A Walk on the High Line

An essay from The New Yorker by Adam Gopnik

High is to New York what wet is to Venice— the necessary condition that has become the romantic condition. To be up, and above, those still felt as imprisonment in too many office-closeted lives, can, with the addition of a breeze or an eccentricity, become an escape, a source of renewal, and even provide a feeling of belonging. In Manhattan, to look down is not always to look down on. It is a communal experience, with something of the feeling of sailors and the crow’s nest looking at other sailors, a fellowship of the air—not avoiding the storm, exactly, but at least sharing the news of it early. Moguls in the spires of skyscrapers stare at other moguls, and millionaire actors wave across the Park at other millionaire actors, and tourists go to the top of the World Trade Center to gaze with binoculars at tourists in the crown of the Statue of Liberty, and, if people crowd the Brooklyn Bridge, it is not to jump but to admire the falcons’ scrape on one of the towers, an enviable home up high. When Superman is spotted in the sky above the city, people think mildly that he might be something else, a bird or plane… The archeology of Manhattan is reversed: the past and not buried in the ground but held up in the air, on the upper floors. You see old things clearly: ghostly unlit Longchamps signs and forgotten Deco-Aztec metal detailing and abandoned penthouse night clubs. In New York, the overhead viewpoint is curiously peaceful and nostalgic—the beautiful vista, rather than the sublime. (The sublime vista is subterranean—the No. 6 train approaching the Fourteenth Street station through the gloom, eyes on fire.)

