only way to protect heirloom and rare varieties from being pollinated by GMOs is to keep them distanced from these new creations. Unfortunately, GMOs have a twenty-times greater outcrossing (pollen fertility) rate than non-GMOs; as a consequence, Southern Exposure never knows if its plants grown for seed will be safe.

So, like Acorn itself, Southern Exposure Seed Exchange is struggling for its existence.

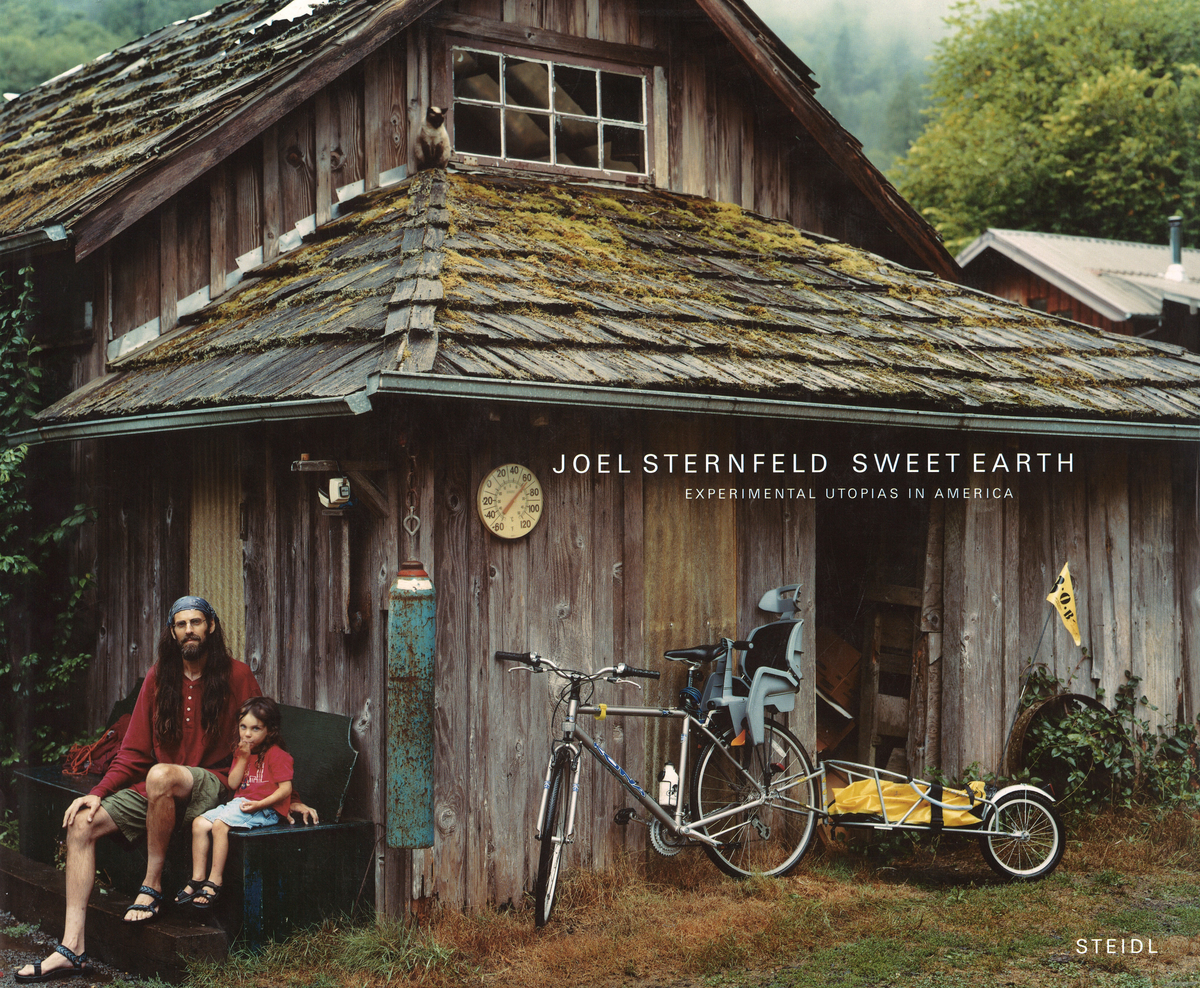

Alpha Farm, Deadwood, Oregon, August 2004

In 1971, four Philadelphians felt a need to change their lives. Instead of directly engaging in social and political activism they decided to, in their own words, “live ourselves into the future we seek.” Together with other urban exiles, they bought 280 acres in the Coastal Range of Oregon. On the property they found an old post office and took its name for their own: Alpha (the first letter of the Greek alphabet, alpha means “the beginning”).

Over the years, there have been thirty-five members (the community’s highest form of affiliation), of whom nine remain at Alpha today. Fifteen to twenty adults and children normally reside at the farm. They earn their collective living farming, doing rural mail delivery, through a cafe-bookstore (the Alpha Bit), and with a consulting practice that offers training in consensus formation.

All decisions at Alpha are made by consensus, a 350-year-old process established by the Quakers. It is based on the belief that each person has some part of the truth and no one has all of it. It is also based on the assumption that everyone is trustworthy (in Quaker consensus, a single person can block a decision if they believe it will cause harm). So the group must work to achieve unity: everyone must agree with the essence of a decision and then support it.

After twenty-five years of attending meetings, Caroline Estes, one of Alpha’s original members, accumulated such wide experience in consensus-based decision-making that her skills as a teacher and meeting facilitator have been in demand by organizations as diverse as Hewlett-Packard and the National Green Party.

After the dissolution of his marriage, Jesse Johnson and his young son Gabriel biked 520 miles down the Oregon coast to join Alpha Farm. Also in the picture: Chaos, the cat.

Arcadia Cohousing, Carrboro, North Carolina, April 2005.

The home of Giles Blunden is independent of the public power grid. The solar panels visible on his roof provide electricity and heat water. Blunden is the chief architect and founder of Arcadia Homes, a sustainable cohousing community in which all thirty-three residences have passive solar design (non-mechanical solar heating achieved through site selection and large south-facing windows) and some active solar elements (collecting the sun’s rays by appropriate technology to provide heat, mechanical power or electricity).

In addition to its solar features, Arcadia is a pedestrian-friendly community that preserved nine acres of climax hardwood forest when it was built by clustering houses on land covered with secondary-growth pine trees. The distinctive architecture of the community derives from vernacular local millhouse structures.

In 2003 the share of all electricity produced by solar cell technology in the US was 0.07 percent—even though as far back as 1979 President Jimmy Carter announced the intention (at a press conference held on the White House roof) to bring sun, wind and other renewable resources-generated electricity to 20 percent of the US total by the year 2000. In contrast, Japan, where fossil fuels are much more expensive, generated four times the amount of solar electricity produced in the US.

As solar power approaches a cost of $2 per watt, it is becoming less expensive than commercial power. Thirty-eight states, including North Carolina, have enacted “net metering” laws that require utilities to connect residential solar panels into the grid and to compensate homeowners for any excess electricity they produce.

Paolo Soleri at Arcosanti, Cordes Junction, Arizona, August 2000.

Throughout the twentieth century, architects have been particularly ready to offer their visions of an idealized urban future. For Le Corbusier, a “Radiant City” would be appropriate to the machine age, providing a highly efficient and organized grid that would facilitate modern life. For Frank Lloyd Wright, it was critical that everyone have their own patch of earth on which to realize their individuality: thus his “Broadacre City” not only necessitated personal land to live on, but a car to get there. The Italian-born architect Paolo Soleri is far less well-known to the public than Le Corbusier or Wright, but in the Arizona desert he is quietly building what is perhaps the world’s only true prototype of a futurist city.

Arcosanti is an “Arcology,” a word used by Soleri to describe the harmonious marriage of architecture and ecology. Unlike Wright, with whom he studied, Soleri believes that it is the physical dispersal in the landscape permitted by the automobile that has led to moral and spiritual dispersal in society. By contrast, Arcosanti, planned for 5000 inhabitants, will occupy only two percent of the land normally taken up by a suburban development. Residents work no more than a ten-minute walk from their homes, eliminating the need for cars within the city—consistent with Soleri’s prophecy of the eventual extinction of the automobile. Reminiscent of the historic center of Italian cities, every aspect of Arcosanti’s design, including numerous balconies, terraces and piazzas, encourages a maximum of social interaction.

Soleri is also critical of excessive consumption of resources. To avoid wasting materials, gardens, solar heating and natural cooling move the community toward self-sufficiency.

Arcosanti has been under construction for thirty-five years, self-funded by the sale of distinctive wind chimes and bells that are forged on site. It is being built by students and volunteers—progress is at once achingly slow and surprisingly fast. Visitors will find a substantial and unusual small community of about fifty permanent residents, and significant glimpses of a city that feels ancient and futuristic as it rises.

