The Itinerant Vision

An essay from the book American Prospects by Andy Grundberg

“It is not, then, merely to satisfy curiosity, however legitimate, that I have examined America; my wish has been to find there instruction by which we may ourselves profit.”

—Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America

Why is there such an urge to encompass America—at least that part of the North American continent that is the United States? Why this drive to swallow the country whole-- to know it as one knows a lover, to reveal its innermost essence—when it was born of many parts, a federation of different states place and mind? Perhaps it is the vastness of the undertaking that draws us in, the immensity of the task. Perhaps it is the ineffability of this country, its significance so great that it invites description even while it defies it. Or perhaps it is because America is really a mirror, and in the process of describing it we cannot help but describe ourselves. If this is the case, what is at issue in books about America is not just the quality of observation, but the construction of history.

When Tocqueville disembarked in New York in May 1831, he was by no means the first foreigner to come to America seeking to discern its meaning through direct observation. He was merely more perceptive than his predecessors, and in the nine months that he and his companion, Gustave de Beaumont, journeyed across the breadth of the adolescent United States, he observed its character and prospects with an uncanny prescience. So keen, detailed, and balanced is his report, ambitiously titled Democracy in America, that it seems at times almost photographic.

Photography, of course, was yet to be born, so we have no snapshots by Tocqueville to compare his view with what we, more than 150 years later, can record today. But we know that from the moment he set foot in this country, the young French noble man was made aware that in America things are not what they seem:

“When I arrived for the first time at New York, by that part of the Atlantic Ocean which is called the East River, I was surprised to perceive along shore, at some distance from the city, a number of little palaces of white marble, several of which were of classic architecture. When I went to to the next day to inspect more closely one which had a particularly attractive my notice, I found that it's walls were of white-washed brick, and its columns of painted wood. All the edifices I had admired the night before were of the same kind.”

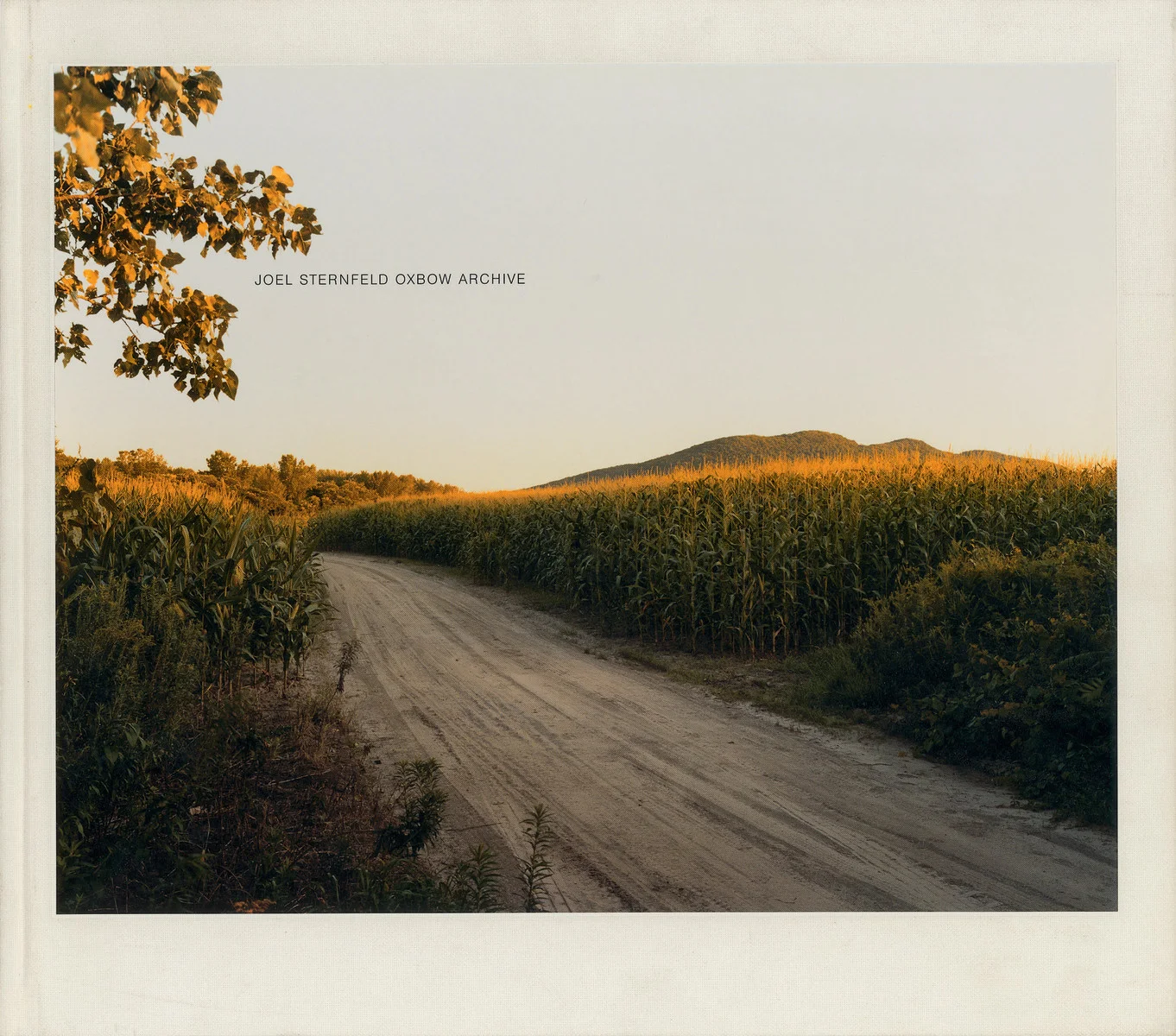

Thus did Tocqueville learn, early on, about the American penchant for putting up fronts, for keeping the best face on things, for disguising our own rudeness and cultural naïveté. This is true not only in our architecture, which again today borrows from classical models, but also in our social fabric. Here is the challenge for photographers who would picture the true face of America: how to unmask the superficial appearance of the thing, revealing not only what its people have taken such pains to conceal, but also why.