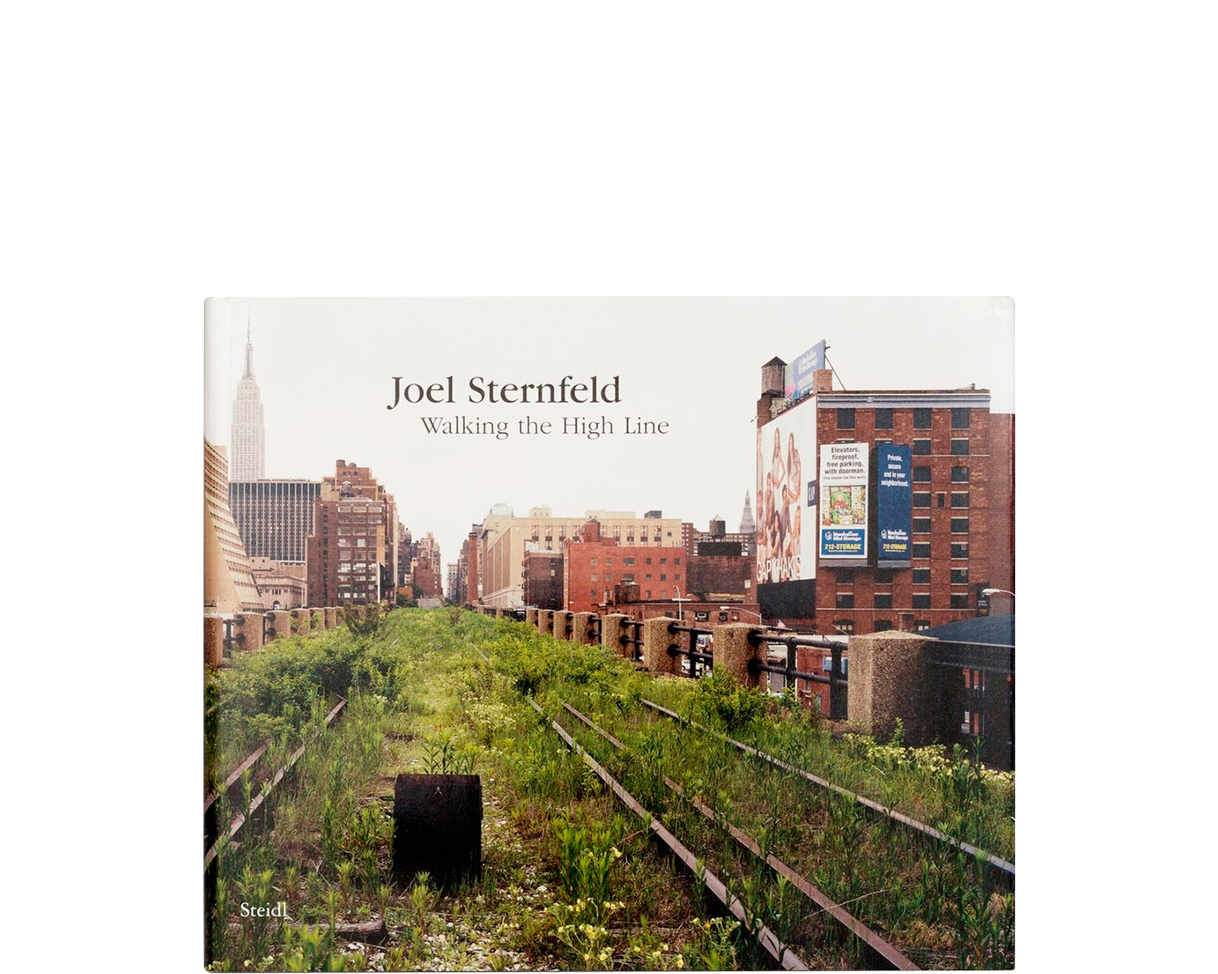

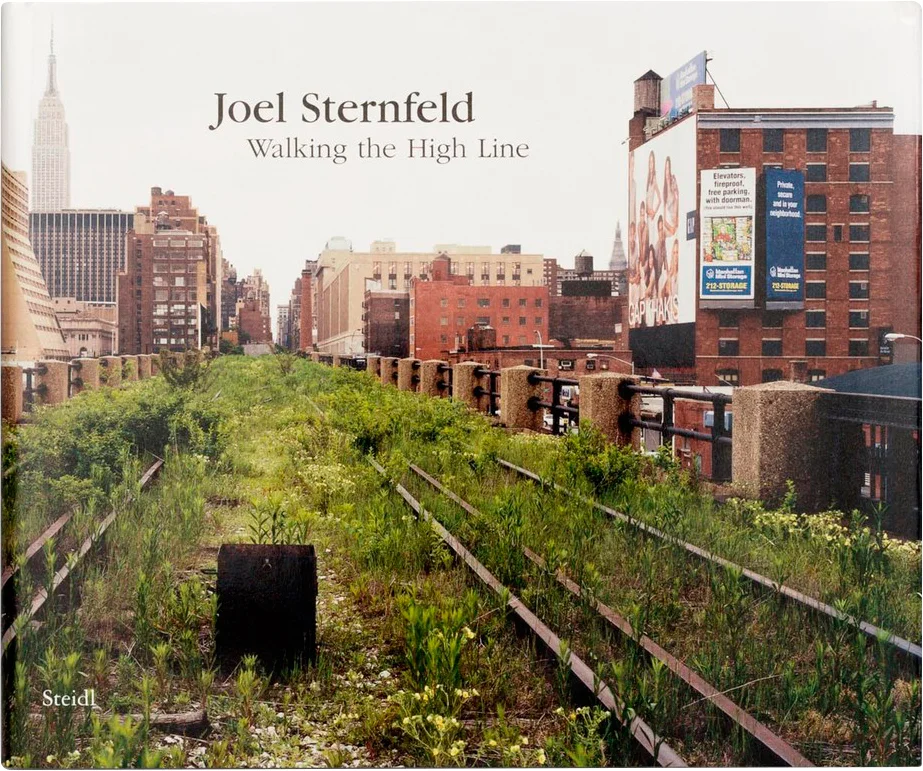

The most peaceful high place in New York right now is a stretch of viaduct called the High Line. The High Line is a derelict elevated railroad track, about two stories high, running a mile and a third along the western edge of the city, from Thirty-fourth Street to Gansevoort Street. It encloses about eight acres, or half a million square feet, of taffy pulled, thirty-to-fifty-foot-wide horizontal space. Many people who pass under it think that it is an old El track. In fact, it is, or was, a New York Central Railroad track, used for fifty years to convey goods from all over America to little shunting among the West Side warehouses. For more than two decades—ever since the last three carloads of frozen turkeys made their transit to Gansevoort Street—it has been under a provisional death sentence, condemned by the property owners caught in its shadow. But one thing or another has kept it from being torn down, and, just recently, it has become a gleam in the eye of some West Side do-gooders, who call themselves the Friends of the High Line, and who see it as a potential midair park. The Giuliani administration has been hostile to the project— the Mayor’s men apparently viewing it as exactly the kind of touchy-feely, hey, kids, let’s make that broken-down railroad into a park! Upper West Side quixotism that would leave the whole city carpeted with moss if left unchecked— but a lot of other local pols, topped off by Senator Clinton, are all for it.

For the moment, the High Line has gone not to wrack and ruin but to seed: weeds and grasses and even small trees sprout from the track bed. There are irises and lamb’s ears and thistle-tufted onion grass, white-flowering bushes and pink budded trees and grape hyacinths, and strange New York weeds that shoot straight up with the horizontal arms, as though electrified. A single, improbable Christmas tree can be found there, and a flock of warblers have made themselves a home, too. In one sheltered stretch between two tall buildings is a stand of hardwood trees. The High Line combines the appeal of those fantasies in which New York has returned to the wild with an almost Zen quality of measured, peaceful distance.