Daily Menu, Biosphere 2, Oracle, Arizona, July 2000.

Biosphere 2 was built to serve as a model for a human colony on the moon or Mars. Its $150 million cost was bankrolled by Texas oil billionaire Edward P. Bass. His partner in thought, John Allen, also known as Johnny Dolphin, was a new age visionary with a Harvard MBA, whom he had met at a Santa Fe commune after dropping out of Yale.

Biosphere 2 is a 7.2-million-square-foot facility that includes seven distinct biomes: a human habitat, a tropical rainforest, a savanna, a marsh, a desert and a million-gallon ocean.

Before moving into the biosphere, eight crew members (four men and four women) traveled the world to collect thirtyeight hundred species of plants and animals to inhabit the experiment, including a small lemur-like creature called a galagos, suggested by Mr. Allen’s friend William S. Burroughs.

Unfortunately 1991, the year that the Biospherians were sealed inside the dome for their two-year stay, coincided with an El Niño effect, an eastward shifting of warm Pacific Ocean waters that causes an increase in storm activity over the US Gulf states. The reduced sunshine slowed photosynthesis in the Biosphere’s oxygen-generating plants. When hummingbirds and bees began to die, plants were not pollinated and expected crops were not produced. The pigs raided the vegetable garden until they, too, died. Screeching galagos kept the Biospherians awake at night. Chickens laid only 256 eggs the first year. It wasn’t until they were fed a richer diet of cockroaches, which were ubiquitous, that they produce more.

The Biospherians lost significant amounts of weight, and oxygen levels in the domes began to dip to a point that made it difficult for them to complete daily tasks. Oxygen was secretly pumped into the facility—a transgression that irretrievably tarnished the project’s credibility.

As conditions worsened in Biosphere 2, tensions mounted among the crew. On the first anniversary of the experiment, Jane Goodall visited to observe the inhabitants. Allegations of food hoarding and food stealing abounded, and the Biospherians had splintered into two antagonistic camps. Though most had televisions in their apartments, they reportedly found it too torturous to watch them because of McDonald’s advertisements.

Following the unhappy dissolution of the first experiment, a second one was initiated, only to be terminated after six months.

The term “biosphere” was coined by Russian scientist Vladimir Vernadsky in 1929. It means the living sphere in which life survives. Biosphere 2 is so named because the original biosphere is the Earth itself. Biosphere 2 is currently for sale.

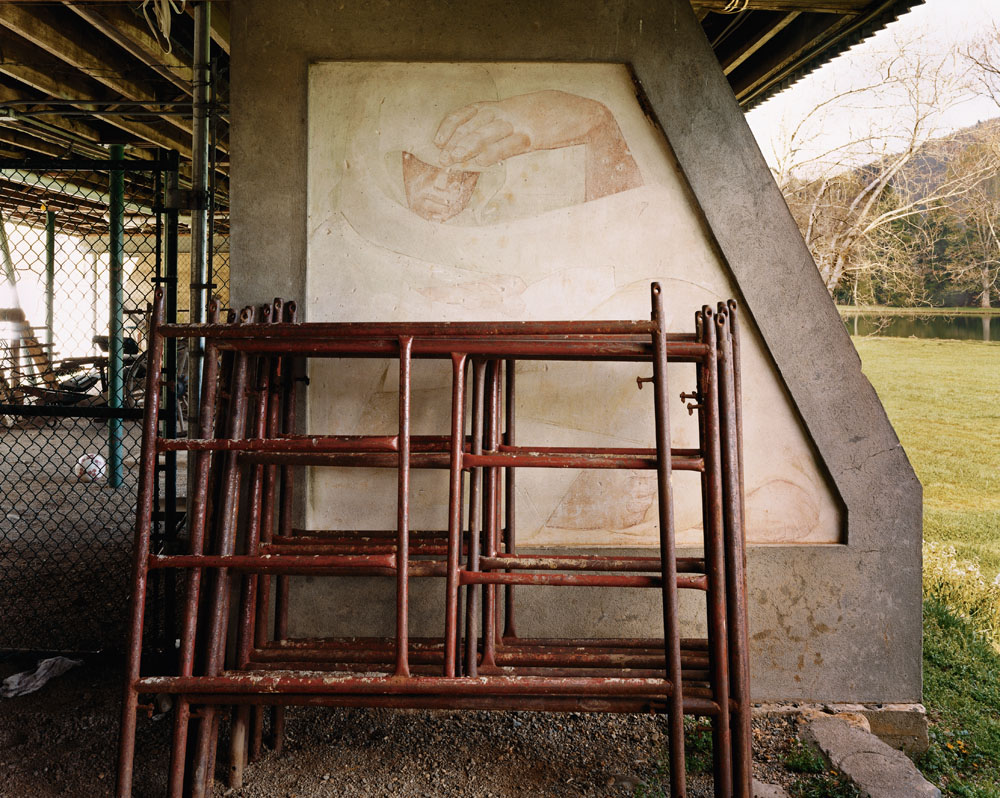

“Learning” by Jean Charlot, Camp Rockmount, Black Mountain, North Carolina, April 2005.

Black Mountain College was an experiment in communal education. During its 23-year history, from 1933 to 1956, small, informal classes and the spontaneous continuation of dialogue into the dining room and evening hours redefined boundaries between teacher and student. Black Mountain was a remarkable example of innovated higher education in its time. It didn’t have a traditional grading system–instead students were rigorously examined prior certification.

The organization and curriculum of the college were based on John Rice’s educational theories, which combined the liberal arts with the fine arts. It was the sixteen-year presence of Joseph Albers that was central to Black Mountain’s inordinate influence on modern art. Among his students were Robert Rauschenberg and Willem de Kooning. Other distinguished teachers included collaborators John Cage and Merce Cunningham. Buckminster Fuller taught engineering and built the first large-scale geodesic dome there with his students.

The mural “Learning” is one of two created by Jean Charlot in 1944 for the concrete pylons of the Walter Gropius-designed Studies Building. When Black Mountain College closed in 1956, it was sold to Camp Rockmount, a Christian boys’ camp. “Learning” and its sister mural “Inspiration” now enoble soccer and weightlifting equipment

Elias Rive at Camphill Village, USA, Copake, New York, June 2005.

Elias Rive’s day begins at 5:45 in the morning, when he walks out to the fields to bring the cows back to the barn for milking. The process is repeated each afternoon as part of the daily rituals of farming life at Camphill Village. Elias is one of roughly 240 adults who live in small extended-family households in this 600-acre community of farmland, gardens and forests. Some of these residents are villagers (people with developmental disabilities) and some are volunteers (co-workers and their children). Collectively, the village and its inhabitants are the living realization of Austrian pediatrician Dr. Karl Konig’s vision and Austrian scientist and educator Rudolf Steiner’s philosophy.

Steiner’s ideas defy simple description, but when he founded the Anthroposophical Society in 1924, he dedicated it to people everywhere who wanted to “foster the life of the soul, both in the individual and in human society on the basis of a true knowledge of the spiritual world.” The Camphill Village Movement (there are ten communities in the US and a hundred worldwide) is based upon providing a fully integrated environment, where people of all ages and abilities share home, work and social activities.

“Social therapy,” the continual creation of a healing social and physical environment, also plays a part. Like the Japanese Nobel laureate in literature Kenzaburo Oe, who wrote about what he learned from his mentally disabled son, adherents of this therapy point out that people with special needs are themselves teachers and care givers.

“What does it mean,” Camphill Village asks in its literature, “to recognize the spiritual integrity and unique destiny of each individual?” As Elias walks down the road with purpose on a summer afternoon, an answer comes to mind.

Garden Roof, City Hall, Chicago, May 2005.

Hundreds of deaths occurred in Chicago in the 1990s because of heat waves. In response, the city of Chicago, in conjunction with the United States Environmental Protection Agency, initiated the City Hall Rooftop Garden Pilot Project, part of the Urban Heat Island Initiative.

Green roofs help minimize urban heat effect, which occurs in metropolitan areas when the sun bakes pavement and roof surfaces, raising temperatures much higher than that of land surfaces in the countryside. A conventional rooftop can reach 140 degrees in summer, but when covered with a layer of soil and planted, it will tend to stay around 80 degrees thus reducing the surrounding air temperature and the need for air conditioning within the building.

Numerous other benefits come from planted rooftops. They absorb up to 50 percent of the rain that falls on them, reducing the surge of water that can overload urban sewer systems during heavy downpours. They protect the underlying roof’s waterproofing layer from sun exposure, helping it to last forty or fifty years instead of the standard twenty.

Over one hundred building projects are now underway in the city, incorporating one million square feet of green roof. They are part of Mayor Richard M. Daley’s plan to transform Chicago into one of the greenest cities in the world.

City Farm, Clybourn and Cleveland Avenues, Chicago, May 2005.