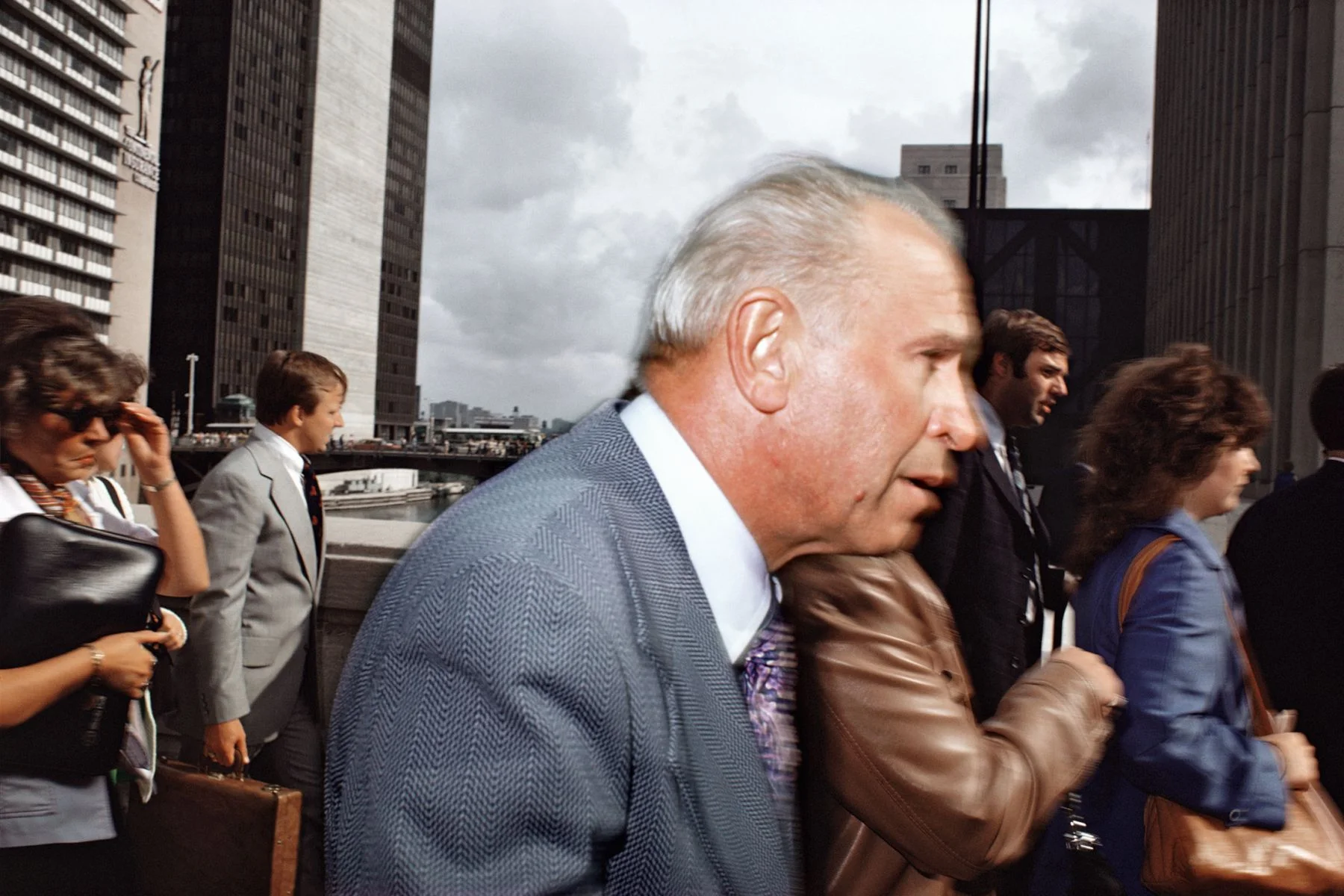

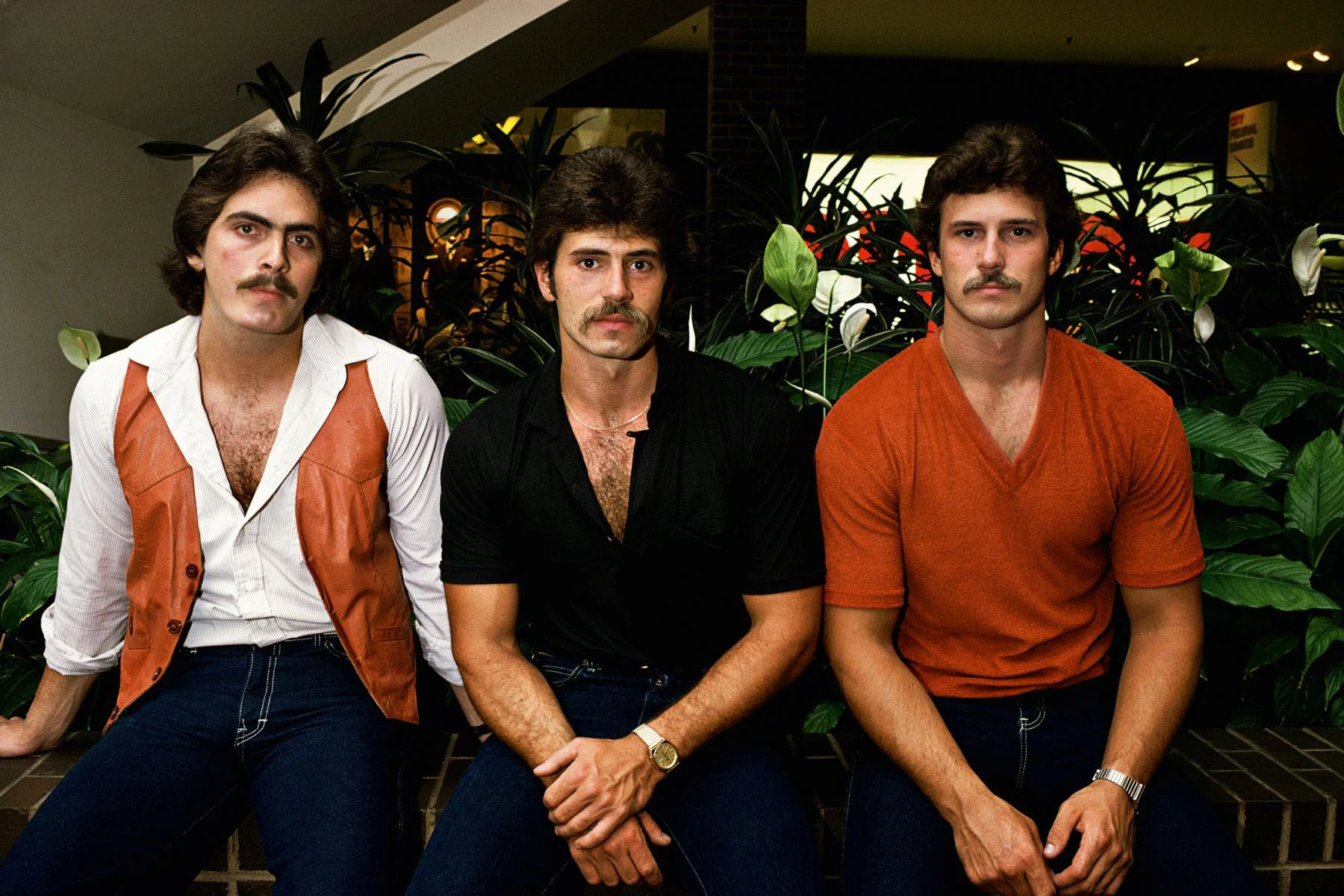

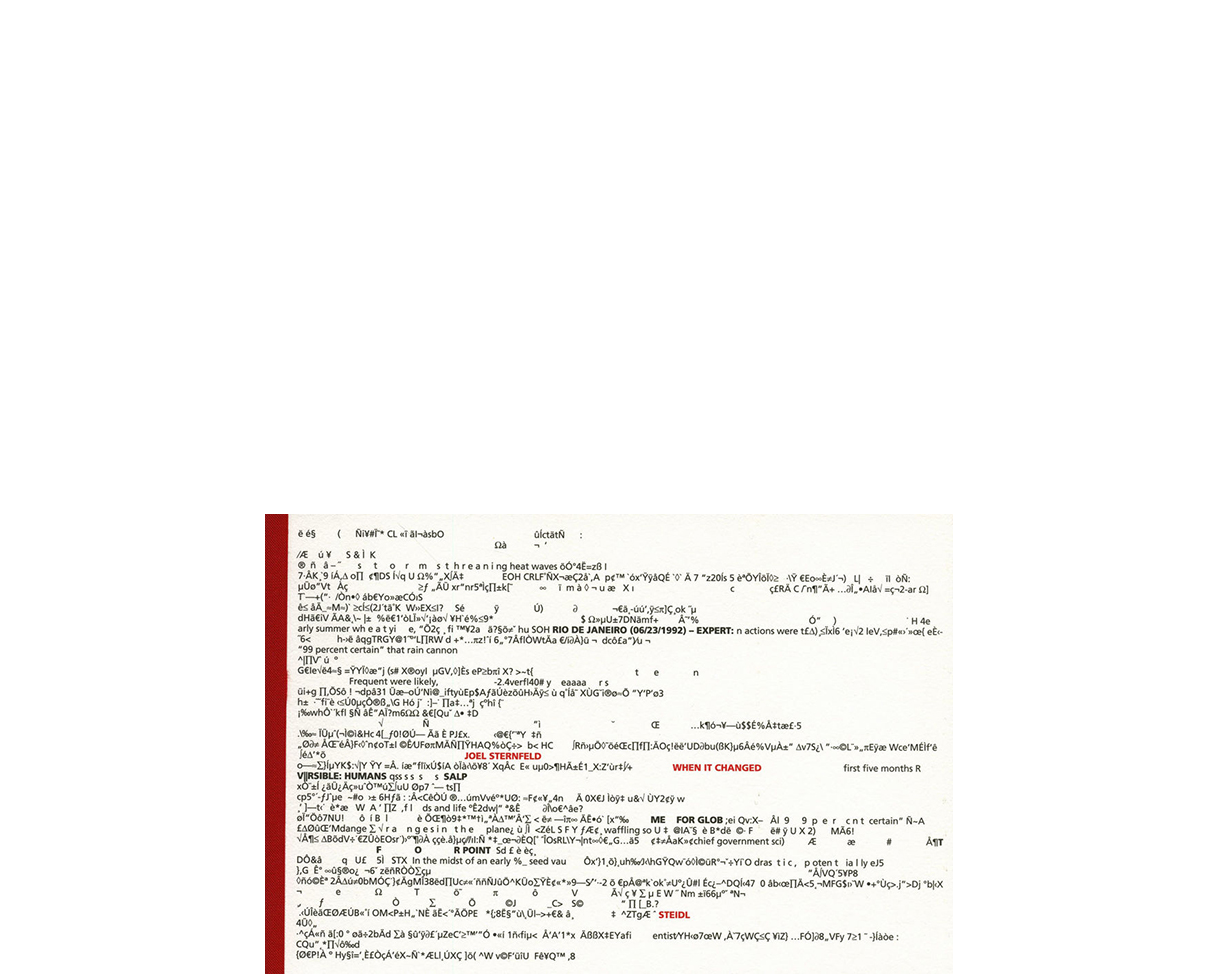

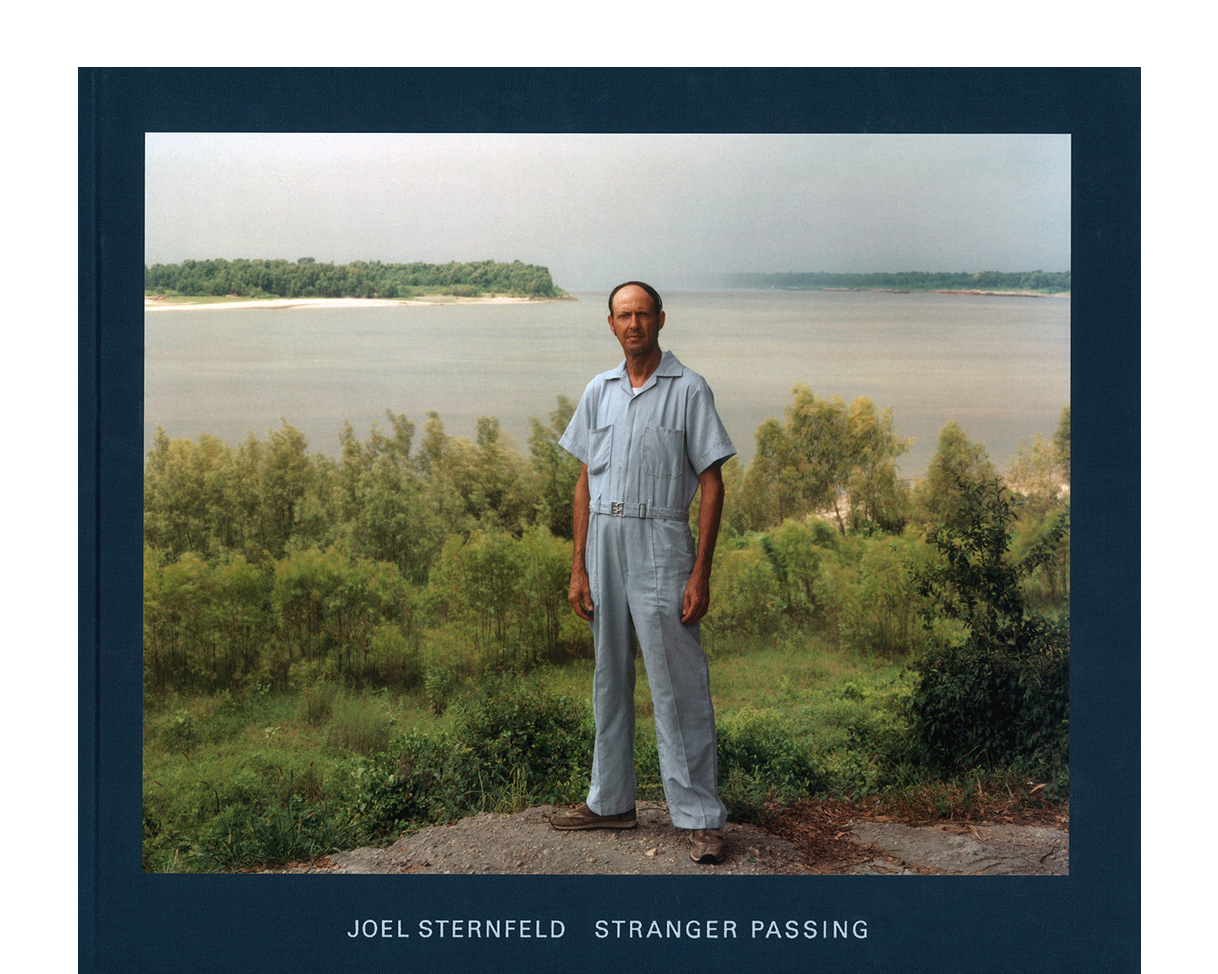

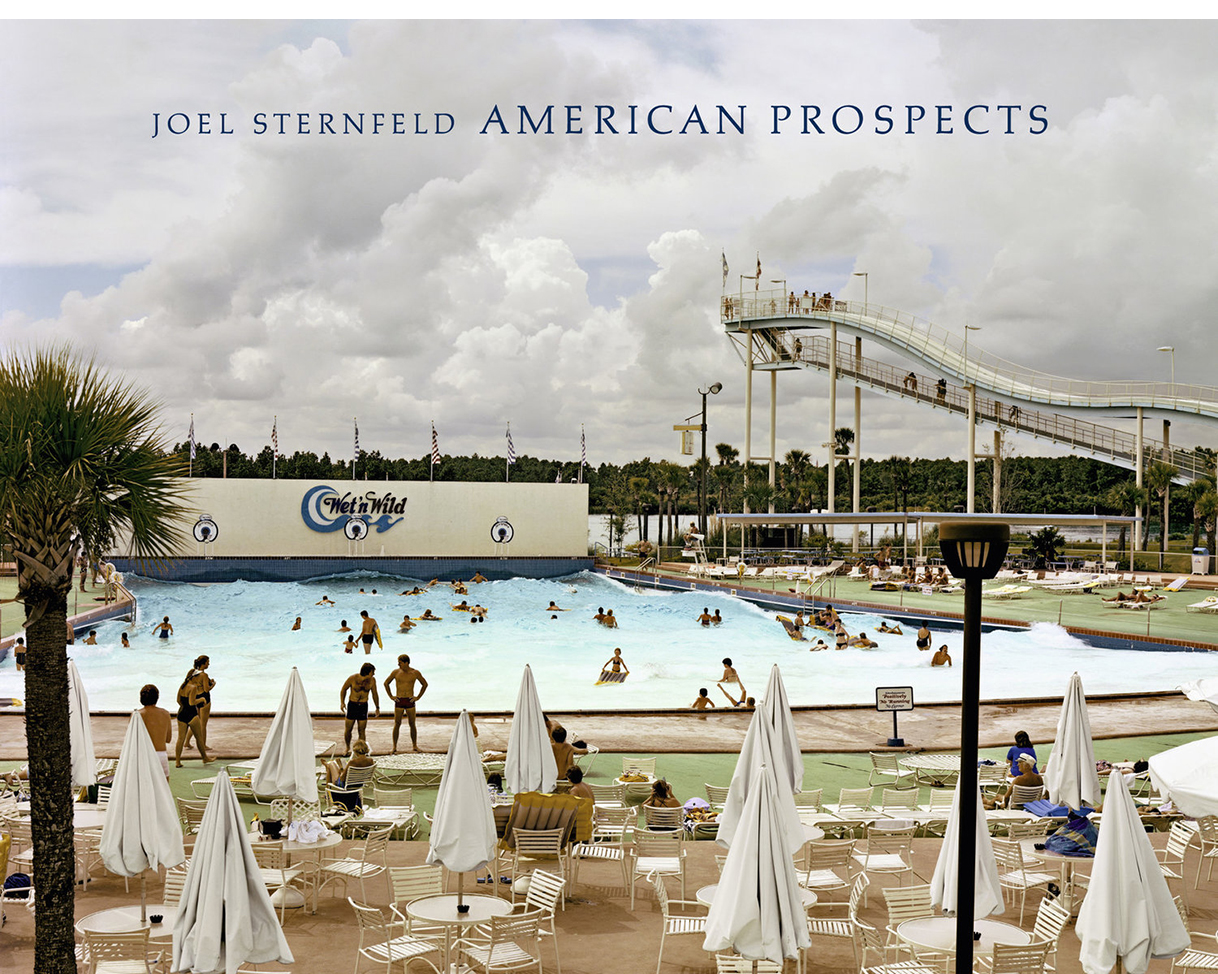

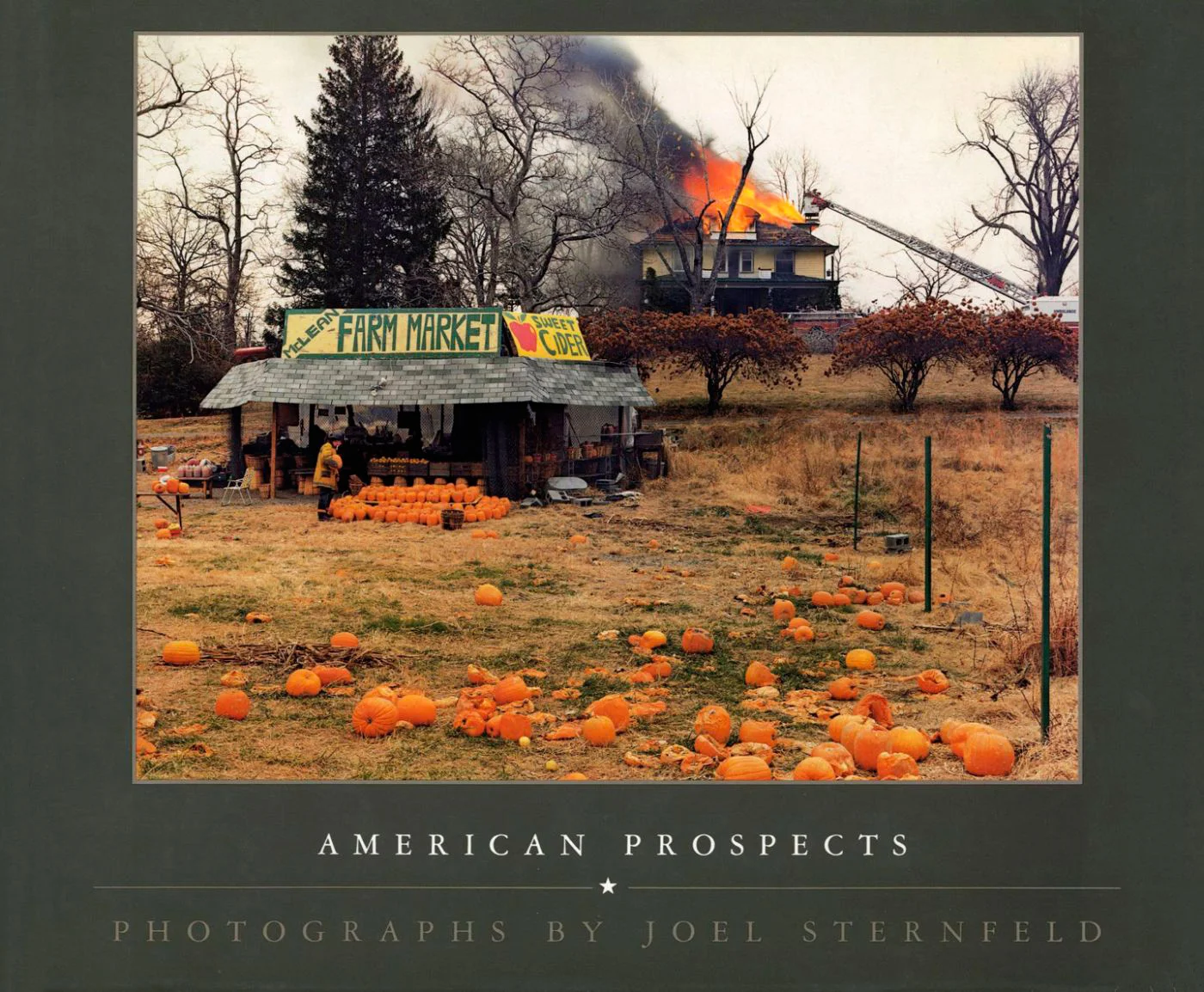

The surreal tingle that Tocqueville experienced in his first deep breath of The United States reappears in Joel Sternfeld's photographs, which take up the issue of the appearance and reality in American life from a vastly different perspective. Sternfeld’s photographs, for one, provide a native-born American view. Yet they sometimes seem so wide-eyed and ingenuous they could have been taken by a visitor from another country, if not another planet. (Then again, what distinguishes a New Yorker’s view from a Frenchman’s in, say, Bear Lake, Utah, is a matter of semioticians.) Sternfeld's pictures explicitly address the surface of things, not their underlying structure, although they certainly have much to tell about what the Reader’s Digest calls “life in these United States.” And they survey a different present—not an early nineteenth-century society poised on the cusp of industrialization, but a postindustrial, service-oriented society devoted to technology, consumer spending, personal narcissism, and increasing unemployment, which masquerades as leisure time. Of such materials are surrealists ironies made.