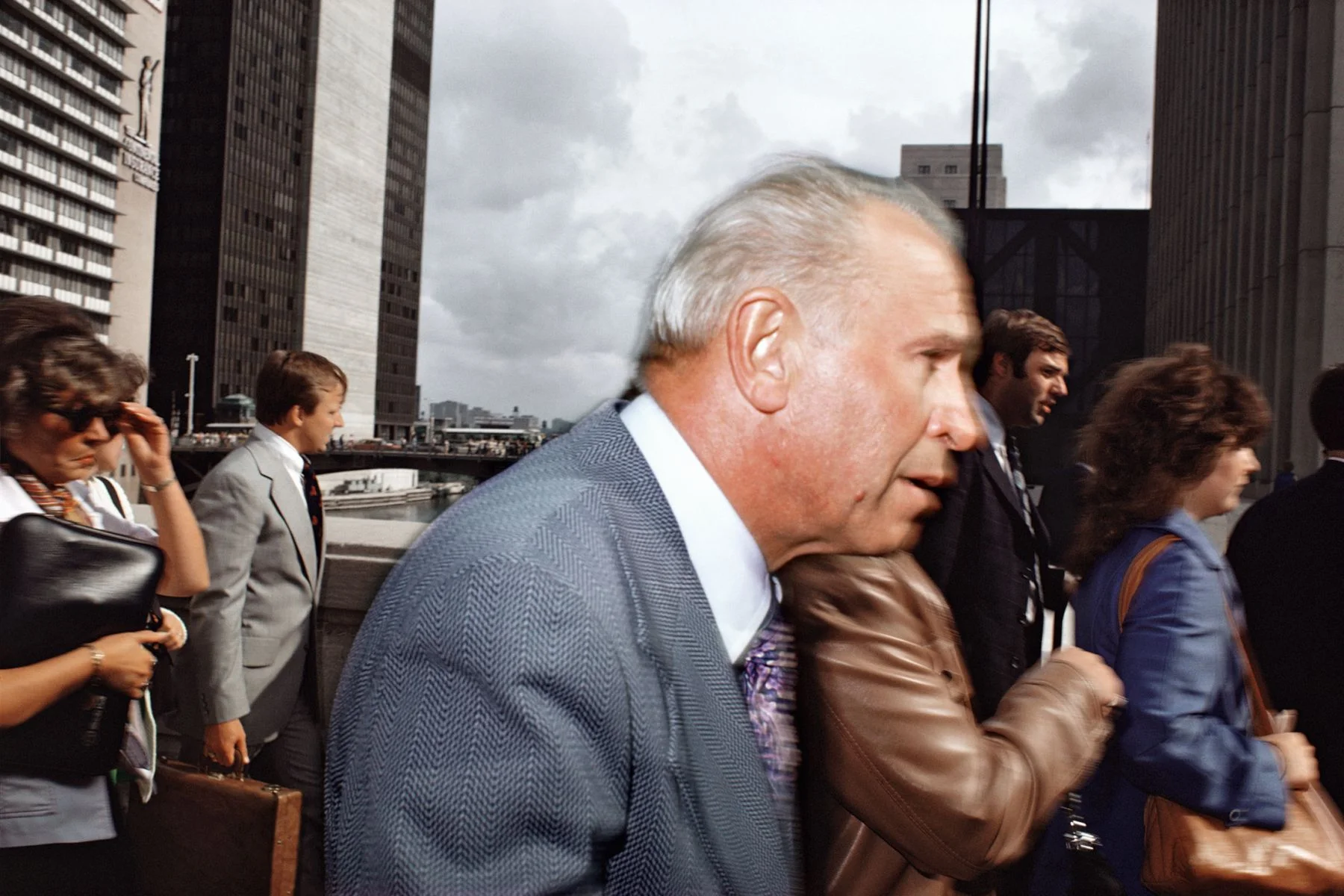

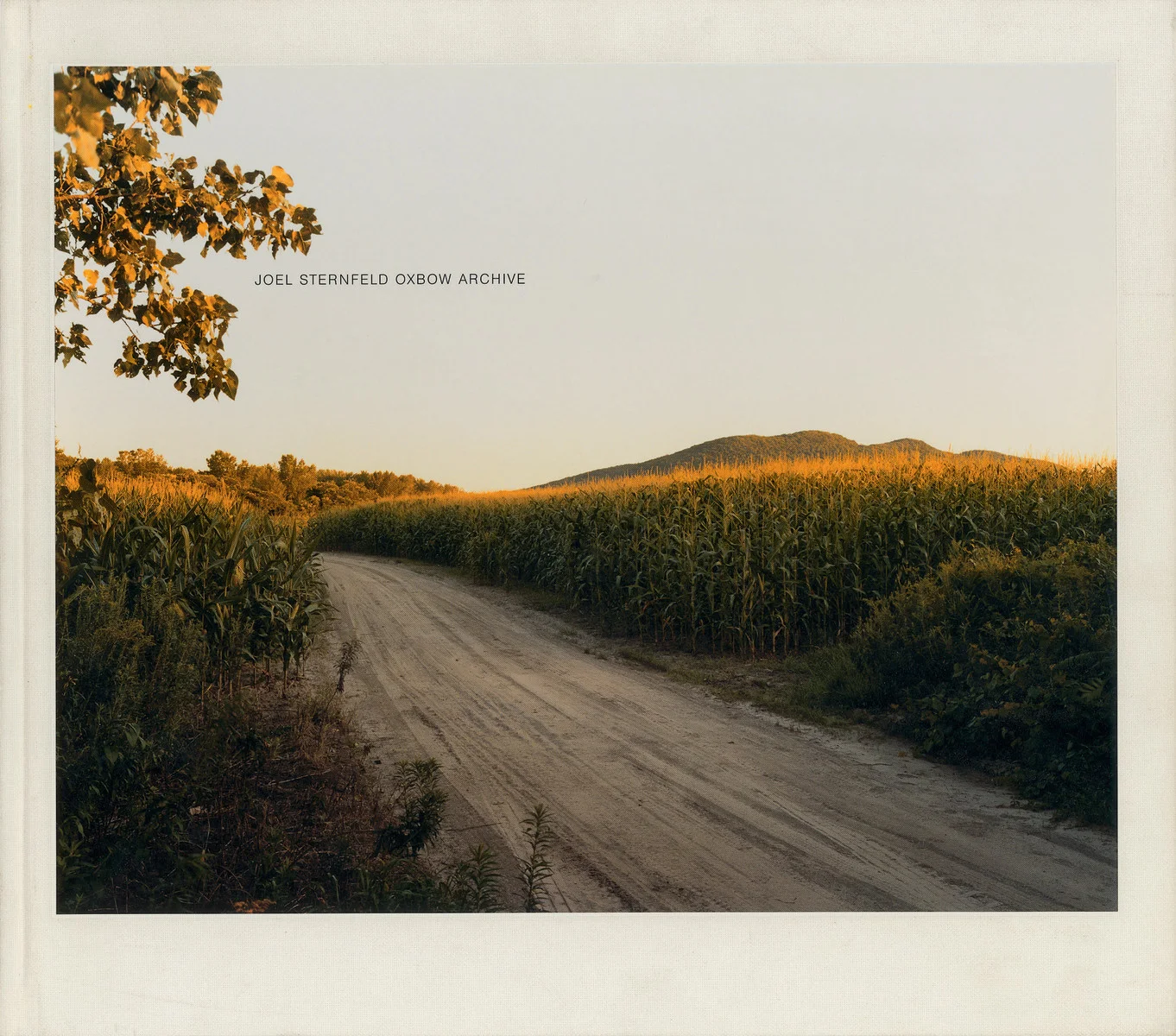

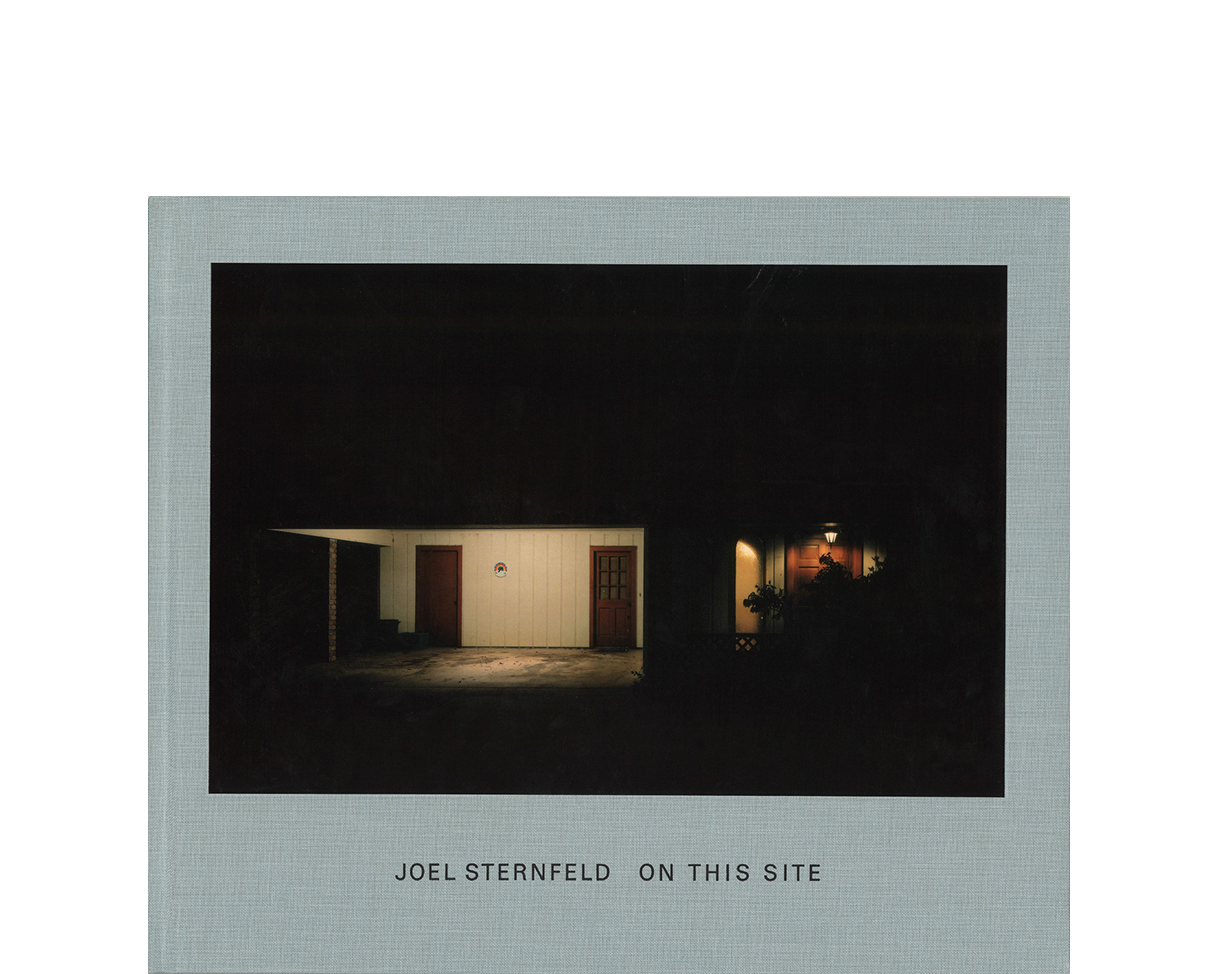

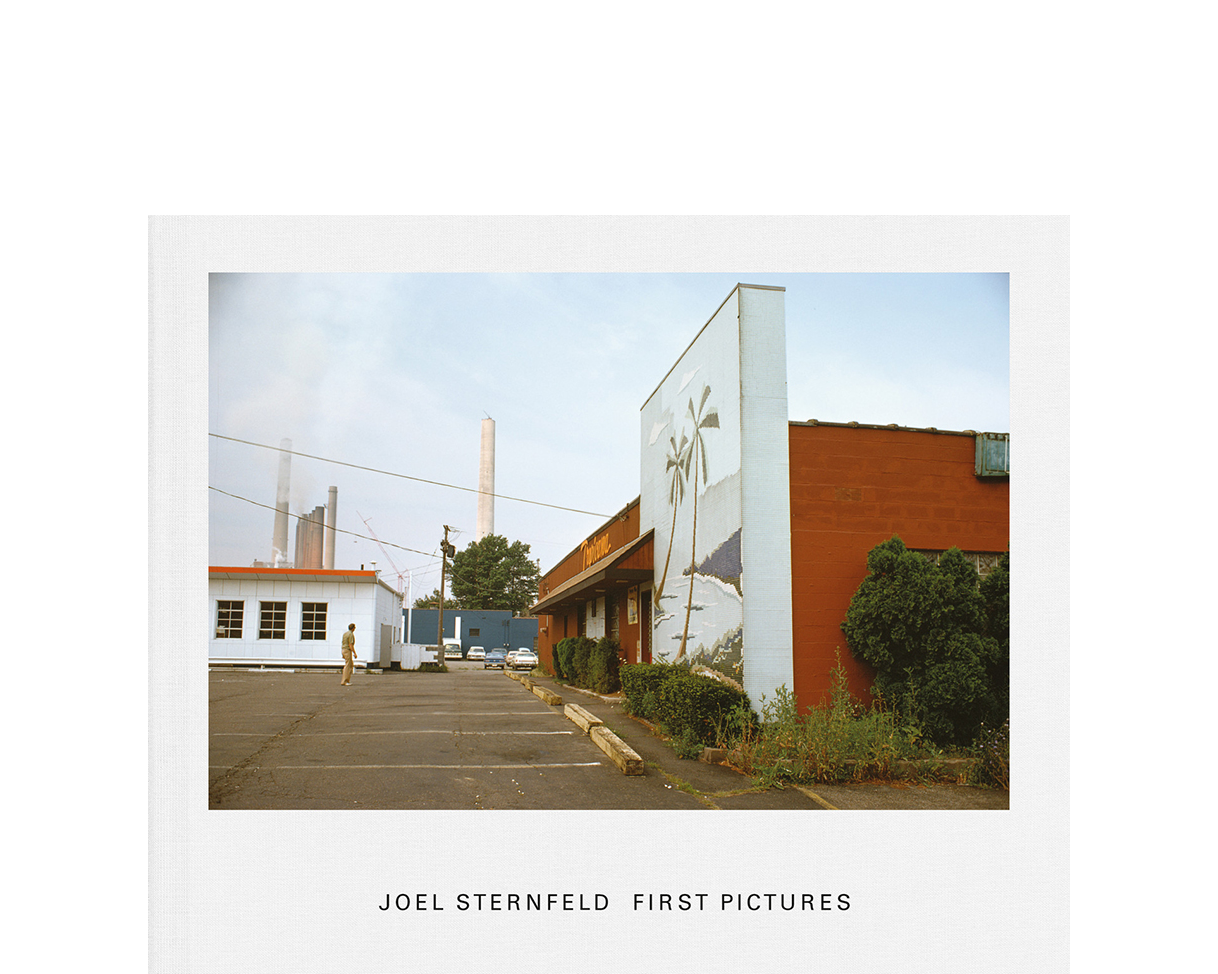

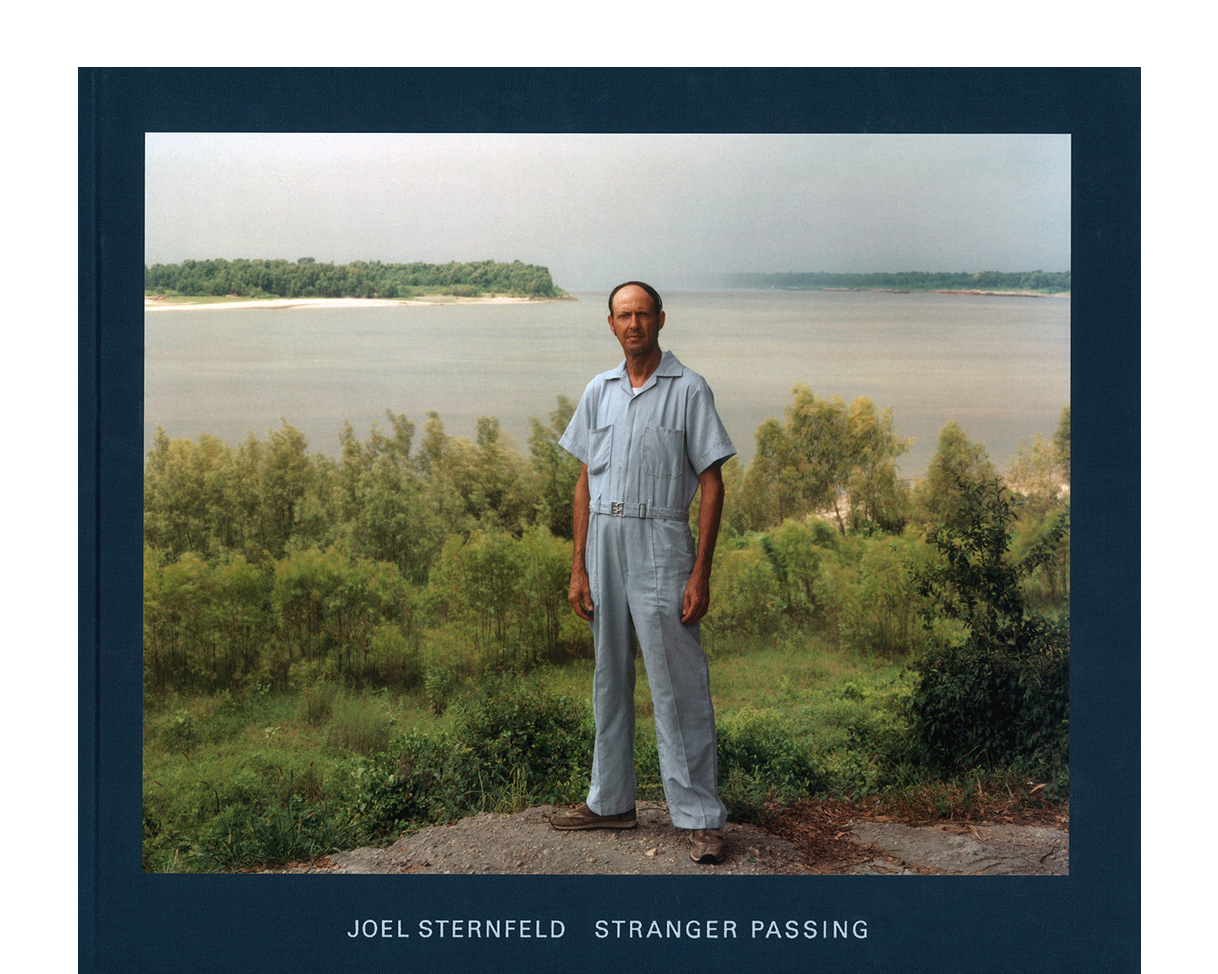

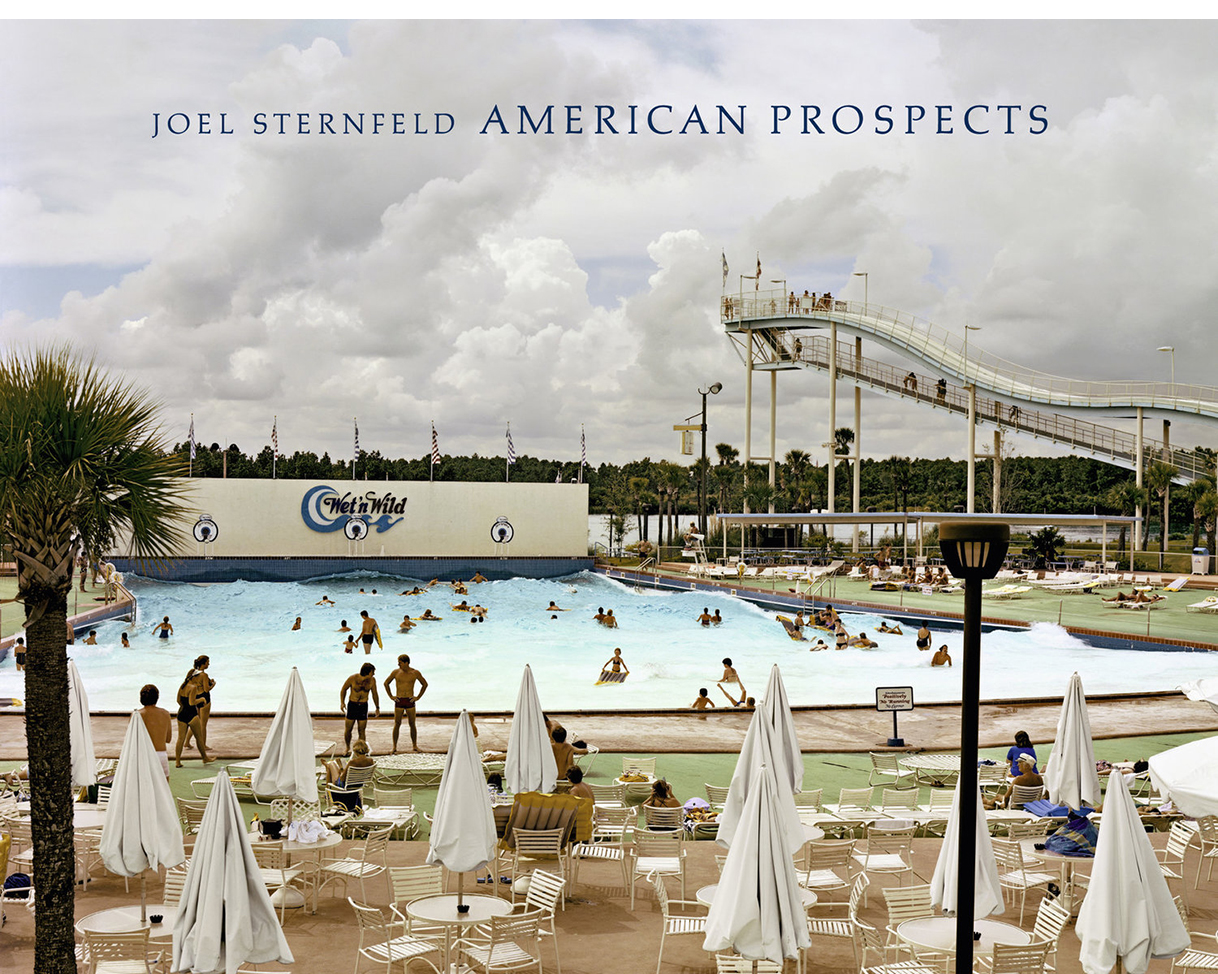

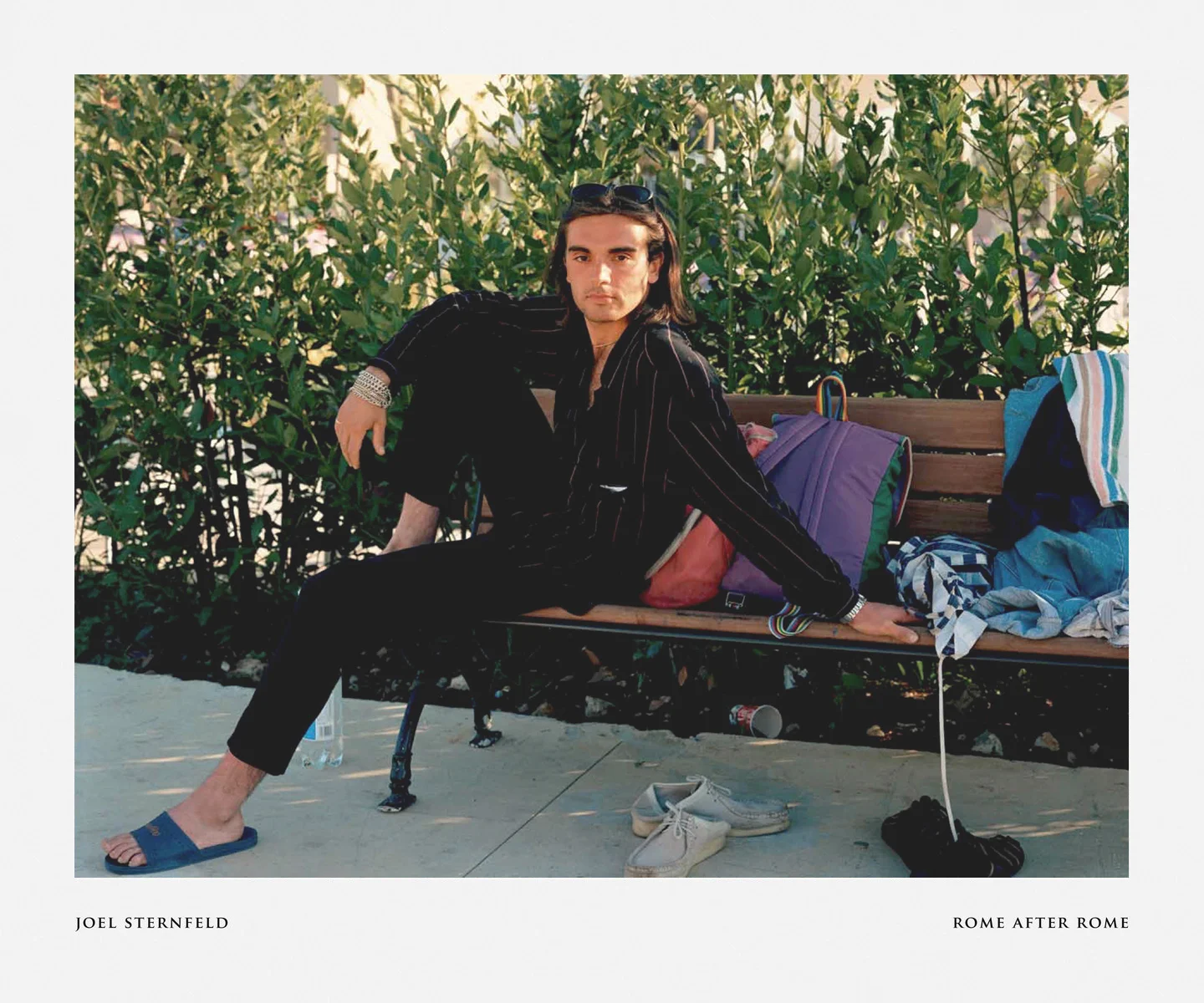

The poet-keeper of the High Line is the photographer Joel Sternfeld. He has been taking pictures of it in all seasons for the year, and he has a gift for seeing light and space and color— romantic possibility of every kind— where a less sensitive observer sees smudge and weed and ruin. He would not just like the High Line to be saved and made into a promenade; he would like the promenade as it exists now to be perpetuated, a piece of New York as it really is. Where many of the High Line’s supporters see it as potential—they are not averse picturing, in imagery that evokes the airy, weightless, jaunty style of an architect’s rendering, picnic tables, and monorails and sculpture parks—he sees it as a thing already accomplished, and wants to keep it more or less as it is.

“It’s more of a path than a park,” he said one recent afternoon at the beginning of a traverse. “And more of a Path than a path.” (He makes caps with his eyebrows.) Several times a week, he lugs an immense, Mathew