City Farm is a series of temporary sustainable organic farms built on vacant land leased from the city of Chicago. This site is adjacent to Cabrini Green, a housing project whose name has become synonymous with all that is wrong with public housing.

Founded and managed by Ken Dunn, a native Kansan with a family background in farming and a master’s degree in philosophy from the University of Chicago, City Farm begins by leasing vacant lots, cleaning them and then putting down a protective clay barrier to prevent leaching of any toxic materials contained in the site. Fresh soil is then brought in and fertilized with discarded trimmings from restaurants and grass clippings that would normally go to landfill. Unemployed and homeless people are invited to apply for apprenticeships and jobs on these sites as the land is planted with heirloom tomatoes, beets, carrots, potatoes, gourmet lettuces, herbs and melons. When the crop comes in, produce is sold to some of the city’s most stylish restaurants: Frontera Grill, Scoozi, Mod and the Ritz-Carlton. Chefs rave about the quality of the handpicked, heirloom tomatoes, often harvested just hours before their use.

Proceeds from these sales are used, in part, to allow for the additional sale of City Farm produce to neighborhood residents at much lower prices. In deciding what crops to plant, neighborhood tastes are taken into account.

When the land is sold, City Farm rolls up the compost, soil and fencing, and relocates. The city of Chicago currently has about eighty thousand vacant lots.

Dome Village, Los Angeles, California, August 1994.

This community of experimental fiberglass domes offers transitional housing for as many as thirty-four homeless people. Eight of the domes contain common facilities, including kitchens, bathrooms, laundries and computer rooms. The other twelve domes provide shelter for single individuals or families.

Activist Ted Hayes founded the village in 1993 as alternative for the many homeless people who are afraid of shelters. The domes allow greater privacy for the people who stay in them, and the village itself acts as a microcosm of society, providing residents with a setting in which they may stabilize their lives and garner the skills necessary to reenter the “real world.”

With their distinctive design, the domes are meant to call the attention of passing motorists on the nearby Harbor Freeway to the problem of homelessness. Initial funding for Dome Village was provided by the Atlantic Richfield Oil Company.

Ted Hayes has a long history of promoting innovative ways to help the homeless that incorporate problem-solving and individual responsibility. He is sometimes referred to as the “Rasta Republican”. In the 1980s he started a cricket team made up of Latino teenagers and homeless men, “Homies and Popz”. The team has played at Windsor Castle and is the subject of a forty-minute operetta commissioned by the Los Angeles Opera.

Ruins of Drop City, Trinidad, Colorado, August 1995.

Three of the original founders of Drop City met as students in Lawrence, Kansas, in 1961. As Timothy Miller reports in The 60s Communes, they referred to their practice of painting rocks and dropping them from a loft window onto the busy street below as Drop Art.

By 1965 the founders’ desire to live rent free and create art without the distraction of employment led them to a six-acre goat pasture outside Trinidad, Colorado, which they purchased for $450. Naming their community after their gravity-driven art was the easy part, building it a little harder. But having recently attended a lecture by Buckminster Fuller and now joined by a would-be dome builder from Albuquerque, they began with scrap materials and visionary optimism. Sheet metal was stripped off car roofs (for which they paid a nickel or a dime) and attached to the grid of a dome. These building materials not only provided shelter, but they also emblemized the group’s refusal to participate in consumerist society. Money, clothing and cars were shared, and they lived as quasi-dumpster divers.

Initially the community flourished. With a core group of twelve, it functioned as the founders had intended, a hotbed of art making. But a steady flow of publicity in underground and mainstream media, encouraged by resident Peter Rabbit, led to a torrent of guests. It has been reported that Bob Dylan, Timothy Leary and Jim Morrison visited but the historian’s chestnut, the primary account, may be less than reliable when it comes to the 1960s. By the time the community decided to abandon its open-door policy, it was too late: the founding members had left, and conditions had taken hold that would bring about a final dissolution in 1973. In 1978 the site was sold; proceeds helped rent space in New York City for exhibitions of the group’s work and publish it in Crisscros a magazine.

The domes sat on the land of A. Blasi and Sons Trucking Company until recently when they succumbed to gravity.

An Earthship at Earthaven Ecovillage, Black Mountain, North Carolina, April 2005.

Earthships, invented by American architect M. K. Reynolds, derive their name from his idea of them as “independent vessels to sail on the seas of tomorrow.” They are generally made from tires filled with rammed earth, though sometimes of bottles and cans. They are often configured to maximize the surface area on which solar panels can be placed and typically have rain catchments and a filtration system for water (the circular object seen at the corner of the building is a cistern). Not visible in this photograph is an all-glass south facing wall. In the winter when the sun is low in the sky, sunlight pours through it directly into the home. The warmth that results is retained by the high insulating coefficient of the three earthen walls enabling the house to be sixty-eight degrees with minimal heating. In the summer when the sun is overhead, the cool earthen walls maintain sixty-eight with little or no additional cooling. This home is sited so that on December twenty first the sun is just over the horizon of the ridge to the east.

The house is one of numerous innovative structures that comprise Earthaven Ecovillage. Because Earthaven’s 320 acres are mostly mountainous forest, all dwellings are built on slopes, leaving flat ground open for agricultural fields. Though still under construction, Earthaven has been completely off the grid since its inception in 1994. The central village is powered by a micro-hydro system and the water supply comes from a natural spring and is stored in a ten thousand-gallon water tank. Homes in the community are built of natural or recycled materials, and the entire site has been planned as a model of permaculture design.

Members pay annual dues, share title to the land and participate in a consensus decision-making process. Each community member is responsible for earning his or her own living. The village-scale economy includes numerous ecologically sound businesses such as Red Moon Herbs and the publication of Permaculture Activist and Communities magazines.

The community doesn’t have a single village-wide spiritual practice. “What many of us have in common is a reverence for the Earth and our land, and the belief that our land is alive and conscious and it’s our sacred duty to honor and care for it.”

Rabbi Chaim Adelman at Eretz HaChaim, Sunderland, Massachusetts, October 2004.

Eretz HaChaim (Hebrew for “the living land”) is a kosher, organic communal farm, founded in 2002 by ultra-orthodox Jews under the leadership of Rabbi Chaim Adelman. The commune, still in formation as of this writing, owns seventy acres of land.

Following an early Jewish rule that presages modern sustainable farming practice, every seventh year they will let their land lie fallow. In accordance with the Torah, the “corners” of their fields will be left to the poor—if no poor show up to glean, the produce from the corners will be donated to charity. As orthodox Jews they cannot milk cows on Saturdays, so gentiles will perform the task on that day. Their kosher organic chickens will not be fed grain during Passover. The community plans to be self-sufficient, with a synagogue, schools, a ritual bath and a swimming pool (the Talmud, a body of Torah interpretation, says that children must be taught to swim).

Eretz HaChaim represents a larger return to a Jewish farming tradition. Sweet Whisper Farm in Readsboro, Vermont, specializes in organic education and maple syrup harvested using horse-drawn wagons. Mitzva Farms in Waukon, Iowa, produces Yetta’s Chedda, A Bis’l Swiss’l and Mazel Rella.

Crenshaw High School, South Central Los Angeles, March 1994.

In the aftermath of the Los Angeles riots of April 1992, students at Crenshaw High School, with assistance from science teacher Tammy Bird and volunteer business consultant Melinda McMullen, created a garden out of a weed-infested lot behind the school.

Their first crop, harvested at the end of 1992, was donated to homeless people, but the next summer the group decided to help graduates of their program attend college. After selling $150 worth of herbs and vegetables in less than half an hour at a farmer’s market in Santa Monica, they found themselves well on their way.

Student managers run every aspect of the business. Each student “banks” his or her work hours and receives payment in the form of a direct scholarship paid to their college or university. The program also provides academic tutoring, SAT and college entrance exam preparation, mentoring and life skills training.

Over the years, Food From the Hood has been able to award $140,000 in college scholarships to its student managers.

Their “Straight Out the Garden” salad dressings are available in twenty-three states and more than two thousand stores, including Grand Union and A&P. They are also available on Amazon.com.

Scott and Helen Nearing at Forest Farm, Harborside, Maine, October 1982.

In the early years of the twentieth century, Scott Nearing’s pacifist beliefs and antiwar activism caused him to lose two college teaching jobs. As a young professor of economics at the University of Pennsylvania, he wrote essays such as The Great Madness and Oil and the Germs of War, asserting that the main purpose of the US military was “to guard the hundreds of millions of dollars…invested in ‘undeveloped countries.’” He was put on trial under the Espionage Act of 1918 and, though acquitted, publishers began to refuse his work.