To discover the truth about America: the pilgrimages made in the name of this unquenchable thirst are legion, and account for a whole genre of American art, both visual and literary. It is in this tradition that Sternfeld’s photographic prospectus stands—the tradition of wanderers like Huckleberry Finn and Sal Paradise. It means, both literally and figuratively, being on the road. “Whither goest thou, America, in thy shiny car in the night?” Carlo Marx says to Sal and Dean Moriarty in Kerouac’s picturesque novel On the Road. Or as Huck Finn concludes in Twain's classic, “But I reckon I got to light out for the territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally she's going to adopt me and sivilize me, and I can't stand it. I been there before.” To discover America is to discover oneself.

In American photography, the tradition owes a debt to the exploration of the Western territories in the years following the Civil War, the government-sponsored surveys saw the virtue of employing a picture man to supply evidence of what the West looked like. These adventurers/photographers–Timothy O’Sullivan, Carleton Watkins, William Henry Jackson, William Bell, A. J. Russell–brought back dramatic landscapes, to be sure, but they had a little of the endearing effects of Hudson River School paintings. Their nature was raw, rugged, and unforgiving, and their pictures amazed contemporary audiences largely because of the inhospitable vastness they depicted. The West, in photographs, was not what it seemed when described in words or paint.

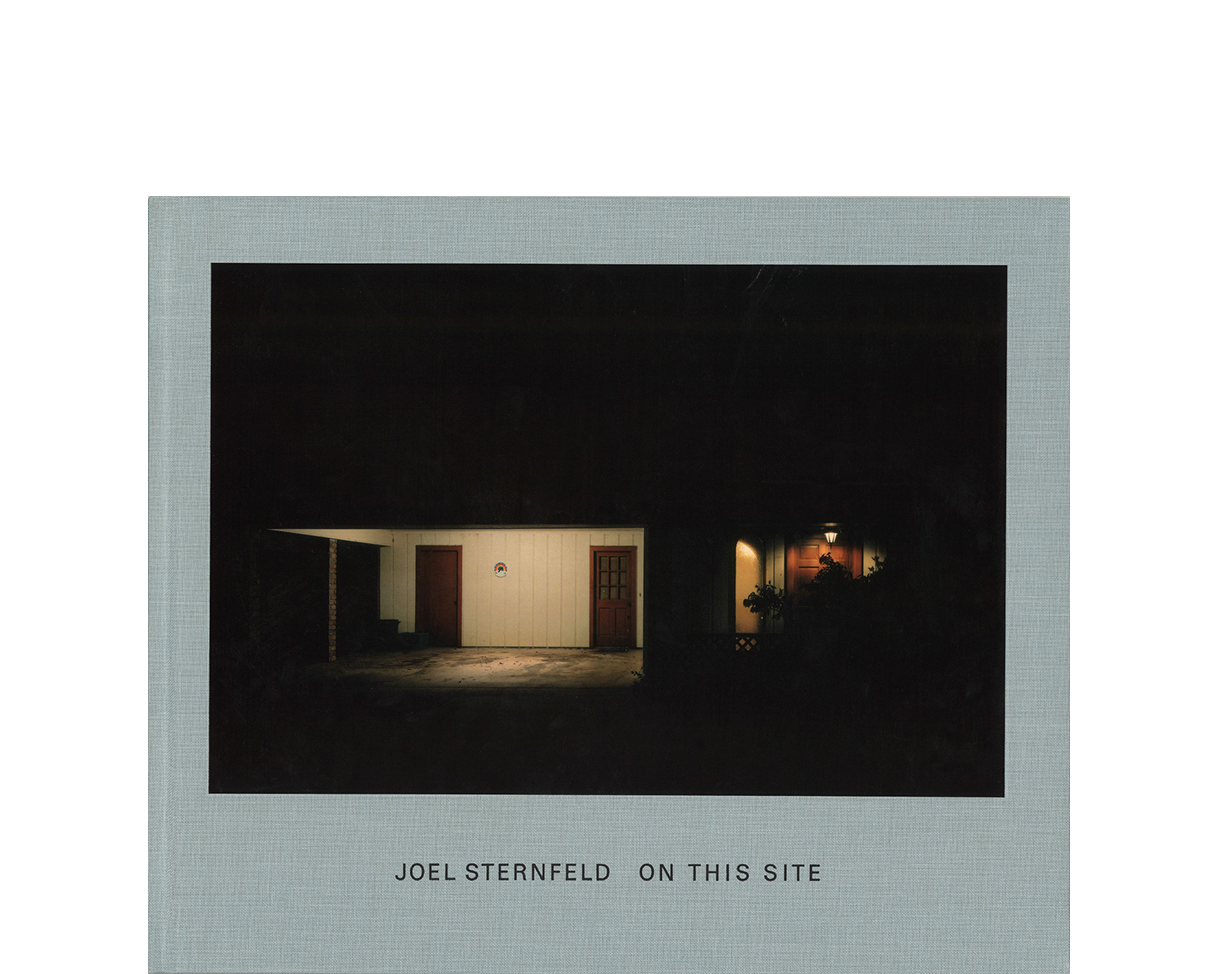

"You road I enter upon and look around, / I believe you are not all that is here, / I believe that much unseen is also here," Walt Whitman sang in his grand ode to America, Leaves of Grass. With the railroad, and soon highways, the continent lost some of its forbidding quality, but the lanes crossing the country whetted ever larger appetites for adventure. As automobiles, billboards, and Coca-Cola signs became commonplace in the twentieth century, photographers taking to the road could no longer ignore them. It was Walker Evans who first demonstrated, in American Photographs, that the elements of roadside America–signs, telephone wires, even the road itself–could be transformed by the camera into a coherent, meaningful visual amalgam. Even more significantly, Evans changed the key of the American experience from major to minor. American Photographs is a fond, measured, and ultimately bittersweet elegy pre-Interstate, pre-suburban, pre-agribusiness America. Hard on Evan’s heels came others, Edward Weston and Wright Morris among them, eager to sift nostalgia from the shards of American innocence.