Brady-style eight-by-ten camera, complete with black silent-movie-comedy cloth, up to the tracks and, pulling it under fences and through sidings, records the High Line’s moods and light.

“Central Park,” he went on as he set up tripod and camera facing the river, to take a study of a chimney, beautiful in grayish afternoon light, the stands starkly by the side of the tracks, “is really cosmetic in many ways. This is a true time landscape, a railroad ruin. The abandoned place is the place where seasonality resides. These little shoots—see this! This is the real look of spring. Central Park is a construct in so many ways. A beautiful construct, but made for an effect. This” —-he gestured around the old track bed— “is what spring in New York actually looks like when its left up to Spring.”

Spring in New York looks like this: low grasses and weeds abound at shoe-top level and tawny grasses are folded over on each other, like winter wheat. The onion grass gives an acid smell if you get down close, and clover lends a sweetness. Knee-high plants that look like tarragon grow in neat rows and, as you look east, seem to enter into a distinct, perspective-keeping compact with the canyons of the Thirty-first and Thirtieth Streets, whistling away toward the East River. It is quiet there, and the Hudson, which fills the vista the opposite, or western, direction, suddenly seems not a distant rumored presence but the obvious point of the joke— the reason people settled this island in the first place. It is a mirror bouncing off light and provoking breezes.

The High Line does not offer a God’s-eye view of the city, exactly, but something rarer, the view of a lesser angel: of a cupid in a Renaissance painting, of the putti looking down of the Nativity manger. That little height makes even ugly thinks below look orderly and patterned. From the first section of the High Line, you see the cars of the L.I.R.R. commuter trains, waiting; a man’s voice, immense on a speaker, occasionally breaks the silence, calling out track numbers. On a ramp in the middle distance four trucks are parked, with enormous slanting letters offering this reiteration: RELIABLE, RELIABLE, RELIABLE, RELIABLE. In the far distance, a small building says O/V/E/R/S/E/A/S, each letter carefully painted beside a window, and, up above, DIAL JOE/1234. Alongside, a vast, low Federal Express depot sweeps away, the brutal lavender-and-orange FEDEX its only inscription. (It looks smugly back at its little shipping neighbor, as if to say, “Dial Joe? You gotta be kidding, I mean… Dial Joe?”)