Out of these experiences came an utterly new one. In 1932, at the height of the Great Depression, as he was approaching fifty, he married Helen Knothe. Together they bought a run-down farm in Vermont for three hundred dollars, built their own home and eleven other structures out of stone, and eventually grew 80 percent of the food they ate. Without using any animal labor, they gathered maple syrup and sold it as a cash crop (they refused to gather honey because they believed it exploited the bees’ work). Only one-third of each day was spent in what they referred to as “bread labor.” The rest of their time was divided between community service, professional activities and recreation, particularly music making. Nor were they lonely, the Nearings’ door was continuously open to visitors who wished to learn from and participate in their simple life. To enter one had only to be willing to work. And once again Scott published: Living the Good Life: How to Live Sanely and Simply in a Troubled World appeared in 1954, co-authored with Helen, and was followed by numerous other reflections on their homesteading life and beliefs. Living the Good Life proved consequential, becoming an Ur-text for the back-to-the-land movement of the 1960s.

In 1952, when Vermont grew too crowded for them, the Nearings moved to Maine and started the good life process all over again. It lasted until 1983 when Scott, aged one hundred, fasted to his death. Physically and mentally strong, the choice to end his life was a conscious one. On the day this picture was made, less than a year before his death, he had been out back chopping wood, and his handshake was powerful.

Defending himself at his espionage trial in 1919, Scott Nearing wrote: “The Constitution does not guarantee us only the right to be correct, we have a right to be honest and in error. And the views I have expressed in the pamphlet [The Great Madness] I expressed honestly. I believe they are right. The future will show whether or not I was correct.”

Fruitlands, Harvard, Massachusetts, October 2004.

Utopian experiments have failed for a variety of reasons, conflicts with the external world and internal dissension about leadership among them. Fruitlands, however, failed out of sheer impracticality predicated upon inordinate idealism.

After a radical school for children that he initiated failed, Bronson Alcott began Fruitlands in 1843 in a particularly beautiful landscape near Harvard, Massachusetts. Absolutely no animal products were consumed on the commune, hence the name Fruitlands. In fact, Ann Page, the only female member besides Alcott’s wife, was expelled from the community for eating a piece of fish. A total of eleven adults eventually joined, including Samuel Bower, who became a nudist upon realizing that clothing was spiritually stifling; and a man who reportedly ate nothing but apples one year and crackers the next. Also part of the commune was Samuel Palmer, who wore a long, flowing beard that was out of style, and upon whose gravestone appears the epitaph, “Persecuted for Wearing The Beard.”

Alcott seems to have been a remarkable man who made a lasting impression upon all those he met, including Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. An intellectual, educator and deeply religious figure, he was referred to as the “father of transcendentalism,” an idealistic belief system in which the world and everything in it is thought to have a spiritual basis.

Not only was the community vegetarian, no animal products were used whatsoever. Neither wool nor honey nor wax—not even animal fertilizer was used. Vegetables with roots that grew downward were forbidden because they disturbed worms. For a short time, Fruitlands thrived, but during a visit Emerson commented with prescience: “They look well in July. We shall see them in December.” And in fact, by January 1844, seven months after its founding, Fruitlands had fallen apart.

A much more pragmatic transcendentalist utopia was begun in Roxbury, Massachusetts, in 1841, when George Ripley and fifteen others founded Brook Farm. Although the community was composed of poets and musicians, it was predicated upon a belief in physical labor as a condition of mental well-being. And unlike the members of Fruitlands, they did sell their milk and vegetables and honey.

The Brook Farmers worked hard, and when the workday was over there was an extraordinary calendar of musical events, dramatic readings, plays, literary society meetings and parties, dances and picnics. It all ended in 1846 when a fire destroyed the community’s central building—little physical trace remains today of Brook Farm.

Recreated Bark Longhouse, Ganondogan State Historic Site, New York, July 2000.

Before Columbus disembarked on the shores of what would become America, there was no “wilderness”—the land was home to a hundred million people, most of them living in highly organized societies.

The Iroquois Confederacy was and is a political union of six North American Indian Nations. The people of the Six Nations refer to themselves as “people of the longhouse,” taking their identity from the traditional building that served as a communal dwelling and ceremonial hall, and which characterized the permanent villages in which the Iroquois lived.

This confederacy, perhaps the oldest democracy on earth, existed long before the Europeans arrived and took notice of it. It was based on two legislative bodies or “brotherhoods,” the elder comprised of Mohawks and Seneca, the younger of Oneidas, Cayugas and Tuscaroras. If these two “houses” were unable to agree on a matter the Onondagas would cast the deciding vote. The Iroquois equivalent of the Supreme Court was the Women’s Council, which settled disputes and adjudicated legal matters. Implicit in Iroquois political philosophy is a commitment to the highest principles of human liberty, including freedom of speech and the right of women to participate in government.

Underlying all deliberations was a spiritual figure, the Peacemaker, who gave the Tree of Peace as a symbol of the Great Law of Peace. Beneath the tree, the Nations buried their hatchets, and atop it sat the Eagle-who-sees-far.

Iroquois law had a strong influence on Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and other framers of the US Constitution. The theory that the Constitution is based on the Iroquois Great Law of Peace rather Greek democracy is gaining credence. Certainly Jefferson adopted Iroquois symbols: the Tree of Peace became the Tree of Liberty, and the Eagle-who-sees-far became the symbol of the new American government (clutching 13 arrows).

Sister Miriam in front of her Straw Bale Home, Genesis Farm, Blairstown, New Jersey, May 2005.

When 140 acres of farmland were donated to the Dominican Sisters of Caldwell, New Jersey, in 1980, the nuns realized they had an opportunity to do something about their growing concern that the Earth was being endangered by environmental degradation.

Under the persuasive leadership of Sister Miriam MacGillis, they built a teaching center and started a community supported farm. A large solar array was installed and straw bale buildings were constructed, including Sister Miriam’s house.

At the heart of Genesis Farm is a commitment to the teachings of Catholic eco-theologian Thomas Berry. His doctrine, Earth Literacy, is based on the belief that the divine is revealed in the vast biological and cultural diversity of this planet.

Berry was one of the first to propose the idea that the Earth’s environmental crisis stems from a spiritual one. He maintains that we suffer from a kind of spiritual autism, that we no longer feel our kinship with other life on this planet. The challenge now is to satisfy our essential human needs without destroying the biodiversity that makes our world so nourishing and rich. Central to the doctrine of Earth Literacy is the conviction that any viable future for the human species is dependent upon the viability of the Earth.

Dacha/Staff Building, Gesundheit! Institute, Hillsboro, West Virginia, April 2004.

When Dr. Patch Adams envisions the forty-bed rural community health care facility that he refers to as “the free silly hospital,” he hopes it will be “funny looking, full of surprises and magic.”

Adams’ desire to humanize healthcare has always taken radical form. From 1971 to 1983, he and nineteen other adults and their children moved into a six-bedroom home and called themselves a hospital. Three of the adults were physicians. They were continuously open to patients and saw fifteen thousand people over a period of twelve years. Initial doctor/patient interviews were three to four hours long, “so that we could fall in love with each other.” Since no donations were received nor was there any outside funding, the staff eventually left and the hospital closed.

This led Adams to his present period of fundraising, which he often does in the guise of a clown. A three hundred-acre farm has been purchased in West Virginia—chosen because it is the most medically underserved state in the nation—and two buildings have been constructed. The Dacha/Staff Building was designed by the Yestermorrow Design/Build School of Warren, Vermont.

Amongst numerous other unconventional practices, the hospital will not charge for its services nor will it carry malpractice insurance. Healing arts such as acupuncture, massage, yoga, herbalism and faith healing will be integrated into patient care. Patients and staff will stay at the hospital, and forty beds will be available for “plumbers, string quartets, and anyone wanting a service-oriented vacation,” reflecting Adams’ vision that the health of the individual cannot be separated from the health of the community. Although the free silly hospital is not yet built, the idea of it can, and does, influence the dialogue on health care delivery systems.

Halcyon Temple of the People (Blue Star Memorial Temple), Halcyon, California, January 1997.

In 1873, Mademoiselle Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, a young Russian noblewoman and journalist who had recently arrived in New York from Paris, met Colonel Henry Steel Olcott at a séance. Two years later, they and others formed the Theosophical Society, dedicated to the exploration of spiritualism and the occult.

In 1877, Blavatsky published Isis Unveiled, which contained the doctrines, teachings and practices of Theosophy, supposedly derived from a group of masters known as the Mahatmas of Tibet. Though Blavatsky claimed that the masters asked her to act as their conduit to western people, Theosophy has always been plagued by charges that its teachings were plagiarized from a hodgepodge of religious, philosophic and scientific sources.

Despite such charges Theosophy has thrived, with approximately thirty-thousand current members, of whom four-thousand three-hundred reside in the US. An element of its appeal is the notion that all religions are attempts by man to ascertain “the Divine,” and as such each religion has a portion of the truth. Throughout its history, Theosophy has claimed many well-known artists as adherents, both in America and abroad, including Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Franz Kafka, T. S. Eliot, Arthur Dove, Wallace Stevens and W.B. Yeats.