Even more bleak is Robert Franks The Americans, a masterpiece that charts the face of postwar American society. Frank, a Swiss, did not come to this country to charm us, and eighty-three photographs that constitute his journal of cross-country travels home in on the tenderest of our sore spots: racism, alienation, the substitution of media-generated images for reality. Where Tocqueville saw America as the model for the future, Frank saw it as a dead-end. “A sad poem for sick people,” one critic called the book, perhaps not realizing what he was saying. Today's territorial surveys are no less sad, if more sympathetic: Robert Adams’s From the Missouri West, Lewis Baltz’s Park City, Lee Friedlander’s The American Monument, Steven Shore’s Uncommon Places.

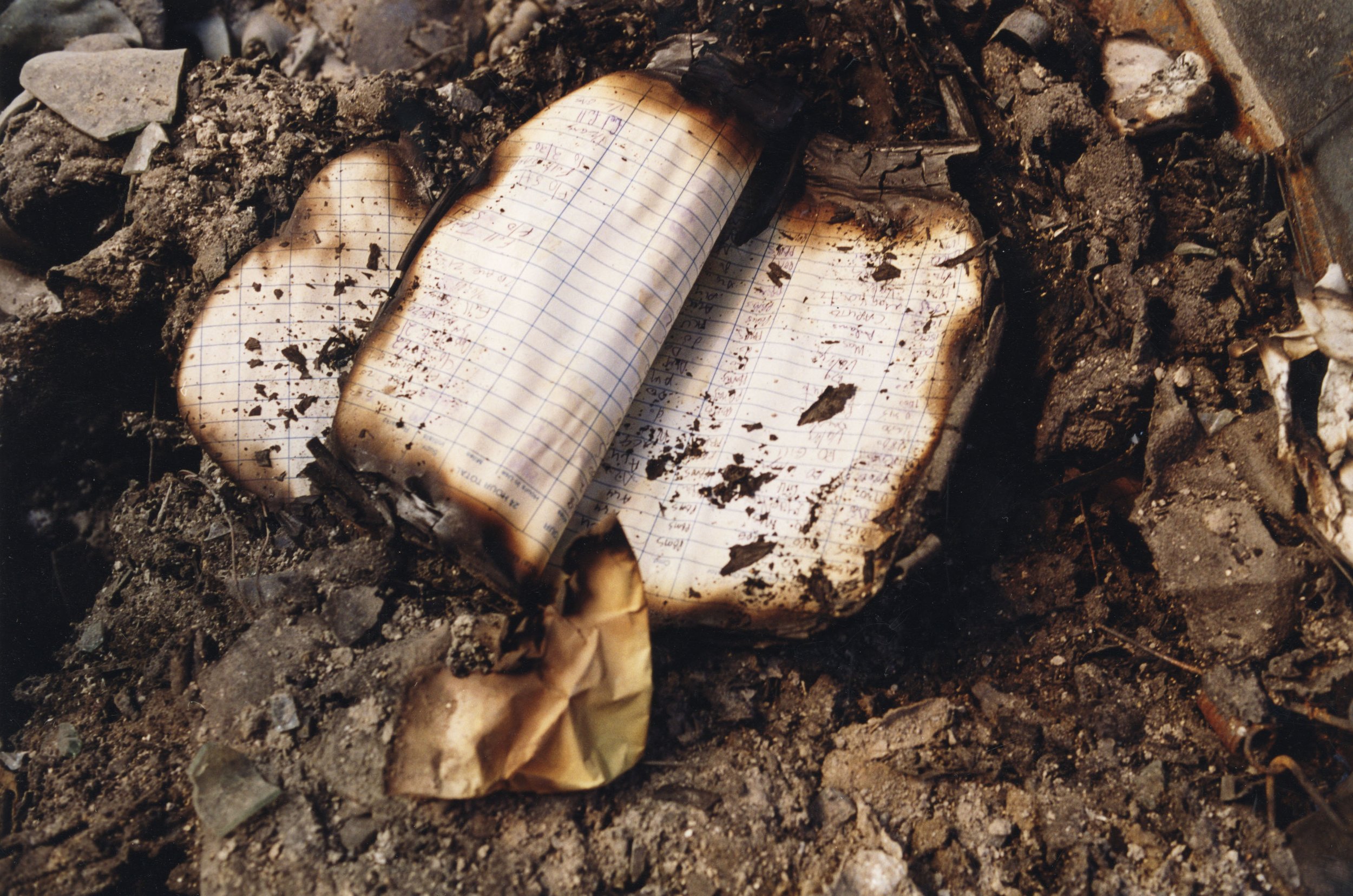

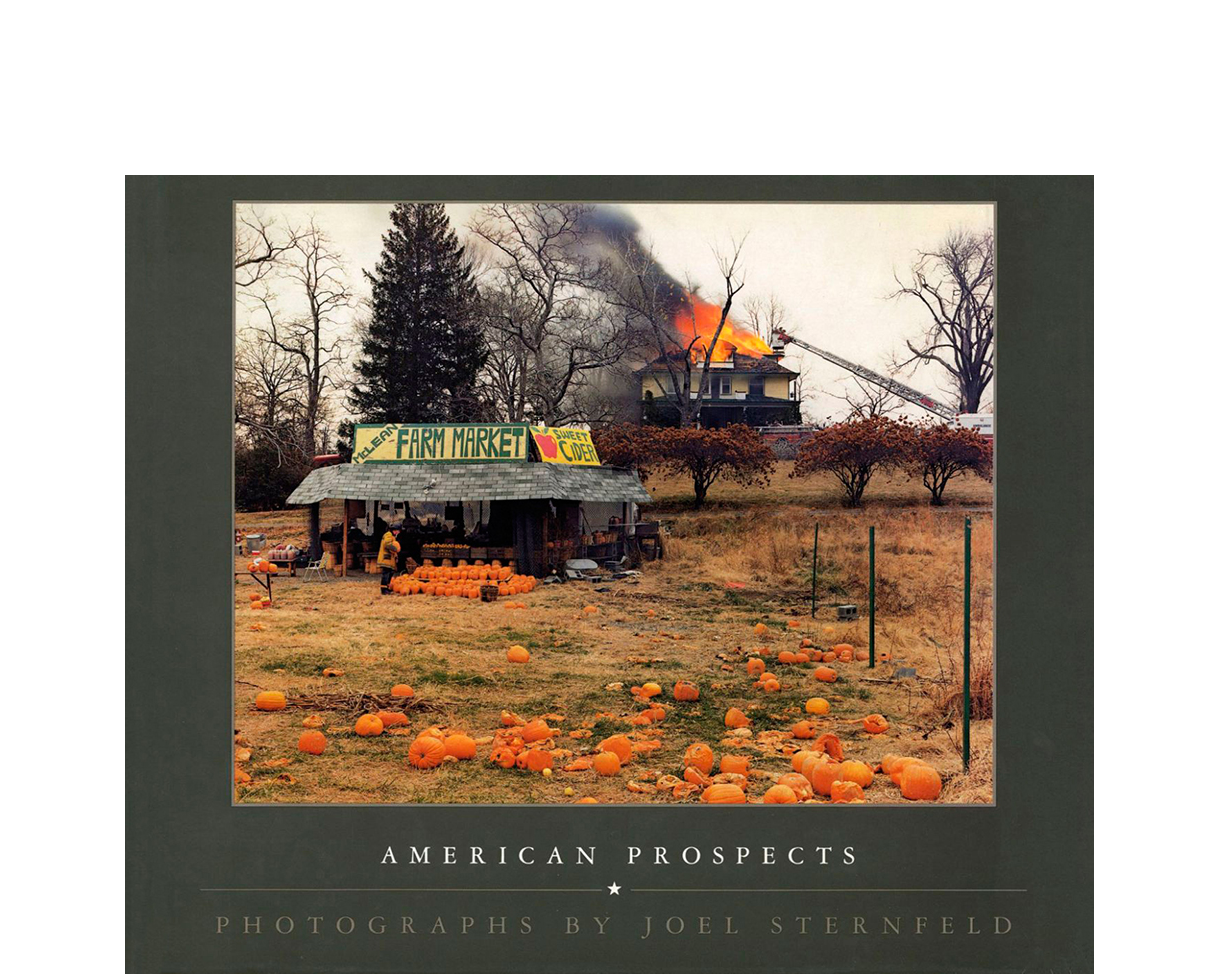

Such is the company in which Sternfeld’s American Prospects finds itself, a prisoner, like the rest, of the historical moment in which it is born. But it is more than just another sad poem, I think, for like the best of its peers and parents it fights hard to balance indignation and consolation. Those rusted coal cars, that basketball hoop poised near the Grand Canyon, the streaked faces of the rainbow chasers whose pots came up empty outside of Houston–for all that these speak of malaise, they also speak of endurance. Like the seasons, which provide a counterpoint to Sternfeld’s prevailing discourse of dissipation, the relations of man to nature and of man to man seem subject to renewal. That, at least, is the promise of these pictures, and their solace.

Sternfeld’s photographs can be funny, in a way that photographs seldom are, especially photographs taken on the road with the sense of mission and urgency. Perhaps it is a humor born of despair, a Catch-22 sense of the absurd, but nevertheless it serves to entice the eye to engage the images’ complex meaning. What seems so amusing at first glance–an elephant in the middle of the