“It’s a history of suppression, all visible,” Sternfeld says. “First this railroad, and then overseas shipping, and then Federal Express.” He was dismantling his tripod, since the picture he’d had in mind had struck a snag. The people who are addicted to the High Line, particularly Sternfeld, like to say it offers a “transporting’ experience, the experience of a pilgrimage more than a promenade; it doe shave a mythical aspect, with an Olympus in the Starrett-Lehigh Building, which looms, vast and glassy, to the west, and the superintending presence of two enormous goddesses who look calmly down— one, its recessive Artemis, advertises the clothes of the Gap, the other, farther on, is Aphrodite, splayed out on a chair, and beckoning the pilgrim from the path on behalf of of the Guess company. Right now, the girl in the Gap ad kept getting in the picture. (She’ll take over the photograph,” Sternfeld says, with a practiced sigh. “She always does, and it gets a little obvious, you know, this world against this. A little too on the nose.”)

“You know what I’m seeing!” he says suddenly, excited. “It’s that beer bottle! It’s prominent in a shot I took last fall—and it hasn’t moved!” He walks over and, without picking it up or disturbing it, gently gazes down at the clear-glass bottle and shakes his head—amazed, like Proust, at the strange persistence of beauty in the face of time.

Now down in the city, you see: a homeless men’s encampment, laid out on a tarpaper roof. There are frying pans and boxes and big plastic tubs, and an exquisite wrought-iron chair, dragged out into the light. Someone has brought a televise dish up to the High Line and fastened it to a railing, and someone else— one of the homeless guys, apparently— has parasited on a second cable, and run it down toward the Hooverville. The enormous girl on the Gap ad looks mutely away. A small switch hotel stands just south of the rails, with its telltale roof generators and towers.

Joel Smiles. “There are no derelicts here,” he says decisively, “and no rats—what would rats and derelicts do up here?—although the people who are trying to pull it down like to say there are. There was one homeless man up here last year. But he was fanatic about recycling.”

There is a corrugated-metal fence at the end of this section of the path— why, no one is quite sure— and, once you’ve wriggled, sideways, through a hole that has been punched in it, a second, short placed section leads you to another fence. You have to crawl under that one, shimmying flat on your back.