The Theosophists of Halcyon arrived in California in 1903 from Syracuse, New York. After acquiring a hundred acres, they organized the Temple Home Association according to socialist principles, with all property held in common. The Halcyon Temple was built in 1923-1924. Its triangular shape is meant to symbolize the heart as well as the trinities that are central to many of the great religious teachings throughout history. The seven doors are symbolic of the “key number” of the universe (seven days in a week, seven notes between octaves, seven colors of light). All inside dimensions and angles are multiples of seven. The temple still functions as the center of the community. Though no longer a cooperative, half of the people currently living in the town are practicing Theosophists.

Heathcote Community, Freeland, Maryland, May 2005.

When Ralph Borsodi founded the School of Living in the 1930s, the terms “permaculture” or “sustainability” did not exist. Borsodi was simply a philosophical man whose life led him to believe that a return to the land was the cure for all that ailed civilization.

His background might have predisposed him to think this way: his father had written the introduction to Bolton Hall’s A Little Land and a Living, a book which led to the founding of Little Lander colonies in California. But the real impetus occurred in the early 1920s when the house in which he and his wife were living was sold and they found themselves without a home. They moved to the country and began homesteading. As he acquired the skills necessary to live in the country with self-reliance, Borsodi began to work on his ideas producing treatises such as This Ugly Civilization and Flight from the City. His writings influenced many including Helen and Scott Nearing who moved to the country a few years later and whose own writings also encourage self-reliant, agricultural life.

The School of Living was founded to teach the pragmatics of small-scale subsistence farming and living, such as carpentry, organic gardening and food storage. Self-sufficiency was at the core of his belief system, but he also considered the broader aspects of modern society and was particularly concerned about the overuse of nonrenewable resources—a topic of great importance today.

After World War II, Borsodi’s mission was taken up by Mildred Loomis. In 1965, under her leadership, the School of Living purchased a 150-year-old gristmill in Maryland to serve as the center of a community where the pursuit of personal and spiritual growth could be interwoven with a lifestyle respectful of the land.

Heathcote, as it was named, has thrived, and in accordance with its communal belief that we live on a planet in crisis, it practices and teaches permaculture. A contraction of the words “permanent agriculture” and “permanent culture,” permaculture is a philosophy that informs an approach to planning, building and maintaining sustainable systems, the ultimate expression of which is a sustainable community. Nature itself is the model for permaculture; close observation and working in concert with the natural world are at the heart of this thinking.

The long foreground of Heathcote—from Borsodi’s personal transformation to Mildred Loomis’s assumption of leadership,nfrom Heathcote’s formation as a 1960s commune to its present role as a center of permaculture—offers a model of communal evolution.

Roosevelt Public School, Roosevelt, New Jersey, June 2005.

A wave of Jewish emigration from crowded tenements in crowded cities to the countryside occurred in the 1930s, when the vicissitudes of the Great Depression led to the creation of rural cooperatives across the country—including the Jersey Homesteads, about sixty miles from New York City. The members of the community also built a cooperative garment factory; Benjamin Brown, the “father” of the Jersey Homesteads, hoped that a better life for community members could be structured around work on a self-sustaining farm in the growing season, combined with winter employment in the garment factory.

This mural, created by the soon-to-be-renowned artist Ben Shahn, traces the story of the Jersey Homesteads in three panels, from the arrival of immigrants at Ellis Island, to the planning of the cooperative community, to the movement from the city to the simple but light-filled homes in the countryside. Early supporters of the community, including Albert Einstein and painter Raphael Soyer, are also depicted. After completing the mural in 1938, Shahn and his wife Bernada decided to become residents themselves.

For a while it worked. Two hundred homes were built, exciting ideas clashed at town meetings, and other artists followed Soyer and Shahn, until the small town had a remarkable number of painters, poets, weavers and potters. But the agricultural cooperative failed as it was discovered that there were no true farmers among the urban pioneers. And the factory became a button-making facility—the garment trade is always a risky business, but particularly so at the height of the Depression.

Jersey Homesteads was renamed Roosevelt shortly after World War II. Bit by bit the elements of communalism disappeared, except for the ongoing Roosevelt Arts Project (RAP), begun in 1986 by Bernada Shahn and the artist Jacob Landau, among others. RAP is dedicated to bringing together artists in a variety of media, to foster collaboration and present often-experimental work to the public. Thus at Roosevelt, of which it was said, “if there were two people in the room, there were three opinions,” a measure of true community has finally been achieved—just not in the fields or the town hall.

Robin Hood Estates, Smythe Avenue, San Ysidro, California, March 2005.

All that remains of the Little Landers experiment in single-acre sustainability is William Smythe’s name on a street sign in San Ysidro, California, less than a mile from the Mexican border.

Nearly a century ago in 1909, Smythe led the movement to purchase 550 acres, which would be set up with proper agricultural irrigation and subsequently sold as small plots to people who would live on them and cultivate them intensively. Eventually three “Little Lander” colonies were established in southern California, taking their movement’s name and inspiration from A Little Land and a Living by Bolton Hall. Within a few years, the San Ysidro colony boasted two hundred homes and five hundred settlers; contemporary newspaper articles praised the prosperous and healthy life to be found there.

In 1915, however, a severe drought led the city of San Diego to hire men who practiced the new science of pluviculture, or rainmaking. Charles and Paul Hatfield set up great evaporating tanks and twenty-four-foot-high towers; nearby farmers heard explosions and saw flames as billows of smoke filled the sky. Within four days great rains fell across southernnCalifornia. After three weeks of storms a dam broke, causing massive flooding and the loss of twenty lives. The Hatfields fled San Diego when they learned a lynch mob was coming after them.

The San Ysidro Little Lander Colony never truly recovered from the effects of the flood, and it eventually ceased to be a true community in 1922. Charles Hatfield was denied his rainmaking fee by the city of San Diego, which refused to pay him unless he assumed liability for the $3.5 million in damages caused by his doings. His life was the subject of the 1956 film The Rainmaker, starring Burt Lancaster.

Liz Christy Garden, Bowery and Houston Streets, New York City, June 2005.

In 1973, artist/activist Liz Christy and a group of like-minded New Yorkers calling themselves the Green Guerillas began taking over abandoned lots on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in order to convert them to gardens. Their first success came at a site on the corner of Houston and the Bowery, in a vacant lot where drug users found a haven, and two homeless men had frozen to death in a cardboard box a few months earlier.

Over a period of thirty years, eight-hundred fifty gardens were successfully fought for by the Green Guerillas, and others including the legendary eco-activist Adam Purple, so known for his all-purple attire worn while bicycling through Central Park, gathering horse droppings to be used as fertilizer. At least fifty-four of these gardens are now being transferred to the jurisdiction of the Parks Department, to become permanent additions to the city’s urban landscape.

New York City has a history of community gardening going back to the 1930s. During the Great Depression, five-thousand relief gardens were sponsored on vacant lots, for use by unemployed people. The program was cancelled in 1937 when the US Department of Agriculture initiated a food stamp program. For the next few years the public garden program lay dormant, but when World War II broke out the city announced that all available city-owned land could be cultivated as Victory Gardens. With the war’s end and the advent of frozen food the Victory Garden program came to a conclusion.

The continued existence of that first garden at Houston and Bowery is currently threatened by the construction of an adjacent upscale apartment complex. Many other community gardens have fallen victim to the forces of real estate development or have been involved in conflicts resulting from land speculation—Adam Purple’s world-renowned Garden of Eden was destroyed in 1991.

Liz Christy died of cancer in 1986, at the age of thirty-nine. The garden was immediately named after her.

Ruins of the General Assembly Hall and Hotel, Llano del Rio, Antelope Valley, California, November 1993.

After losing his 1911 bid to become mayor of Los Angeles, Job Harriman, a prominent lawyer and a socialist of great conviction, founded Llano del Rio to demonstrate that socialism could work.

The site of a former temperance colony sixty miles northeast of Los Angeles was purchased for a down payment of fifteen dollars, and on May Day 1914 five families, five pigs, a team of horses and a cow came to Llano. Three years later, there were nine hundred residents.

Conditions were harsh and demanding, yet the colony grew and prospered. Many members later recalled those years as the best, most exciting time of their lives. Freedom from capitalism, a varied social, intellectual and recreational life, and mass participation in the democratic process of the community gave Llano an edenic quality.

The problems that undid the colony were internal dissension and an inadequate water supply. A group of dissidents, who met secretly at night in the surrounding sagebrush, deeply disrupted community discussion and debate. The “brushers” might, in fact, have been saboteurs planted by Los Angeles Times publisher Harrison Gray Otis, who had opposed Harriman’s mayoral campaign and was known for his underhanded tactics.

When a conflict over water rights arose between the colony and neighboring citizens of the Big Rock Water District, Llano had to go to court over its right to irrigate. The opposing attorney referred to the group as “socialist plunderers,” and the case was lost. From that moment on, the failure of Llano was inevitable.