road, being tugged by Lilliputian-sized humans–resolves into the focus of the picture’s poignancy: a wild spirit, yearning to be free, is ensnared by civilization, like Huck Finn in the grasp of Aunt Sally. Elsewhere, much is folly: the fireman shops for pumpkins while a house burns. The jokes are false fronts, marvel made of brick and wood. Yet in such discontinuities, Sternfeld’s pictures suggest, lies the essence of America’s present.

No wonder, then, that evidence of America's rural and industrial past leaks into his photographs, as well as the signs of its technological future. They are connected by the thread of their incursions on the landscape of today. As views in the nineteenth-century tradition, the images contain such a diversity of information and feeling that we can overlook their inherent didactic qualities. The photographer’s eye is generous, understanding, and forgiving, but it is also critically aware, intelligent, and unblinking. Fortunately, this combination has created a suite of pictures as dense and meaningful as they are beautiful.

In the future, no doubt, these images will seem suffused with nostalgia, much as we now see you Walker Evans’s photographs of the 1930s. They will seem less ironic and more totemic, and their sometimes acid social commentary will lose much of its bite. But for now they speak of a time when progress lost its sense of inevitability, when the lands lost its last pretense to innocence, when the spirit of individualism flickered for want of fresh air. They also speak of nature's restorative powers, of human goodness, of men and women seeking to accommodate their primal needs to the imperatives of technological society. It is a tricky business, balancing these messages, and it does not make for ideological simplicity or political instrumentality. However, in these photographs Sternfeld manages to eke a measure of harmony out of in assortment of follies, which makes American Prospects a metonym for the state of our times.