But a surprise is waiting: a neatly ordered vista, among the grasses, of crocuses, daffodils, and tulips, and a dwarf maple and the smallest Christmas tree in the city, wrapped in lights. A white gangplank leads from the window of an apartment nearby onto the High Line. The apartment is rented, and garden kept, by a designer named Ken Robson, who lives there with his elegant, nervous dachshund, Ross. Ken has been edgily walking out, pirate style, along his white gangplank high above the alley for about five years, carrying bulbs and seeds and Christmas lights and topsoil. “You can really dig right down into it,” he says of the track bed. “It’s good for growing.”

The history of the politics of the High Line are just possible to summarize, though to do it plunges you into the New York place called the Alphabet Dimension, where government agencies and programs with strange acronyms and abbreviations award money and fight for power. In brief: When Conrail took over the New York Central, in 1980, nobody used the High Line anymore. When another rail company, CSX, acquired Conrail’s tracks east of the Hudson, twenty years later, it left the High Line alone, too. Meanwhile, local property owners, under the umbrella group called C.P.O., or Chelsea Property Owners, had pressed the government, through the I.C.C. (the Interstate Commerce Commission), to force the railroad to tear down the unused line. (It can do this, by law, if the line is derelict; this section of railroad is not, strictly speaking, property but what is called an easement in the air, which can be forcibly torn down if it is no longer in use.) In 1992, the I.C.C., which has since become the S.T.B (the Surface Transportation Board), gave Conrail a conditional abandonment order. Several tricky money question—basically, who’s going to pay how much to tear it down and who’s going to go to court if someone sues for something that happens while its being torn down—have kept the demolition stymied and the High Line up.

While this dispute was going on, a couple of neighborhood residents, Robert Hammond and Joshua David, noticed the High Line, without even knowing what it was, and thought what it might be worth saving as some kind of public space. They were surprised by how much support they received, and how many ideas—for parks and promenade—were brought forward. Fortunately for the High Line’s friends, there exists an organization called Rails-to-Trails Conversancy, that helps groups that want to take railroad lines and turn them into “recreational” areas. There are already eleven thousand miles of such trails in the country, and the High Line would be eligible for conservation. Estimates— what are known among Chelsea Property Owners as “laughably conservative estimates”—put the cost of park conversion at around forty million dollars, which is not, by the standards of a city that spends a billion and half dollars a year on environmental protection, really all the much money. Federal funds would act as seed money for the public fund-raising.

For the moment, the High Line’s friends would like to get, well, a C.I.T.U.—a Certificate of Interim Trail Use— from the S.T.B., which would save the line and let them start raising money. “We want the development of the area,” Hammond says, “but the bottom line is that this runs through three changing neighborhoods—the meat-packing district and Chelsea and the lower edge of Hell’s Kitchen—and it’s great piece of infrastructure. We just want to save it for thoughtful development. The one thing you can be sure of is that there will never be an opportunity to build again a mile-and-a-third long parkway in the sky on the West Side. If we lose it, it’s gone for good. We don’t know what it might become, but we know that if it goes it’s gone. The weird things is that the High Line is just a structure, its just metal in the air, but it becomes a site for everybody’s fantasies and projections. People see rats and derelicts where there aren’t any, or else, like Joel, who’s a visionary, they see the city the it ought to have been.”

After the garden, the wood. A small stand—hey, a glade!— of ailanthus trees has grown up, a few hundred yards or so from the little garden, in the tight shadowed space by the Wolf Building. The wood is hard, and the trees are ten and twelve feet tall. Joel has a particular affection for this part of the High Line. “I just pray that, if they save the High Line, they’ll save some of the virgin parts too, so that people can have this kind of hallucinatory experience of nature in the city.”

In the city below, you see: a junk yard rumbling and gabbling. It is an elephant’s graveyard for computers and computer parts. Whole mainframes can be seen down in the yard, awaiting the blow of the lobster claw, returning them to the metal they care from. The junk yard, or recycling center,” is neatly divided—old pipe here, electronics parts there—and three huge machines, magnet, claw, and shovel, take turns doing their work. The railing on the High Line next to the yard is gone; Joel suspects that, in a hungry moment, the claw turned, rose, and gobbled it up.

Then you also: the crowds of gallerygoers on the Twenty-fourth and Twenty-second Streets, weaving in and out of Mary Boone and Matthew Marks. Although Twenty-fifth and Twenty-third Streets look the way streets on the far West Side have always looked— a low-slung melange of taxi garages and electrical-repair shops—Twenty-second and Twenty-fourth have been transformed, two fingers of SoHo probing into the depths of Chelsea. Antonio Homem, the dapper director of the Sonnabend gallery, nips down Twenty-second on his way back from lunch, sees visitors on the High Line above, and tips his hat. A sign hanging outside a night club reads, “Be Good to the Roxy and the Roxy Will Be Good to You.”

The High Line can be traversed only to Sixteenth Street, and the old National Biscuit Company buildings, now Chelsea Market. A bank of grace hyacinths blossom in its shadow. A giant dot-com sign is painted on the side of a nearby building. Joel sternfeld assembles his eight-by-ten camera and tries to frame a picture. Gesturing toward the sign, he says “It’s a choice, the Zeitgeist or the grape hyacinth.” He turns his camera in the other direction, gets under his cloth, and frames a picture there. The light on two old tenements fills his frame, and so does the sexy sprawled Guess girl. He emerges from under his blanket and sighs. “It would make a good picture, a little overdetermined, but true enough: Do you put her in, or stay on the Path?”

The Friends of the High Line often say that they would like to see it become a promenade plantée, a long snaking viaduct with flowers, like the one, in Paris, that runs from the Bastille out to the Bois de Vincennes. The difference, evident to anyone who has walked both, is that the promenade plantée is a piece of Paris that happens to be about Paris— an elegant flowered walkway looking down on elegant flowered streets—- while the High Line is a place where the discordant encounters of its city are briefly resolved. If it is saved, it may become in reality what the real estate lawyers, of all improbably poetic people, have always known it was. An easement in the air.