In 1918, a splinter group moved to a site in Louisiana, where they survived in a limited form for the next twenty years.

In the 1940s, Aldous Huxley lived for a year in a house that had belonged to the original Antelope Valley colony—he wanted to absorb any remaining utopian karma.

Lost Valley Education Center, Dexter, Oregon, April 2004.

Round structures occur in many cultures, from the hogans of the Navajo to the trulli of southern Italy to the krads still constructed in Africa today. Yurts were originally shelters for nomadic peoples living on the grass-covered high plateaus of Central Asia. Regardless of the culture, circularity is associated with the sacred—living in or worshipping in a circle is variously linked with the sun, the full moon, the cycles of the seasons, life. The fact that several yurts are part of the infrastructure of Lost Valley thus seems appropriate, given the cycles of conflict and transformation undergone by the community since its founding in 1989.

Today a rural community of about twenty adults, Lost Valley seeks to achieve a balance between a strong ecological focus and a commitment to its functional extended family. However, during the year of 1996, several painful transitions began at Lost Valley—many people left, and friction between old and new members was so high that one resident reported being fearful for his own safety. In the midst of this difficult time, Deborah Riverbend came to Lost Valley and gave a workshop in Naka-Ima, or “Here Now.” Ever since, this philosophy and the very phrase “Here-Now” have become an invocation of a way of being that transformed the community.

Lost Valley currently offers workshops in Naka-Ima, which it refers to as “The Heart of Now,” and collectively lives by this principle. Members support one another emotionally, sharing life’s joys and sorrows —and honestly admitting that sometimes it just doesn’t work.

Milagro Cohousing, Tucson, Arizona, March 2005.

Milagro means “miracle” in Spanish. Like the hundred or so other cohousing communities created in the United States in the past fifteen years, Milagro is composed of individual homeowners who are consciously committed to living in community and in accord with ecologically sound principles.

Of Milagro’s forty-three acres only eight are used for houses. (Part of the “miracle” is the variance from local zoning regulations that it received. Normally, a maximum of one home per three acres is permitted in this part of Tucson. Suburban or outlying communities frequently employ such provisions as a means of maintaining their rural character.) The remaining thirty-five undeveloped acres of Milagro have gone into a conservation easement, open to the public as a nature reserve and protected from development

Milagro’s commitment to being in balance with nature is particularly manifest in its water harvesting methods. Believing that this resource will become increasingly scarce, all water that exits the community’s homes, including “grey water” that has been used for cooking and bathing, is recycled through a wetlands system and eventually returned to be used to irrigate plantings. Every structure is built with a steep roof, allowing rainwater to be directed through gutters and funneled down water spouts into cisterns, in an active water-harvesting system. Earthen basins and berms and the extensive use of native plants slow down and hold rainwater, so that it doesn’t run off before plants have absorbed it.

The World Water Forum has predicted that sixty-six countries containing two-thirds of the world’s population will experience moderate to severe water scarcity by 2050. Whether the global water crisis is yet to come or is already present remains subject to debate, but evidence of global environmental problems continues to accumulate rapidly. In the year 2000, according to the International Red Cross, more of the world’s millions of refugees had fled their home places because of environmental reasons than because of war.

Bed and Breakfast, Wiscoy, New York, August 1996.

In 1808, Charles Fourier, a clerk living in Lyons, France, published Theory of the Four Movements. In it he criticized the immorality of the business world and the anarchy of free competition, arguing that, “truth and commerce are as incompatible as Jesus and Satan.”

Fourier advanced a new system of cooperation based on what he called “phalanxes,” meticulously planned model communities with exactly 1,620 people of all classes (twice the number of distinctive human personality types he had identified), whose lives would be structured for maximum collaboration and fulfillment.

Underlying Fourier’s theory was the notion of “passional attraction,” which he defined as “the drive given to us by nature.” In his view, complete sexual gratification would lead to perfect harmony. During Fourier’s lifetime a few communities were initiated in France—including one begun by the industrialist Godin, who set up his cast-iron kitchen goods factory in Gurse as a modified Fourierist Phalanx.

There is much in Fourier’s writing that is laughable nonsense: he believed that the ideal world he was helping to create would last eighty-thousand years during which six moons would circle the Earth, there would be thirty-seven million poets equal to Homer, thirty-seven million mathematicians equal to Newton and the seas would become oceans of lemonade. But there was also much that was perceptive in his writings and he was able to attract a widespread following.

After Fourier’s death in 1837, many of his followers came to the US and founded a succession of short-lived communities. Over two dozen phalanxes were established—thus making Fourierism the most popular secular community movement of the entire nineteenth century. None of the America phalanxes were full-scale either in numbers or in constructing a large “phalanstery” according to Fourier’s grandiose and imaginative plans. One of the most renowned of all American communal experiments, Brook Farm, in Roxbury, Massachusetts, became a Fourierist phalanx and flourished as such, until a disastrous fire brought about its end in 1846.

Among these phalanxes was the Mixville Association in Wiscoy, New York, founded in 1844. When this photograph was made, in 1996, it was functioning as a bed and breakfast.

Mormon Temple, Nauvoo, Illinois, May 2005.

Nauvoo was a swampy backwater on the Mississippi River in 1840 when Joseph Smith and his disciples, fleeing persecution in Missouri, descended upon it. In just four years, they transformed it into a thriving city of twenty thousand.

Mormonism, a distinctly American religion, was founded in 1830 when the twenty-four-year-old Smith published the Book of Mormon (translated from “reformed Egyptian” by the young Vermonter after the angel Moroni revealed its existence to him in a series of nighttime visits). The book contains an abridged history of a Jewish clan that arrived in America by boat and became the American Indians. Among its other revelations: the true location of the Garden of Eden is in Missouri, on a piece of land that’s now a parking lot—near Harry Truman’s home.

The years between 1841 and 1844, during which the Temple in Nauvoo was under construction, were particularly febrile ones for Smith. Influenced by Masonic ceremonies and the Jewish mystic tradition known as the Cabala, Smith expanded the rituals and practices of Mormonism. In particular he introduced “celestial” marriage, in which not only men but a few women secretly took “plural” spouses.

When rumors of this practice surfaced, scandalized residents of Nauvoo bought a printing press and published the first issue of an oppositional newspaper. In response, Smith, who maintained the second largest standing militia in America, declared martial law and ordered his followers to smash the printing press. When subsequently charged by the governor of Illinois with treason, Smith surrendered to the jail in nearby Carthage. There, he and his brother were shot to death by a mob, composed, in part, of members of the state militia assigned by the governor to protect him. The remaining Mormons were further persecuted and eventually forced to leave Nauvoo in the dead of winter.

The town was soon bought by French communist followers of Etienne Cabet. Fifteen hundred “Icarians,” so called because of their belief in Cabet’s novel, Travels in Icaria, an eight hundred-page amalgam of utopian thought, moved in. Writing in America’s Communal Utopias, Robert P. Sutton reports that they led a particularly rich cultural life for frontier America, with a library housing four thousand volumes. But financial difficulties and a series of strict edicts promulgated by Cabet— forbidding tobacco, hard liquor, complaints about the food, and hunting and fishing “for pleasure”—brought about dissension and the eventual dissolution of the community.

The town of Nauvoo is now a major Mormon tourist destination, attracting a million visitors a year. In 2004 the lieutenant governor of Illinois expressed official regret to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for the events that occurred in 1844

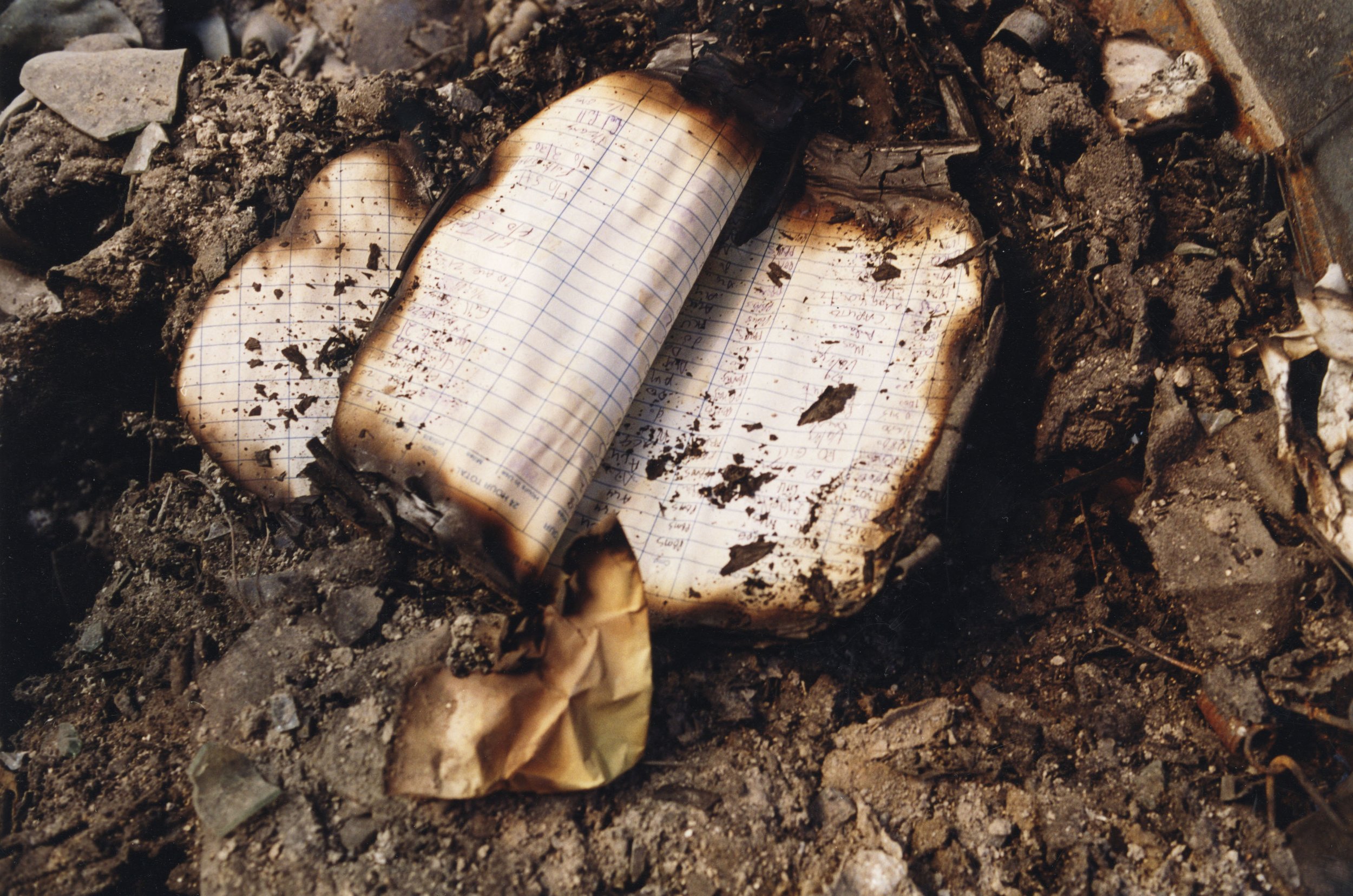

6200 Block of Osage Avenue, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, July 1993.

MOVE was founded in the early 1970s by Vincent Leaphart, who later changed his name to John Africa, and Donald Glassey a white college professor who shared Africa’s interest in philosophy and natural laws. They called their belief system “The American Christian Movement for Life” and this was eventually shortened to MOVE.

Africa’s teachings to the group of followers he developed were vehemently opposed to all forms of government including that of the United States. In an early self-description the group declared: “MOVE’s work is to stop industry from poisoning the air, the water, the soil, and to put an end to the enslavement of life—people, animals, any form of life.” After moving to a new home in west Philadelphia, MOVE felt impelled to broadcast profane anti-government messages from a loudspeaker and they harassed their neighbors in other ways. Practices consonant with their naturalist beliefs included: living without heat, running water, or electricity; eating only raw fruits and vegetables; refusing to bathe with soap; and allowing stray animals to enter the group’s home at will.

An August 1978 confrontation with police left one officer dead. Subsequently, nine members of the group were convicted of third-degree murder. Seven years later, on May 14, 1985, police arrived to serve arrest warrants on four MOVE members: a ninety minute gun battle ensued. Later that day Mayor Wilson Goode, the first African American mayor of Philadelphia, authorized police to drop a bomb from a helicopter onto a fortified bunker on the roof of the MOVE house. The bomb failed to pierce the bunker but it did start a fire which killed six adults and five children in the building. Because the Philadelphia Fire Department did not fight it, the ensuing general fire burned sixty-one homes on three city blocks. All residents had previously been evacuated from the area. The fire left 250 people homeless.

In a 1996 court decision the City of Philadelphia was ordered to pay $1.5 to certain survivors of the incident or relatives of the dead. The jury ordered both the Chief of Police at the time of the tragedy and the Fire Commissioner to pay $1 a week for eleven years to Ramona Africa, the only adult survivor. In a previous case the parents of the children who died were paid twenty five million dollars and it was noted that regular visits to a nearby park by the MOVE children should have made it possible to isolate them from the violence.

The city rebuilt all of the houses on Osage Avenue. The construction was shoddy—years of repairs could not remedy it. All of the rebuilt row houses have now been condemned with various legal and financial consequences.

N Street Cohousing, Davis, California, March 2005.

N Street Cohousing began in 1986 when two neighbors tore down the fence separating the yards of their 1950s tract houses. Over the next few years, more and more fence-removing parties were held on N-street as the backyards of seventeen homes were gradually joined together to make a beautiful open space with vegetable and flower gardens, a play structure, a hot tub, a sauna, a chicken coop and a pond.

Eventually, the neighbors began eating together. Feeling more fulfilled in their lives as a result of their common backyard and community meals, the group decided in 1991 to become a true cohousing group, and the large garage of one home was designated as a community center and equipped with a communal kitchen and dining room that could also function as a meeting room. Other initiatives have included a community laundry room, a wood working shop and a tool room.

At present, a brand new community house is being built, completing the cohousing cycle, albeit retroactively.

Although it arose through a process of gradual evolution within the midst of a suburban neighborhood, N Street has all the attributes of a classic cohousing community. The thirty-eight adults and seventeen children of the community share many of life’s joys and pains—and some of its meals—with one another, while maintaining separate homes and incomes, and privacy when needed. N Street has become a model for other groups in suburban America who are turning alienating housing into real community by tearing down the fences.

New Buffalo Bed and Breakfast, Arroyo Hondo, New Mexico, August 1995.

Hundreds of communes were established in America in the late 1960s, but nowhere were they as concentrated as in the northern New Mexico town of Taos. Within a few years, at least twenty-five communities were founded, including the Hog Farm (which provided security at the Woodstock Festival), Morningstar East (established by a group fleeing violence against them in California), the Lama Foundation (a spiritual retreat that still survives despite a 1996 wildfire, which destroyed nearly all its buildings except the central dome), and the Family (a group marriage of fifty adults, most of whom lived in one house with one upstairs bathroom—and many toothbrushes around the sink).

The exemplar of the Taos communal scene was New Buffalo, founded in 1967 by a group of people fascinated with Native American culture, on land donated by a wealthy young man intent on giving away his inheritance. The name “New Buffalo” was chosen because the founders wanted the commune to function as the buffalo had for Native Americans—provider of everything.

New Buffalo was an agrarian commune, simultaneously struggling with living off the land and coping with the instability of large numbers of short- and long-term visitors passing through Timothy. Miller points out in The 60s Communes that this conflict between openness and providing for newcomers may have been the central paradox of 1960s communalism: the more successful a commune became, the more attractive it grew to outsiders. The difficult decision to screen outsiders, and the means of initiating them into the daily practices and ethos of the group, often determined the fate of a commune. New Buffalo managed to survive in some form for nearly two decades, despite what has been termed the “Hippie-Chicano War”: vandalism, and in some cases brutal violence, were directed at the Taos communes by members of the local population who resented much about the communards, including their ability to buy land or get up and leave if things got tough.

By the mid 1990s, the ownership of New Buffalo had reverted to Rick Klein, the young man who’d given the land away many years before. He transformed it into New Buffalo Bed and Breakfast. At last account, it was for sale.

New Elm Springs Colony, Ethan, South Dakota, July 2005.

In 1516, Thomas More published Utopia. A year later, Martin Luther nailed ninety-five theses to a church door in

Wittenberg. And in 1525 at a meeting in Zurich, the early Anabaptists repudiated infant baptism in favor of “true Christian” adult baptism. Among this most radical wing of the Protestant Reformation were the Hutterites, a sect which took its name from Jacob Hutter, an early leader. They believed strongly in pacifism, communal ownership of all goods and the separation of church and state.

For the next century, under the protection of Moravian nobles, the Hutterites grew prosperous and their numbers swelled to perhaps thirty thousand. But the sect, which throughout its history has been persecuted for its distinctive beliefs, was expelled from Moravia in 1622. After a century and a half of migration, they began to settle in Russia with a promise of exemption from military duty. When this privilege was withdrawn in 1871 they left, and a few years later settled in South Dakota

Despite the hardships of their early years on the prairie, the Hutterites’ numbers grew steadily until World War I. As pacifists, their young men resisted service but, with no conscientious objector laws in place, draft-eligible males were arrested. When two of them were tortured to death while in custody, the Hutterites hastily moved to Canada, under another promise of exemption from active duty.

During the dark days of the Great Depression, the state of South Dakota was in desperate need of tax revenue, and the highly successful Hutterites, whose colonies refused any form of state aid, were invited to reoccupy their former lands. Today, forty thousand Hutterites can be found throughout the western United States and Canada, where their remarkably successful communities adopt whatever modern technology they find useful and live according to beliefs first embraced in 1525.

Roofless Church, New Harmony, Indiana, May 2000.

In the early 1800s, Robert Owen, a wealthy industrialist, took on the role of social theorist after radically improving labor conditions at a Scottish mill while increasing profits. New Lanark was famous throughout Europe because the minimum working age had been raised to ten, a form of health insurance was initiated, and working hours were shorter than at other mills. Owen came to believe that by changing the conditions of people’s lives it was possible to change their character, and that the final aim of character formation should be happiness. Happiness, he held, “will be the only religion of man.” He and other similar thinkers of the time were referred to as socialists because they had a theory of society.

The opportunity for Owen to put his theories into practice came in 1824, when he purchased the entire town of Harmony, Indiana, and turned it into America’s first secular utopian experiment. But what had worked in a narrow and isolated mill valley in Scotland did not work in the United States. Despite the participation of prominent scientists and of Owen’s four highly educated sons, the experiment failed. There were many reasons: the purchase of a ready-made town did not allow members to gain the shared satisfaction and unity of purpose that might have come by building from scratch; deep disagreements churned between Owen and American co-founder William Maclure over education (leading some to dub the town “New Discord”); and the frontier farmers and mechanics who responded to Owen’s invitation to join a new “community of equals” took him at his word and resented the “uppity” standards of speech, table manners and courtly rituals imposed upon them by the leaders. Despite the brevity of its life as a formal experiment, New Harmony proved highly influential throughout the nineteenth century. Without a community against which they might be measured, Owen’s ideas could stand for general reformist principles and they did.

The Roofless Chapel was commissioned by Jane Blaffer Owen, widow of a descendent of Robert Owen, and designed by architect Philip Johnson in 1960 to echo the mark left by New Harmony as a place of inspiration. Johnson’s concept was that only one roof—the sky—can encompass all worshipping humanity. The dome was built in the form of an inverted rosebud tying it to the New Harmony Community of Equals, whose symbol was the rose.

Homecoming Day, Nicodemus, Kansas, July 2005.

During the Reconstruction period following the Civil War, tens of thousands of former slaves fled the South in search of true freedom and a chance at an improved life, one in which they would be able to work for fair wages and own land.

“Bleeding Kansas” had paid a terrible price (the loss of fifty-five lives to violence between pro- and antislavery forces) before it was able to enter the Union as a free state. When fliers began to appear in the South encouraging blacks to take the railroad to a new promised land—a state that had fought for and defined its beliefs—they responded in great numbers. Referred to as “exodusters,” the men and women of the Black Exodus built shanty towns on the outskirts of Kansas City and Topeka, and founded new towns like Nicodemus, named for a legendary figure who came to America on a slave ship and later purchased his freedom.

The desperate families who settled in Nicodemus in September 1877 had to walk fifty-five miles from the railroad depot in Stockton to their new home on the windswept prairie. When Willina Hickman, a young exoduster who kept a diary of her experiences, arrived in the spring of 1878, she was shocked to see families living in dugouts in the ground. Just nine years later, however, the booming town of five hundred had at least five churches, a bank, four general stores, a literary society and an ice cream parlor. To attract the Union Pacific Railroad to the community, Nicodemus approved the issuance of $16,000 in bonds, but the railroad bypassed the town, and a long decline set in.

All the black towns of Kansas have disappeared, except for Nicodemus. It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1976. Every year on the last weekend in July, residents and former residents of Nicodemus celebrate their pasts, both recent and ancestral.

The story of Nicodemus is symbolic of the pioneering spirit of African Americans, who participated in every aspect of the shaping of the American West. They trapped, led expeditions and rode for the Pony Express. They also served in the military as “buffalo soldiers,” a name given them by Native Americans in admiration of their strength, persistence and durability.

Old Economy, Ambrose, Pennsylvania, August 1995.

George Rapp and his followers came to America in order to practice their religion free of governmental persecution. They left Germany and made their way to Southern Indiana, arriving in 1814.

Although their group was initially ravaged by malaria, they persevered and built a substantial town called Harmony. Relations with other communities were warm; the Harmonists gave financial assistance to other religious groups, and when they needed to make purchases, they did so from their co-communalists. But relations with distrustful neighbors proved highly problematic and, at times, violent. Particularly at issue was the Pentecostal Rappites’ commitment to celibacy. As Karl J. Arndt reports in America’s Communal Utopias “One Indianan wrote to the state general assembly, urging the outlawing of celibacy: ‘as there is many young Girls of Ex[c]elent Conduct and Beheavor in [H]armony And many young men of Good parts...it is shurly not Right that those who are man and wife should not Enjoy [each]other as such [just to] please the old gentleman.’”

In 1825 ongoing disputes with neighbors led the Rappites to sell Harmony to the socialist Robert Owen and to start over again in Pennsylvania, where they built a new home, Economy. Once again they thrived, creating a community that in many respects, especially in its cultural and musical activities, resembled a European court. But the issues surrounding celibacy continued to trouble them, and this time the problems began to develop among the Rappites themselves. Some people, but not all, were allowed to elope and rejoin the community, and between 1826 and 1829, Rapp himself caused a major uproar because of his personal involvement with an unusually beautiful young woman, Hildegard Mutschler. He enraged many when he made her his personal assistant in alchemy experiments to find the legendary “Philosopher's Stone,” said to turn base metals into gold.

Despite increasing wealth, continued insistence on celibacy diminished the Rappites' numbers. In 1916 the society was disbanded and what remained of its property went to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Old Economy became a state historic site, rented out, on occasion, for wedding receptions.

The formal garden pictured was meant to evoke the Garden of Eden. Among its many symbolic representations is the statue of Harmony, depicted as “a woman clothed with the sun.”

Oneida Community Mansion House, Oneida, New York, August 1996.

The members of John Humphrey Noyes’ highly religious and communistic Oneida Society believed that people could become perfect simply by accepting Christ into their souls. This was reasonable enough, but everything that followed that simple belief was radical to the point of heresy. God was both male and female, and thus the community was governed by men and women alike. In the spirit of the holy community of Christians, every member of the community should equally love everyone else, including sexually. Monogamous marriage was a tyranny, “egotism for two,” and was replaced by the enlarged family that came to be known as “complex marriage.”

Eventually a hierarchy developed in which the most spiritual members had the most access to sexual contact (Noyes presumably at the top of the ladder). Unwanted pregnancies were avoided by “male continence,” whereby “the skillful boatman may choose whether he will remain in the still water…or run his boat over the falls.” To hold together the web of emotionality that was associated with complex marriage, members engaged in “mutual criticism,” in which the person being discussed remained silent while every aspect of his or her being was open to analysis.

Quite remarkably, it worked. The community, which held all property in common, thrived at Oneida from 1848 until 1881. In 1867, a eugenics experiment called stirpiculture was introduced—a committee decided who would procreate with whom. Polly Held, seen here in the garden of Oneida in 1996, is the great-granddaughter of a stirpiculture union between John Humphrey Noyes and a female member of the community.

In August of 1879, reacting to internal pressures from dissatisfied lower spiritual-status members, as well as members anxious to have “special love” and committee-free procreation, the society discontinued “complex marriage” and transferred the community property to a joint-stock company in which everyone held shares. Former members could continue to live in the mansion (their descendents still do) and work in various Oneida industries. Their highly successful animal trap company was transformed into Oneida Limited, the well-known maker of silverware.

In a sense, the community, while dissolving, wrote its own eulogy: “The truth is, as the world will one day see and acknowledge, that [we] have not been pleasure-seeking spiritualists, but social architects, with high religious and moral aims, whose experiments and discourses [we] have sincerely believed would prove of value to mankind.”

Piedmont Biofuels, Pittsboro, North Carolina, April 2005.

The original diesel engine invented by Rudolf Diesel in Germany in 1893 ran on peanut oil. Henry Ford, who powered his first cars with ethanol, a plant-derived energy source, shared this belief in biomass fuels and their virtues, but around 1920 the oil industry all but halted their use in America.

Leif Forer, Rachel Burton and Lyle Estill founded Piedmont Biofuel Co-op in the fall of 2002. Worker-members produce pure biodiesel (B100) from waste vegetable oil collected from local restaurants. After it has been refined, the vegetable oil can be used in any standard diesel vehicle. The fifty co-op members can fill up their cars from this tank or have it delivered. Although the co-op has been a promoter of “micro-nodal” energy production, offering classes and conferences and helping other small co-ops start up (“We have long suggested that homemade biodiesel holds the promise of upending the overarching, top-down energy infrastructure that holds most of us in its grasp”), when an abandoned chemical factory near the co-op recently became available, the decision was made to expand. The co-op now has the capacity to produce up to one million gallons of biodiesel per year.